What does pansexual mean, and how is it different from bisexual and polysexual?

Let’s take a moment to celebrate the pansexuals: the wonderful guys, gals and non-binary pals who love who they love regardless of gender.

Pansexuality is part of the Bisexual+ Umbrella, meaning that it’s one of many identities in which someone is attracted to more than one gender.

But how exactly do you define pansexuality, and how is it different from bisexuality or polysexuality?

What does pansexual mean?

Every pansexual’s understanding of their sexuality is personal to them, but in general it means that they aren’t limited by sex or gender when it comes to those they’re attracted to.

The word comes from the Greek word “pan,” which means “all”. But that doesn’t mean pansexuals are attracted to anybody and everybody, just as heterosexual women aren’t attracted to all men. It simply means that the people they are into might identify anywhere on the LGBT+ spectrum.

This includes people who are gender-fluid, and those who don’t identify with any gender at all (agender).

In fact, some pansexuals describe themselves as “gender-blind”, meaning that gender doesn’t play any part in their sexuality; they’re attracted purely to a person’s energy rather than any other attributes.

What’s the difference between pansexual and bisexual?

Good question! Sometimes pansexuality is used as a synonym for bisexuality, but they are subtly different.

Bisexual means being attracted to multiple genders, whereas pansexual means being attracted to all genders. Both orientations are valid in their own right and it’s up to the individual to decide which one fits them best.

Some people assume that bisexual people are erasing non-binary people or enforcing a rigid gender binary, because they believe the word bisexual implies that there are only two genders. We’re happy to inform you this isn’t the case!

The vast majority of bisexual people love and support the non-binary community, and many non-binary people are bisexuals themselves.

The reality is that bi people simply have “the potential to be attracted – romantically and/or sexually – to people of more than one sex and/or gender, not necessarily at the same time, not necessarily in the same way, and not necessarily to the same degree,” as advocate Robyn Ochs describes.

What’s the difference between pansexual and polysexual?

The word polysexual comes from the Greek prefix “poly“ meaning “many”, and the term has been around since the 1920s or 30s, if not earlier.

There’s some overlap between pansexual and polysexual, as both appear under the Bisexual+ Umbrella. The key difference is that someone identifying as polysexual is not necessarily attracted to all genders, but many genders.

A good analogy to describe it is how you feel about your favourite colours: a pansexual person might like every colour of the rainbow, whereas a polysexual person might say they like all the colours except blue and green.

But more often than not, those who identify as polysexual tend to ignore gender binaries altogether, especially when it comes to who they are and aren’t attracted to.

It’s worth noting that polysexuality also has nothing to do with polyamory, which is style of consensual relationship, not a sexuality.

What pansexual celebrities are there?

Pansexuality has been around for as long as humans have, but the term is becoming more mainstream as more celebrities publicly identify as pansexual themselves.

Just a few of the big pansexual names out there are Lizzo, Cara Delevigne, Miley Cyrus, Janelle Monae, Angel Haze, Jazz Jennings, Brendan Urie, Yungblud, Nico Tortorella, Courtney Act, Bella Thorne, Joe Lycett, Tess Holliday and Christine and the Queens.

And as of 2020, the UK now has its first out pansexual MP: the Lib Dem Layla Moran.

“Pansexuality, to me, means it doesn’t matter about the physical attributions of the person you fall in love with, it’s about the person themselves,” she told PinkNews.

“It doesn’t matter if they’re a man or a woman or gender non-conforming, it doesn’t matter if they identify as gay or not. In the end, these are all things that don’t matter – the thing that matters is the person, and that you love the person.”

What does the pansexual Pride flag look like?

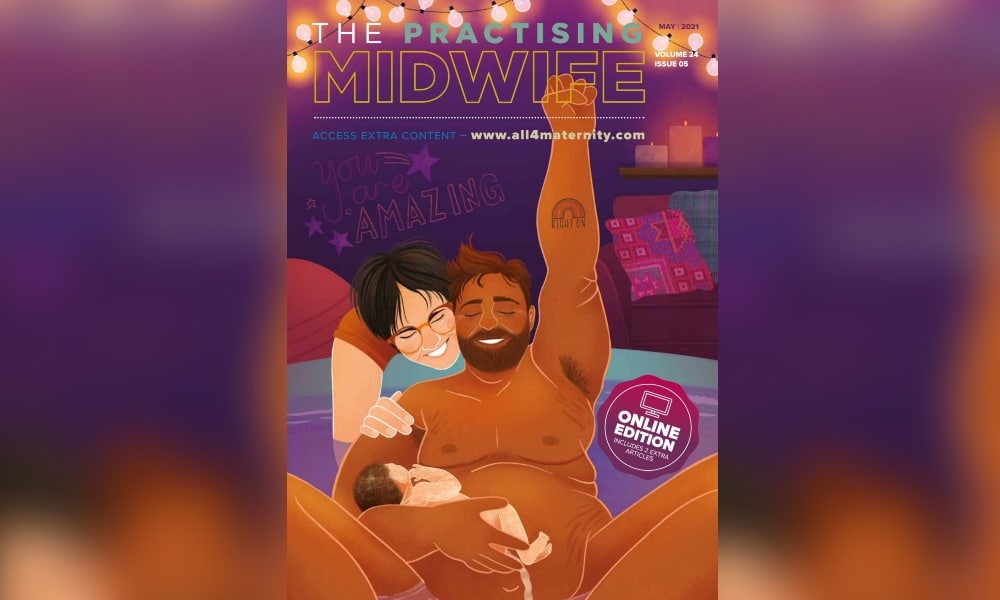

We’re glad you asked. It looks like this:

When is pansexual Pride day?

Pansexual & Panromantic Awareness Day falls on 24 May. It’s a day to celebrate the pan community and educate others on what it means – so you can start by telling your friends it’s got absolutely nothing to do with saucepans.