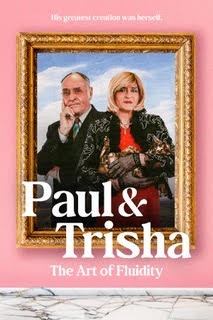

“Paul & Trisha: The Art of Fluidity” — Colorful, Exceptional Documentary Arrives on VOD, Digital July 9 from Gravitas Ventures

Director/producer Fia Perera‘s Perera Pictures is proud to announce the North American video-on-demand (VOD) release of “Paul & Trisha: The Art of Fluidity” (Gravitas Ventures) on July 9, 2024. This colorful, heartwarming, and truly inspirational documentary, which

explores the lives of two renowned British artists who exist in one gender-fluid body: Paul Whitehead and Trisha Van Cleef, is Perera’s directorial debut, and will stream in the U.S., Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Pre-orders are available now on iTunes/Apple TV.

“A brilliant, beautiful, sensitive documentary” (Broadway to Vegas), “Paul & Trisha: The Art of Fluidity” has received rave reviews, with critics focusing on how Perera “reveals the challenges and joyful moment which both souls celebrate and endure…with great dignity and purpose” (Film Threat), while others praise the film’s style, exclaiming “the artwork alone is worth the price of admission, but the story is amazing and its presentation is brilliant” (Splash Magazine).

“As a filmmaker and activist, my passion is spotlighting and elevating individuals like Paul and Trisha, who navigate their gender fluidity and duality with great freedom”, said Perera. “My mission with this film is to help inspire other people who are struggling to be their true selves to take the leap!”

“Paul & Trisha: The Art of Fluidity” focuses on Paul Whitehead, a painter, graphic designer, writer, and musician who worked as an art director for Time Out and John Lennon; founded the Eyes and Ears Foundation and its Artboard Festival, which allowed artists to showcase their work on billboards; and made album covers for music icons like Genesis, Credence Clearwater Revival, Van der Graaf Generator, and Peter Hammill.

Whitehead began exploring his gender identity through cross-dressing during the 1960s, leading to the emergence of the converged artist Trisha Van Cleef in 2004. The film delves into the brutal challenges and beautiful victories that Paul and Trisha have faced—together and individually—in the mercurial and competitive art world while unapologetically navigating the uncharted waters of gender identity and artistic expression, breaking down perilous stigmas along the way.

“Paul & Trisha: The Art of Fluidity” has held a successful festival run with screenings at Cinequest Film Festival, Santa Fe Film Festival Ojai Film Festival, and New Filmmakers LA Docuslate Festival.

Perera Pictures & Fisky Enterprises present “Paul & Trisha: The Art of Fluidity.” Featuring Paul Whitehead & Trisha Van Cleef, the film is written, directed and produced by Fia Perera, with Adam Fisk serving as an executive producer, with cinematography and editing by William Gilmore.