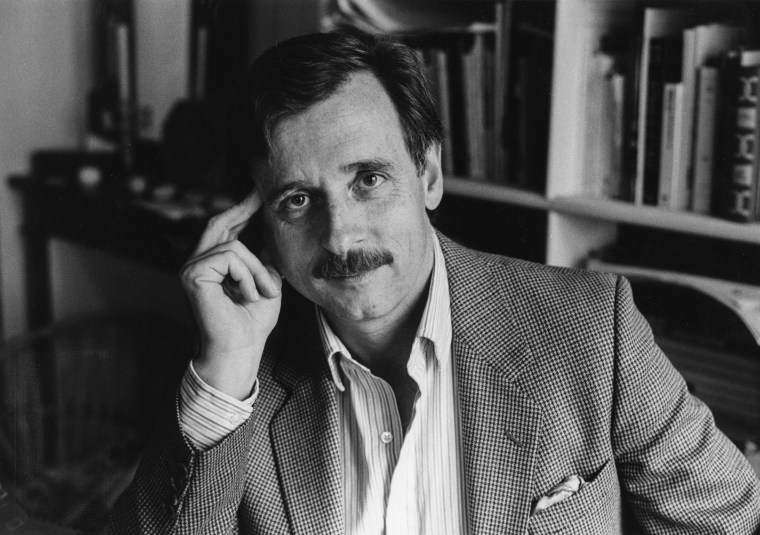

Edmund White, a groundbreaking gay author, dies at 85

Edmund White, the groundbreaking man of letters who documented and imagined the gay revolution through journalism, essays, plays and such novels as “A Boy’s Own Story” and “The Beautiful Room is Empty,” has died. He was 85.

White’s death was confirmed Wednesday by his agent, Bill Clegg, who did not immediately provide additional details.

Along with Larry Kramer, Armistead Maupin and others, White was among a generation of gay writers who in the 1970s became bards for a community no longer afraid to declare its existence. He was present at the Stonewall raids of 1969, when arrests at a club in Greenwich Village led to the birth of the modern gay movement, and for decades was a participant and observer through the tragedy of AIDS, the advance of gay rights and culture and the backlash of recent years.

A resident of New York and Paris for much of his adult life, he was a novelist, journalist, biographer, playwright, activist, teacher and memoirist. “A Boy’s Own Story” was a bestseller and classic coming-of-age novel that demonstrated gay literature’s commercial appeal. He wrote a prizewinning biography of playwright Jean Genet and books on Marcel Proust and Arthur Rimbaud. He was a professor of creative writing at Princeton University, where colleagues included Toni Morrison and his close friend, Joyce Carol Oates. He was an encyclopedic reader who absorbed literature worldwide while returning yearly to such favorites as Tolstoy’s “Anna Karenina” and Henry Green’s “Nothing.”

“Among gay writers of his generation, Edmund White has emerged as the most versatile man of letters,” cultural critic Morris Dickstein wrote in The New York Times in 1995. “A cosmopolitan writer with a deep sense of tradition, he has bridged the gap between gay subcultures and a broader literary audience.”

The age of AIDS, and beyond

In early 1982, just as the public was learning about AIDS, White was among the founders of Gay Men’s Health Crisis, which advocated AIDS prevention and education. The author himself would learn that he was HIV-positive in 1985, and would remember friends afraid to be kissed by him, even on the cheek, and parents who didn’t want him to touch their babies.

White survived, but watched countless peers and loved ones suffer agonizing deaths. Out of the seven gay men, including White, who formed the influential writing group the Violet Quill, four died of complications from AIDS. As White wrote in his elegiac novel “The Farewell Symphony,” the story followed a shocking arc: “Oppressed in the fifties, freed in the sixties, exalted in the seventies and wiped out in the eighties.”

But in the 1990s and after he lived to see gay people granted the right to marry and serve in the military, to see gay-themed books taught in schools and to see gay writers so widely published that they no longer needed to write about gay lives.

“We’re in this post-gay period where you can announce to everybody that you yourself are gay, and you can write books in which there are gay characters, but you don’t need to write exclusively about that,” he said in a Salon interview in 2009. “Your characters don’t need to inhabit a ghetto any more than you do. A straight writer can write a gay novel and not worry about it, and a gay novelist can write about straight people.”

In 2019, White received a National Book Award medal for lifetime achievement, an honor previously given to Morrison and Philip Roth among others.

“To go from the most maligned to a highly lauded writer in a half-century is astonishing,” White said during his acceptance speech.

