Photographer Alice Austen was the queer star of the Gilded Age

Alice Austen, far left, and other members of The Darned Club on Oct. 29, 1891.Courtesy Collection of Alice Austen House

Born into Victorian tradition in 1866, Alice Austen enjoyed a position in Staten Island society that gave her freedom to pursue what she dubbed “the larky life,” a whirlwind of fashionable gatherings and mischief that challenged social norms. But it was the gift of a wooden box camera from her uncle — and a chance meeting in the Catskills — that set the course for how Austen would be remembered beyond Gilded days: as one of America’s earliest and most adventurous women photographers and for her relationship with Gertrude Tate, which spanned more than half a century.

Though her father abandoned her mother when she was an infant, Austen enjoyed a luxurious lifestyle with extended family in their home called Clear Comfort, overlooking the coastline of the New York City borough of Staten Island. She perfected imagery of her natural surroundings, social doings and “the sporting society set” in a darkroom fashioned from a closet. Her photos serve as a portal to the Gilded Age, with images of the annual regatta, boathouse bathers, charity balls and lawn tennis, a sport newly open to women who were too restricted by corsets to actually run for the ball.

When cycling took off, so did Austen, similarly constrained by long skirts that could catch in the spokes; even so, with heavy camera equipment mounted on her bicycle, she ferried to Manhattan, where she famously documented turn-of-the-century urban life, enshrining the likes of street sweepers, rag pickers, egg sellers and messengers to gelatin print — producing her 1896 “Street Types of New York” portfolio.

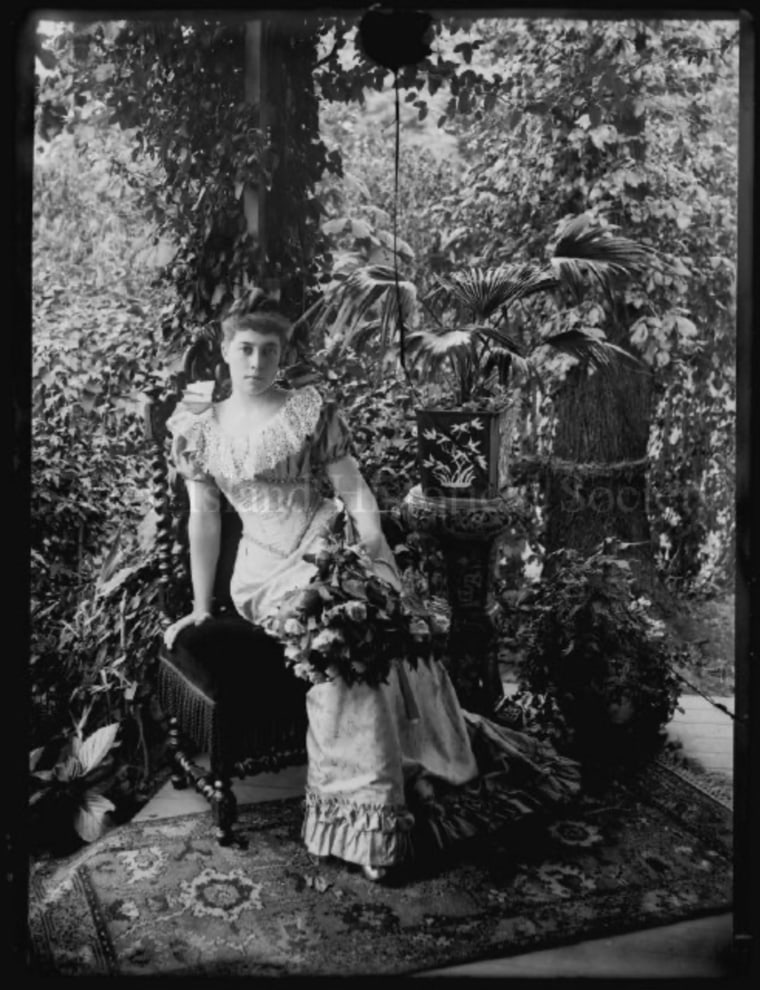

As adept at arranging portraiture as igniting flash powder over a night bloom of flowering cactus, Austen also delighted in making gender-bending exposures of female friends. Nicknamed “The Darned Club,” they posed in undergarments with cigarettes, men’s suits with fake mustaches and together in bed in Victorian nighties.

“She was in a period where she and her friends were really embracing this concept of the ‘New Woman,’” said Victoria Munro, executive director of the Alice Austen House, the original Austen residence, which also serves as a museum and exhibition space.

