‘Everywhere Is Queer’: New worldwide map highlights LGBTQ-owned businesses

Charlie Sprinkman traveled to 42 of the 50 states for work as a representative of an organic beverage company in 2019 and kept Googling “queer hangouts here” when he would arrive in a new town. But he would often come up empty.

“I couldn’t find a resource for it,” Sprinkman, 25, said of a centralized directory of LGBTQ-owned businesses.

Then, in the summer of 2021, he was a counselor at a queer leadership camp for 12- to 18-year-olds outside Los Angeles, and he said being surrounded by 100 LGBTQ people for 11 days was “euphoric.”

“I was like, ‘How do I create this space?’ Maybe not as grand as a camp, but like a space where people can feel this energy and not be judged for who they are,” said Sprinkman, who currently lives in Bend, Oregon, and works in customer service.

On the long drive back from the camp to his then-home in Colorado, Sprinkman said the phrase “Everywhere is queer” came to his mind. A few months later, in January of this year, it became the name of his LLC.

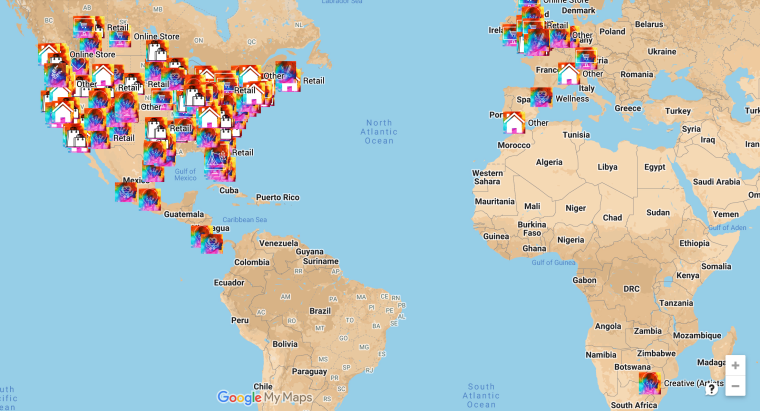

Everywhere Is Queer consists of both a website that houses a worldwide map of LGBTQ-owned businesses and an Instagram page that shines a spotlight on some of these companies. Three months after the launch, the map has more than 500 businesses listed, and the Instagram page has nearly 5,000 followers.

Businesses include retailers like Housewife Skateboards in Los Angeles, coffee shops like Lussi Brown Coffee Bar in Lexington, Kentucky, and lodging like Hotel Perruquet in the Italian Alps.

Sprinkman said the project is personal for him, not just as a queer traveler but as someone who didn’t know of any LGBTQ-friendly spaces in his small suburban hometown about 30 miles west of Milwaukee.

“I didn’t have any out cousins, aunts, uncles, anyone as like an influence, so I didn’t really have a space as a child to find queer spaces around my hometown,” he said. “As I was building Everywhere Is Queer, I was thinking about youth, my hometown, trying to find and build spaces for them to just, even if they’re not out, just sit in a queer-owned coffee shop and just see queer people. You know, that subconscious layer of just like seeing queer people is what I hope Everywhere Is Queer will provide for so many.”

So far, Sprinkman said most of the LGBTQ-owned businesses on the map are concentrated in the U.S., and that there are only four states that don’t have an LGBTQ-owned business listed yet. He said there are also businesses listed in Germany, Spain, South Africa, the United Kingdom, Costa Rica and Mexico.

Anyone can add a business to the map by going to Everywhere Is Queer’s websiteand filling out an online form.

One business owner listed on the map said she has seen more queer people come into her restaurants. Mel McMillan is the owner of Sammich in Oregon, which sells sandwiches made with house-smoked meats. Both of her Sammich locations, in Portland and Ashland, are listed on the map, as is her food truck, also in Portland.

“If you Google ‘lesbian meat maker,’ you’ll get a real touch of what’s going on with me,” McMillan said. (It’s true: An article about her is the first thing that comes up in the search results for that phrase.)

Get the Morning Rundown

Get a head start on the morning’s top stories.SIGN UPTHIS SITE IS PROTECTED BY RECAPTCHA PRIVACY POLICY | TERMS OF SERVICE

McMillan, 39, said that one of the things she loves about Everywhere Is Queer is that it’s bringing together queer people from different generations.

Last month, Sprinkman and McMillan invited about 20 people to Sammich’s Portland location.

“The first thing that I thought was so cool about this was it’s bridging the gap between older queers and younger queers,” McMillan said. “That was really cool, because there were 20-somethings and 40-somethings, and there’s not even a place really for that either.”

Recommended

OUT NEWSGay parents called ‘rapists’ and ‘pedophiles’ in Amtrak incident

OUT NEWSGay couple files complaint against New York City over denying IVF coverage

Sprinkman said he’s also building a job board that allows businesses that are on the map to share job opportunities.

“I also have been searching for a queer-owned business job board, and I cannot find one, so we’re building one,” he said.

In the future, he said, he hopes to build an app to house the map and travel around to visit many of the LGBTQ-owned places listed.

“I would love to hit the road and visit and really hear the authentic stories of these queer-owned businesses,” he said, adding that “uplifting” the voices of queer business owners is a dream of his.

He said he also hopes that it helps LGBTQ travelers feel safer — and some have told him that it already has. He’s received hundreds of messages from people who have thanked him for filling a void.

States across the U.S. have a variety of laws regarding whether businesses can refuse service to LGBTQ people. Twenty-one states and Washington, D.C., have laws that explicitly prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity in public accommodations, such as businesses, according to the Movement Advancement Project, a nonprofit think tank. Eight states interpret their laws to protect LGBTQ people or provide partial protection. The remaining 21 states and five territories don’t provide any protection based on LGBTQ status.

As of this month, the map has been viewed more than 100,000 times, and Sprinkman doesn’t make any money off it.

“I’m building this just out of my own little queer heart,” he said.

He hopes that the map can ultimately just help people find the spaces that allow them to be themselves.

“I hope that a queer-owned business that was maybe unknown before can provide a space and a little bit more confidence, less judgment for anyone that’s struggling with figuring out their most authentic self,” Sprinkman said. “We’re always constantly on a journey, all of us.”