International/ News/ Top Stories

Trump Immigration Policy Sparks Fear in LGBT Folks in El Salvador

“Everyone has delayed their plans to travel (to the U.S.) because they are afraid of being detained,” he told the Washington Blade.

El Salvador has one of the world’s highest per capita murder rates because of violence that is frequently associated with MS-13, 18th Street and other street gangs. Pacheco and other advocates with whom the Blade spoke this month said this violence is among the main reasons that prompt LGBTI Salvadorans to leave the country.

Ever Pacheco, director of Colectivo LGBTI Estrellas del Golfo, an LGBTI advocacy group in La Unión, El Salvador, and his colleague Valeria at their offices on July 14, 2018. (Washington Blade photo by Michael K. Lavers)

‘People aren’t going to the U.S. because it’s cold’

Pacheco said six transgender people from La Unión have migrated to the U.S. in recent years “because of the situation in the country with the gangs.” He told the Blade that discrimination and a lack of economic opportunities because of their gender identity also factored into their decisions to leave El Salvador.

Karla Guevara, president of Colectivo Alejandría, a San Salvador-based advocacy group, pointed out to the Blade last year that 18 trans women were known to have been killed in El Salvador in 2015. Francela Méndez, a Colectivo Alejandría board member, on May 31, 2015, became one of these statistics when she was murdered at a friend’s home in Sonsonate Department, which is about an hour west of San Salvador.

Three trans women were killed in February 2017 in San Luis Talpa, a city that is near El Salvador’s main international airport. Karla Avelar, a prominent activist who the Blade interviewed in San Salvador last September, asked for asylum in Ireland after she and her mother received threats.

“People are not going to the U.S. because it’s cold,” said Andrea Ayala, executive director of Espacio de Mujeres Lesbianas por la Diversidad, an advocacy group known by the acronym ESMULES, as she spoke with the Blade at a San Salvador coffee shop on July 13. “People are not going (to the U.S.) because it’s so beautiful.”

“People migrate because they will die and because they are hungry and because they are in need,” she added.

William Hernández, chief executive officer of Asociación Entre Amigos LGBTI de El Salvador, another Salvadoran advocacy group, echoed Ayala.

Hernández told the Blade on July 13 during an interview at a San Salvador hotel that is less than a mile from the U.S. Embassy that the violence in El Salvador is “worse” now than it was during the country’s civil war from 1979-1992.

He said some gangs target trans people and “obviously gay men.” Hernández also told the Blade the only time residents of one neighborhood that is controlled by two rival gangs can cross the street “without suffering the consequences for the act of crossing the street” is when they need to take public transportation.

“This is the reality in general,” he said.

Salvadoran government urged to forcefully criticize Trump

The Trump administration’s decision earlier this year to end the Temporary Protected Status program for the up to 200,000 Salvadorans who have received temporary residency permits that allow them to stay in the U.S. sparked widespread outrage among immigrant rights advocates.

Ayala and Ámbar Alfaro of ASPIDH Arcoiris Trans, a San Salvador-based trans advocacy group, are among those who criticized the White House’s decision. Pacheco’s mother is a TPS recipient who has lived in Houston for 15 years.

“The impact that it has had has been very clear,” Pacheco told the Blade, referring to the end of TPS for Salvadorans.

The Salvadoran government in January condemned Trump after he reportedly described El Salvador as a “shithole” country. Ayala and Hernández both accused President Salvador Sánchez Cerén of not doing enough to challenge the White House over its immigration policy, which includes the continued separation of migrant children from their families.

“It (the Salvadoran government) has a close relationship with the Trump administration, at the very least, for money,” said Pacheco.

The U.S. Agency for International Aid on its website notes El Salvador received $74,831,935 in U.S. foreign aid in fiscal year 2016. Remittances, which primarily come from Salvadorans who live in the U.S., accounts for nearly a fifth of El Salvador’s GDP.

Hernández said there is a “lack of leadership” from Sánchez Cerén on a host of issues that include health care, LGBTI rights and abortion. Hernández also noted U.S. Ambassador to El Salvador Jean Manes has been “very serious” in criticizing the government’s efforts to reduce gang violence and fight corruption.