Childhood yearnings

White was born in Cincinnati in 1940, but age at 7 moved with his mother to the Chicago area after his parents divorced. His father was a civil engineer “who reigned in silence over dinner as he studied his paper.” His mother a psychologist “given to rages or fits of weeping.” Trapped in “the closed, sniveling, resentful world of childhood,” at times suicidal, White was at the same time a “fierce little autodidact” who sought escape through the stories of others, whether Thomas Mann’s “Death in Venice” or a biography of the dancer Vaslav Nijinsky.

“As a young teenager I looked desperately for things to read that might excite me or assure me I wasn’t the only one, that might confirm my identity I was unhappily piecing together,” he wrote in the essay “Out of the Closet, On to the Bookshelf,” published in 1991.

As he wrote in “A Boy’s Own Story,” he knew as a child that he was attracted to boys, but for years was convinced he must change — out of a desire to please his father (whom he otherwise despised) and a wish to be “normal.” Even as he secretly wrote a “coming out” novel while a teenager, he insisted on seeing a therapist and begged to be sent to boarding school. One of the funniest and saddest episodes from “A Boy’s Own Story” told of a brief crush he had on a teenage girl, ended by a polite and devastating note of rejection.

“For the next few months I grieved,” White writes. “I would stay up all night crying and playing records and writing sonnets to Helen. What was I crying for?”

He had a whirling, airborne imagination and New York and Paris had been in his dreams well before he lived in either place. After graduating from the University of Michigan, where he majored in Chinese, he moved to New York in the early 1960s and worked for years as a writer for Time-Life Books and an editor for The Saturday Review. He would interview Tennessee Williams and Truman Capote among others, and, for some assignments, was joined by photographer Robert Mapplethorpe.

Socially, he met Burroughs, Jasper Johns, Christopher Isherwood and John Ashbery. He remembered drinking espresso with an ambitious singer named Naomi Cohen, whom the world would soon know as “Mama Cass” of the Mamas and Papas. He feuded with Kramer, Gore Vidal and Susan Sontag, an early supporter who withdrew a blurb for “A Boy’s Own Story” after he caricatured her in the novel “Caracole.”

“In all my years of therapy I never got to the bottom of my impulse toward treachery, especially toward people who’d helped me and befriended me,” he later wrote.

Early struggles, changing times

Through much of the 1960s, he was writing novels that were rejected or never finished. Late at night, he would “dress as a hippie, and head out for the bars.” A favorite stop was the Stonewall, where he would down vodka tonics and try to find the nerve to ask a man he had crush on to dance. He was in the neighborhood on the night of June 28, 1969, when police raided the Stonewall and “all hell broke loose.”

“Up until that moment we had all thought homosexuality was a medical term,” wrote White, who soon joined the protests. “Suddenly we saw that we could be a minority group — with rights, a culture, an agenda.”

Before the 1970s, few novels about openly gay characters existed beyond Vidal’s “The City and the Pillar” and James Baldwin’s “Giovanni’s Room.” Classics such as William Burroughs’ “Naked Lunch” had “rendered gay life as exotic, marginal, even monstrous,” according to White. But the world was changing, and publishing was catching up, releasing fiction by White, Kramer, Andrew Holleran and others.

White’s debut novel, the surreal and suggestive “Forgetting Elena,” was published in 1973. He collaborated with Charles Silverstein on “The Joy of Gay Sex,” a follow-up to the bestselling “The Joy of Sex” that was updated after the emergence of AIDS. In 1978, his first openly gay novel, “Nocturnes for the King of Naples,” was released and he followed with the nonfiction “States of Desire,” his attempt to show “the varieties of gay experience and also to suggest the enormous range of gay life to straight and gay people — to show that gays aren’t just hairdressers, they’re also petroleum engineers and ranchers and short-order cooks.”

With “A Boy’s Own Story,” published in 1982, he began an autobiographical trilogy that continued with “The Beautiful Room is Empty” and “The Farewell Symphony,” some of the most sexually direct and explicit fiction to land on literary shelves. Heterosexuals, he wrote in “The Farewell Symphony,” could “afford elusiveness.” But gays, “easily spooked,” could not “risk feigning rejection.”

His other works included “Skinned Alive: Stories” and the novel “A Previous Life,” in which he turns himself into a fictional character and imagines himself long forgotten after his death. In 2009, he published “City Boy,” a memoir of New York in the 1960s and ’70s in which he told of his friendships and rivalries and gave the real names of fictional characters from his earlier novels. Other recent books included the novels “Jack Holmes & His Friend” and “Our Young Man” and the memoir “Inside a Pearl: My Years in Paris.”

“From an early age I had the idea that writing was truth-telling,” he told The Guardian around the time “Jack Holmes” was released. “It’s on the record. Everybody can see it. Maybe it goes back to the sacred origins of literature — the holy book. There’s nothing holy about it for me, but it should be serious and it should be totally transparent.”