In the last leg of what has been a heated midterm election cycle, some conservative groups have ramped up misleading or inflammatory campaign ads targeting transgender rights, which have become an increasingly partisan and divisive issue.

A radio ad from America First Legal, a conservative group founded by Stephen Miller, who served as a top adviser to former President Donald Trump, accused President Joe Biden and “progressive leaders” of pushing children to take hormones and undergo surgery “to remove their breasts and genitals.”

“Not long ago, everyone knew that you’re either born a boy or a girl,” the narrator says over ominous music. “Not anymore. The Biden administration’s pushing radical gender experiments on children.”

America First Legal did not respond to NBC News’ request for comment.

Within the last several weeks, the American Principles Project aired campaign ads in six battleground states, the group wrote on Twitter. One of the TV ads, which it released in Arizona, accuses Sen. Mark Kelly, an Arizona Democrat, and President Biden of “pushing dangerous transgender drugs and surgeries on kids — taking away parental rights.” Simultaneously, the group launched an ad in Wisconsin accusing Democratic candidates of supporting legislation “that would destroy girls’ sports.”

https://iframe.nbcnews.com/ss4Cn2T?_showcaption=true&app=1

Terry Schilling, president of American Principles Project PAC, told NBC News that the “explosion of gender ideology” is “one of the biggest threats” to American families.

“Our goal with our ads is to ensure American voters across the political spectrum understand what’s really happening on these issues (despite the media gaslighting) and that Democrats like Joe Biden and his allies are responsible for it,” he said in an email.

Citizens for Sanity, another group formed by former Trump administration advisers, has released ads addressing immigration, criminal justice, gender identity and other issues in such battleground states as Nevada, Arizona and Georgia. One of its ads accuses Biden and Democrats of telling children “boys are girls and girls are boys” and promoting “surgery to remove body parts.”

https://iframe.nbcnews.com/pUIYTGJ?_showcaption=true&app=1

Citizens for Sanity did not respond to NBC News’ request for comment.

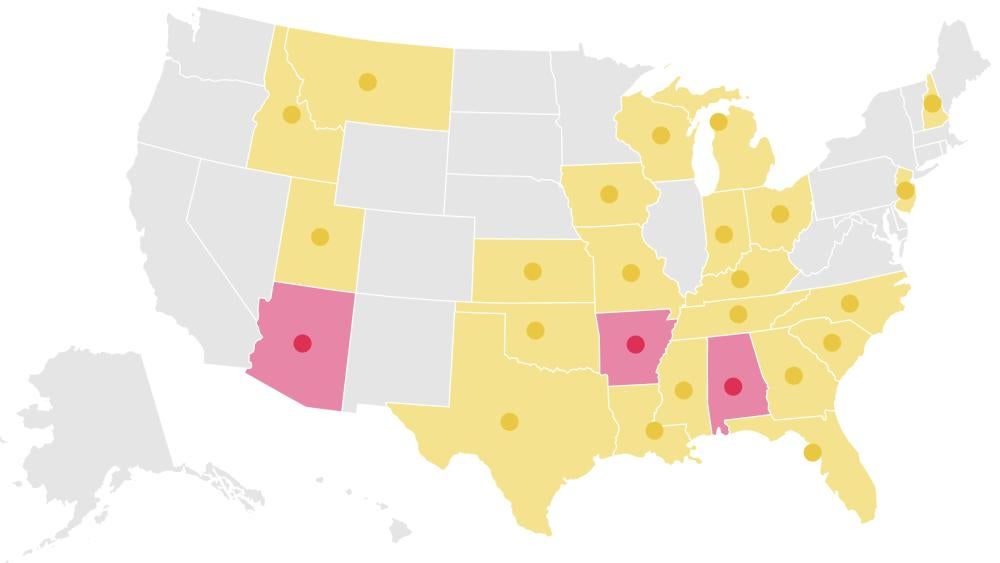

The Human Rights Campaign, the country’s largest LGBTQ advocacy group, estimates these groups have spent at least $50 million on such ads across at least 25 states, though NBC News could not independently confirm this finding.

https://iframe.nbcnews.com/AtBiZcr?_showcaption=true&app=1

Transgender advocates have slammed the advertisements as misleading and dangerous, and have pointed to the medical community’s support of gender-affirming care for trans youths.

Major medical associations, including the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Psychological Association, have supported such care for transgender minors. In a June 2021 statement, the American Medical Association reinforced its opposition to restrictions on transgender medical care and denounced “governmental intrusion into the practice of medicine that is detrimental to the health of transgender and gender-diverse children and adults.”

Adolescents generally cannot receive gender-affirming surgery until they are 18, but in rare circumstances some surgeons may perform a double mastectomy, also known as top surgery, on teens under 18 “who are able to fully understand the risks and benefits,” according to the Endocrine Society. The effects of a more common treatment for transgender minors, puberty blockers, are reversible, the society says.

