U.S. progress in HIV fight continues to trail many other rich nations

New HIV infections continue to ebb only modestly in the United States, while many other wealthy Western nations have posted steep reductions, thanks to more successful efforts overseas to promptly diagnose and treat the virus and promote the HIV prevention pill, PrEP.

In a new HIV surveillance report published Tuesday, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that new HIV transmissions declined by 12% nationally between 2017 and 2021, from 36,500 to 32,100 cases.

By comparison, according to estimates by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, between 2015 and 2021, the annual infection rate plunged by more than 70% in the Netherlands, 68% in Italy and 44% in Australia. United Kingdom health authoritiesrecorded about 2,700 diagnoses in England in 2021 — a drop of approximately one-third since 2017 and one-half since 2015.

Experts told NBC News that the U.S. remains so far behind in combating HIV because of the nation’s lack of a national health care system and sexual-health clinic network; fragmented and underfunded public health systems; and poorer synchronization between government, academia, health care and community-based organizations.

These experts also pointed to factors such as racism, inadequate adoption of evidence-based treatment for opioid use disorder, state laws criminalizing HIV exposure and medical mistrust in people of color.

“HIV in the United States is very much a disease of those who are most disenfranchised in society,” Dr. Boghuma Titanji, an infectious disease specialist at Emory University, said.

The power of the pills

The 2010s heralded the era of so-called biomedical HIV prevention. A series of landmark studies established two critical facts: one, that fully suppressing the virus with antiretroviral treatment eliminates sexual transmission risk in addition to extending life expectancy nearly to normal, and two, that when HIV-negative people take the antiretrovirals Truvada or Descovy daily as pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, they reduce their risk of contracting the virus by 99% or more.

Accordingly, the nations that have succeeded in far besting the U.S. in reducing new infections have gotten more people with HIV diagnosed and on treatment, and have done so sooner in the course of infection. These countries have also often seen a greater proportion of those at the highest risk of HIV, namely gay men, get on PrEP.

An estimated 1.2 million Americans have HIV. According to the CDC, only 87% of them are diagnosed and just 58% are in treatment and have a fully suppressed viral load. This latter figure compares with robust national viral suppression rates, estimated by health authorities, of 82% in Australia, 83% in the Netherlands, 89% in the U.K and 74% in Italy. The rate is higher than 70% in at least 16 other European nations.

In the U.S., the virus has maintained its vastly disproportionate impact on gay and bisexual men, who, according to the new CDC report, comprise about 70% of new cases despite making up only about 2% of the adult population.

First approved in 2012, PrEP has soared in popularity among white gay men in the U.S., while failing to gain a major foothold among their Black and Latino peers.

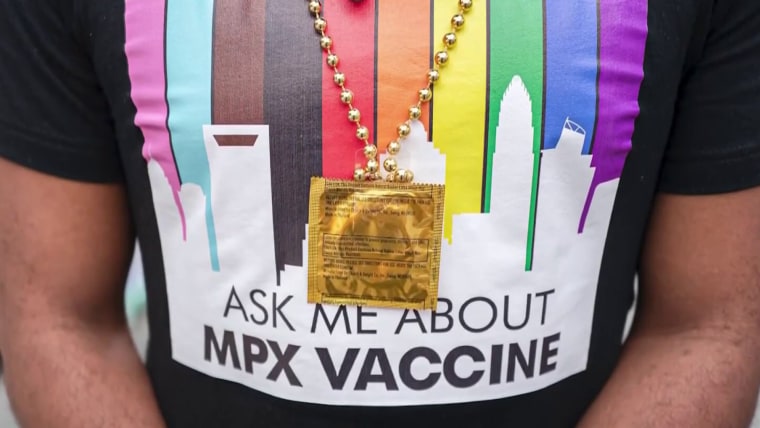

The CDC has estimated that about 814,000 gay and bisexual men are good PrEP candidates. Recent data suggested that the number of people, overwhelmingly from this population, who have ever used PrEP each year more than doubled between 2017 and 2022, to at least 318,400. However, a recent CDC study suggested that only about half that group took PrEP during any one month last year, suggesting that many people take it only temporarily.

The most recent four-year national decline was driven by an estimated one-third drop in cases among 13- to 24-year-olds, which Dr. Robyn Neblett Fanfair, acting director of the CDC’s Division of HIV Prevention, characterized as “very encouraging” on a Tuesday media call. The CDC attributes this success to progress in expanding testing, treatment and PrEP among gay and bisexual males, who comprised 80% of the cases in that age group.

But infection rates among these men’s older counterparts have remained statistically stable.