“She created clubs with these new activities that women were able to do, unchaperoned by men — and they were safe spaces for her and her circle of women friends who were, many of them lesbian, able to be together and have fun and really celebrate,” Munro said. “There was also a certain amount of freedom in the 1880s and 1890s, because women weren’t yet considered to even have a sexuality … so they weren’t even suspected of this kind of perceived bad behavior.”

Austen enjoyed the affections of multiple women with “decided longings in that direction,” including the amorous athlete Daisy Elliott. Elliott’s letters left little doubt about Austen’s sapphic leanings. “There is a good deal more between the lines than in them,” Elliott wrote Austen. “Read as much as you care to, and you will not be mistaken … ”

It was a romance doomed to fail, however: That same year, 1897, Austen met Tate.

Despite existing in “a very repressive, heteronormative culture,” as Munro described it, the two summered in Europe, attended the Metropolitan Opera and maintained exclusive memberships, including to the Staten Island Garden Club, which Austen founded. Tate moved in with Austen in 1917.

Bonnie Yochelson, author of “Too Good to Get Married: The Life and Photographs of Miss Alice Austen,” speculates that their social conservatism and staying close to high society in their activities were protective.

“Alice’s friends knew her for decades, and they loved her. Tate was delightful and very capable. They were accepted as a couple,” Yochelson said.

But when the 1929 stock market crash caught Austen in the crosshairs, her financial standing plummeted. Though the surrounding waterfront became industrialized, she refused to sell Clear Comfort, and she took out a mortgage not for daily expenses, but to holiday with Tate. Austen sold family heirlooms, and Tate taught dance. Foreclosure was inevitable, though they stayed on as caretakers — opening a tea room with a view of passing ships, until the frailties of age made the enterprise unsustainable.

In 1945, Austen and Tate, then in their 70s, were evicted for good.

Remarkably, the women managed to stay on the exclusive Social Register for years.

“There’s no question that they had friends, and some of their friends did abandon them as they fell on hard times,” Yochelson said. “But many people were very loyal to them … and they continued to pay their membership at a time when they were sufficiently poor that they couldn’t necessarily pay their electric bill.”

Austen sold her last remaining possessions to a junk dealer for $600. A preservationist at heart, she gave thousands of plates, negatives and personal treasures to an acquaintance, Loring McMillen, director of the Staten Island Historical Society (now Historic Richmond Town), who declared the women “not broken in spirit but broken in health and finance.”

Austen and Tate lived together in a small apartment until Austen’s arthritis proved too debilitating. When they were forced to separate, Tate moved to her sister’s home in Queens, New York, and Austen to a home for the aged — and eventually, at age 84, a literal poor farm. Ever devoted, Tate visited Austen regularly at the Staten Island Farm Colony.

But the 7,500 photos and negatives Austen entrusted to the Historical Society would prove a saving grace, and they would ensure her place as an eminent documentarian of a changing landscape in the immigration era.

In 1950, a Life magazine editor came upon Austen’s photos of 19th century American life — and learned she was alive. Life ran a story the following year, and Austen got a fee that allowed her to take up residence with a private caregiver.

Weeks after publication, the Staten Island Historical Society hosted “Alice Austen Day.” Overwhelmed and delighted to see the first public showing of her work at age 85, Austen attended with Tate and 300 guests. “I’d be taking these pictures myself if I were 100 years younger,” Austen quipped.

In June, because of Austen’s worsening condition and a bureaucratic glitch, plans were being set in motion to move her to Welfare Island, then a location of public institutions for the aged and infirm. She would not make the journey. On June 9, 1952, Tate was preparing to make the trip from Queens to visit when the phone rang: Austen had been wheeled to the nursing home porch and simply passed away, quietly bathed in morning sunlight.

Austen was buried at Staten Island’s Moravian Cemetery. Tate died 10 years later, at 91. Her family denied her wish to be buried with Austen.

The couple could not have foreseen that across the decades and into a new millennium, future strangers would be moved to advocate for recognition of their devotion: from a 1994 Lesbian Avengers protest against institutional resistance to naming the pair as more than “friends” to Munro’s mission to ensure Tate’s name is discoverable in archival metadata, given a name beyond “unknown woman.”

Their story is housed within the clapboard and stone of their historic residence, now the Alice Austen House and a nationally designated site of LGBTQ history. Today, a visitor enters to find Tate’s portrait in her rightful place in family tree documentation on the wall.

“It is imperative that we center her queerness and her identity and that we celebrate this beautiful, beautiful love story,” Munro said. “People have now come back and visited the Alice Austen House and wept because they’re so happy to see this visibility.”