Justin Unga, the director of strategic initiatives for the Human Rights Campaign, said ads targeting transgender rights can have real-world ramifications.

“The lies that they’re telling really illustrate the sickening length that some people will go to animate the most extreme and dangerous elements of their base regardless of the consequences,” Unga told NBC News. “And we have seen what these consequences are.”

https://iframe.nbcnews.com/ak3KjKw?_showcaption=true&app=1

The ad blitz in the last leg of the 2022 election cycle comes as transgender issues — and to an extent LGBTQ issues more broadly — have increasingly become a wedge issue in the nation’s culture wars.

A record 346 anti-LGBTQ bills have been filed in state legislatures around the country this year, including 145 that restrict transgender rights, according to the Human Rights Campaign. Many of the bills aim to restrict gender-affirming care for trans minors; prohibit trans girls and women from competing on girls’ sports teams in school; and bar the instruction of topics relating to sexual orientation or gender identity at school. This year alone, at least 12 bills restricting transgender rights have been signed into law, according to the American Civil Liberties Union. And on Friday, two Florida medical boards effectively banned gender-affirming care for trans minors who are not already undergoing treatment.

Homophobic and transphobic slurs and rhetoric have also had a resurgence within the nation’s political discourse this year. Conservative lawmakers and pundits have repeatedly accused supporters of LGBTQ rights, critics of legislation like Florida’s Parental Rights in Education law (dubbed the “Don’t Say Gay” law) and drag performers of trying to “groom” or “indoctrinate” children.

The word “grooming” — which has appeared in several of the recent election ads — has long been associated with mischaracterizing LGBTQ people, particularly gay men and transgender women, as child sex abusers. On March 29, the day after Florida’s pejoratively dubbed Don’t Say Gay bill was signed into law, the word “grooming” was mentioned on Twitter 7,959 times, compared with 40 times on the first day of this year, according to data pulled from Twitter by Alejandra Caraballo, a clinical instructor at Harvard Law School’s Cyberlaw Clinic.

The record-number of bills and surge of charged rhetoric has also coincided with a wave of acts and threats of violence against the LGBTQ community across the country. More than 1,300 hate-based incidents against Americans were motivated by their sexual orientation or gender identity in 2020, accounting for 16% of all biased-fueled encounters that year, according to the FBI’s most recent hate crime data.

“These targeted ads are taking place in swing states. Even convincing a relatively small number of voters to show up could be enough for some elections to change the results.”

GABRIELE MAGNI , LOYOLA MARYMOUNT UNIVERSITY

Perhaps most notably so far this year, police arrested 31 people at an annual LGBTQ Pride event in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, in June on charges of suspicion of conspiracy to riot. Those who were arrested went to the event with gas masks and shields. And just last month, a man lit and threw a molotov cocktail inside a doughnut shop in Tulsa, Oklahoma, after the shop hosted a drag event.

Gillian Branstetter, a communications strategist at the American Civil Liberties Union, said the ads are meant to boost turnout of conservative voters, particularly in battleground states.

“Broadly speaking, rhetoric and messaging against transgender rights are aimed at people who are already convinced that transgender people are a great evil to society,” she said. “All these ads are meant to do is to activate them and remind them to go vote on Tuesday.”

Gabriele Magni, an assistant professor of political science at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles and director of the school’s LGBTQ Politics Research Initiative, said that although the ads are polarizing for most voters, they could be quite effective.

“These targeted ads are taking place in swing states,” Magni said. “Even convincing a relatively small number of voters to show up could be enough for some elections to change the results.”

A poll released by the Pew Research Center in June found that a rising share of Americans say a person’s gender is determined by their sex assigned at birth. The survey of more than 10,000 adults, which was conducted from May 16 to 22, found that 60% of respondents said a person’s gender is determined at birth, up from 56% in 2021 and 54% in 2017.

The same poll also highlighted the country’s partisan divide over gender-affirming care, specifically, 72% of Republicans surveyed said it should be illegal for medical providers to provide this type of treatment to minors, compared with 26% of Democrats.

Many of the recent campaign ads targeting transgender rights were directed at Black and Latino voters, according to the Human Rights Campaign. Unga said this was a tactic to divide groups of voters who traditionally share common goals of achieving equality.

“This practice of ‘othering,’ of weaponizing marginalized people, feels all too familiar in these political spaces,” he said. “My warning for anyone who tries it is that you’re playing with fire.”

“Successful political movements,” he said, “are about addition, not division.”

Branstetter said the ads underscore the importance of turning out voters who are in favor of transgender rights.

“If trans people are going to be a priority for our enemies, we absolutely have to be a priority for our friends,” she said.