In England, vastly improved biomedical prevention among gay and bisexual men slashed their HIV diagnosis rate so drastically — by about three-quarters in a decade — that in 2022, fewer of them tested positive for the virus than heterosexuals. In the U.S., gay and bisexual men’s transmissions outnumber heterosexuals’ by more than three to one.

Dr. Chris Beyrer, director of the Duke University Global Health Institute, remarked that many of the nations that have seen such precipitous declines “don’t have to deal with the really sharp health disparities and lack of access” that have colored the U.S. HIV fight.

Persistent divides

HIV has for decades exposed racial and socioeconomic fault lines in the U.S., with the virus disproportionately affecting people of color and the poor.

Blacks and Latinos comprised a respective 40% and 29% of the most recent transmissions, despite these racial groups making up only 12% and 19% of the U.S. population. Approximately one in five new infections are among women, more than half of them among Black women.

The new CDC report reveals that such racial disparities have abated only slightly in recent years. Breaking down the transmission trajectory by race and sex showed that Black men were the only group to see a statistically significant reduction.

Estimated new infections among gay and bisexual men declined between 2017 and 2021 from 9,300 to 8,100 among Blacks and 7,800 to 7,200 among Latinos. However, these changes were not statistically significant, in contrast to the significant decline among whites, from 5,800 to 4,800 cases.

Politics and public health

Conservative politicians’ recent fervent use of anti-LGBTQ legislation and rhetoric to appeal to the Republican base threatens to further undermine efforts to combat HIV, public health experts warned.

Recommended

OUT POLITICS AND POLICYMontana first to ban drag performers from reading to children in schools, libraries

BUSINESS NEWSTarget pulls some Pride collection items after threats to employees

“All of this plain hatred at the LGBTQ community is not good for ending the epidemic,” Kathie Hiers, CEO of AIDS Alabama, said.

Hiers also decried what she characterized as insufficient and poorly coordinated national support for housing among those living with and at risk for HIV. She pointed to the robust support New York provides HIV-positive homeless people as a pillar of that state’s success in fighting the virus.

About half of HIV transmissions occur in the South, which has an infection rate approximately 50% higher than in the West and Northeast, and double that of the Midwest. Southern states, dominated by Republicans, have tended to devote fewer resources to combatting the virus compared with liberal states, and cities elsewhere, such as San Francisco and New York, that have a history of beating back substantial HIV epidemics.

Experts have long cited the refusal of most Southern legislatures to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act as a major driver of regional disparities in HIV treatment and prevention.

“Medicaid expansion is a massive structural intervention to support the most vulnerable in our communities,” said Dr. Hyman Scott, an HIV prevention expert at the San Francisco Department of Public Health.

Silver linings

There is hope that the South may be turning a corner, given the CDC’s finding that it was the only region to see a statistically significant decline — of 12% — in estimated new HIV infections between 2017 and 2021.

Additionally, HIV’s decline appears to be accelerating, however marginally. The CDC previously reported the new infection rate was essentially stable during the mid-2010s and then inched 8% lowerbetween 2015 and 2019.

And while the most recent data are somewhat hazy due to a drop in HIV testing following Covid-19’s onset, an apparent sustained decline in transmissions in 2020 and 2021 represents a victory for the HIV treatment and prevention workforce. Infectious disease clinics, for example, often proved nimble in the face of the new pandemic’s disruptions by pivoting to telehealth and supplying patients with months of medications at a time.

The CDC isn’t satisfied.

“In prevention, patience is not a virtue,” Dr. Jonathan Mermin, director of the CDC’s National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, said during the Tuesday media call. “We can end HIV in America. We know the way, but does our nation have the will?”

Fighting for the future of HIV

The federal government is hoping that a surge in spending will be the linchpin that finally sends the HIV epidemic into a swift retreat.

In 2019, Donald Trump endorsed a plan to ratchet up federal outlays on HIV. Between the 2020 and 2023 fiscal years, this infusion of new annual funds, largely funneled to the 48 counties where about half of transmissions occur, has soared from $267 million to $573 million. Mermin called for Congress to approve President Biden’s budget request of $850 million for the 2024 fiscal year.

The expressed aim of the spending is to cause the 2017 HIV transmission rate to collapse 75% by 2025 and 90% by 2030. But as CDC surveillance quite evidently shows, the epidemic’s current trajectory is nowhere near on track to achieve such lofty goals.

Emory’s Boghuma Titanji said that to succeed in beating HIV, the nation must address the myriad intractable social inequities that drive transmission, including poverty, racism, stigma, homophobia, homelessness and poor health care access.

Absent such progress, Titanji said, she anticipates that by the decade’s end, HIV in the U.S. will be “pretty much the same: a disease that will continue to disproportionately impact the most vulnerable communities.”