“The United States government cannot tell us what to do, but it’s also what are we going to do,” said Hernández. “The honorable ambassador has a very rigid position, but also one of a lot of cooperation.”

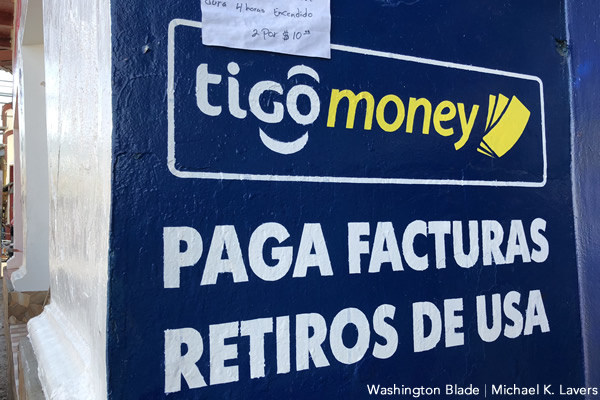

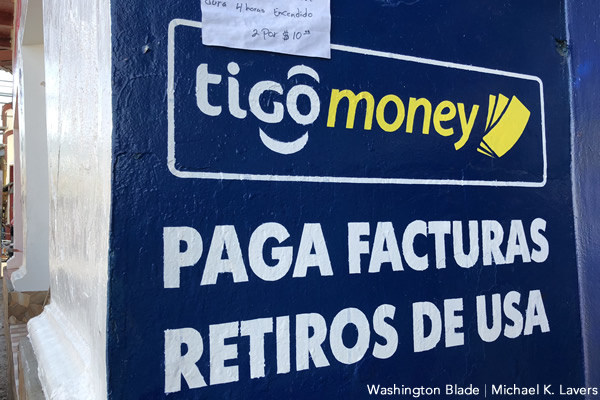

A store in La Unión, El Salvador, allows customers to receive remittances from the U.S. Salvadoran government figures indicate remittances account for nearly a fifth of the country’s total economy. (Washington Blade photo by Michael K. Lavers)

Group provides information, assistance to LGBTI migrants

Asociación Entre Amigos LGBTI de El Salvador has created an online initiative that seeks to provide information to migrants about where they can seek assistance as they travel from El Salvador to the U.S.-Mexico border. Hernández nevertheless told the Blade that neither he nor his organization encourages LGBTI Salvadorans to leave the country without documents.

“We encourage people not to migrate illegally or undocumented,” he said. “But we know that many times they leave the country with only minutes to spare. So, what we are doing is getting the word out about the safest way to go and how they can receive support along the way.”

A store in La Unión, El Salvador, allows customers to receive remittances from the U.S. Salvadoran government figures indicate remittances account for nearly a fifth of the country’s total economy. (Washington Blade photo by Michael K. Lavers)

Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen earlier this month met with the foreign ministers of El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala and Mexico in Guatemala City. She announced the creation of an office within her agency that will advise their governments about the reunification of migrant children who have been separated from their parents.The Trump administration on June 19 withdrew the U.S. from the U.N. Human Rights Council. U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein the day before condemned the separation of young migrant children from their parents along the U.S.-Mexico border.

Ayala told the Blade the Trump administration’s decision to withdraw the U.S. from the U.N. Human Rights Council was an attempt to deflect attention away from its immigration policy. She also spoke directly to Americans who continue to support it.

“I invite them to reflect with respect to the pain that this figure is inflicting on not only people from his country,” Ayala told the Blade.

ESMULES Executive Director Andrea Ayala in San Salvador, El Salvador, on Sept. 25, 2017. (Washington Blade photo by Michael K. Lavers)

She noted the U.S. provided military aid to the Salvadoran government during the civil war.Salvadoran immigrants who fled the war formed MS-13 in Los Angeles in the 1980s. Gang members who have been deported to El Salvador over the last two decades have been linked to murders and other acts of violence in the country.

“(The war) left El Salvador in ruins with military dictators, with an untold number of disappeared people,” Ayala told the Blade. “We survived 12 years of armed conflict that was, in part, supported by the United States.”

She added Trump continues to use migrants as scapegoats.

“Hate is a very strong word,” said Ayala. “This hatred is the distinction of what is different.”

Ernesto Valle in San Salvador, El Salvador, contributed to this article.