Young woman ‘with so much life ahead of her’ shot dead. She’s the 50th trans person killed this year

Nikai David, a “sweet”, spirited Black trans woman, has been shot dead in the US. She was 33.

The model, described by those who knew her as a “happy, fun person”, was killed in the early hours of Saturday (4 December) in Oakland, a port town in California.

Local law enforcement responded to a report of shots fired at 4am on Castro Street, West Oakland. David was found suffering from a gunshot wound only to die at the scene, FOX KTVU2 reported.

The Oakland Police Department said that there is no evidence of a hate crime.

An aspiring social media influencer who hoped to one day open a clothing boutique with her best friend, David had only the week before turned 33.

Friends had hoped to celebrate her birthday with her soon – a celebration that will now never happen.

David was a “beloved community member”, the Oakland LGBTQ Community Center said in a Facebook tribute Saturday. The group said it planning to honour her life with a memorial.

‘Nikai David was a young person with so much life ahead of her’, says activist

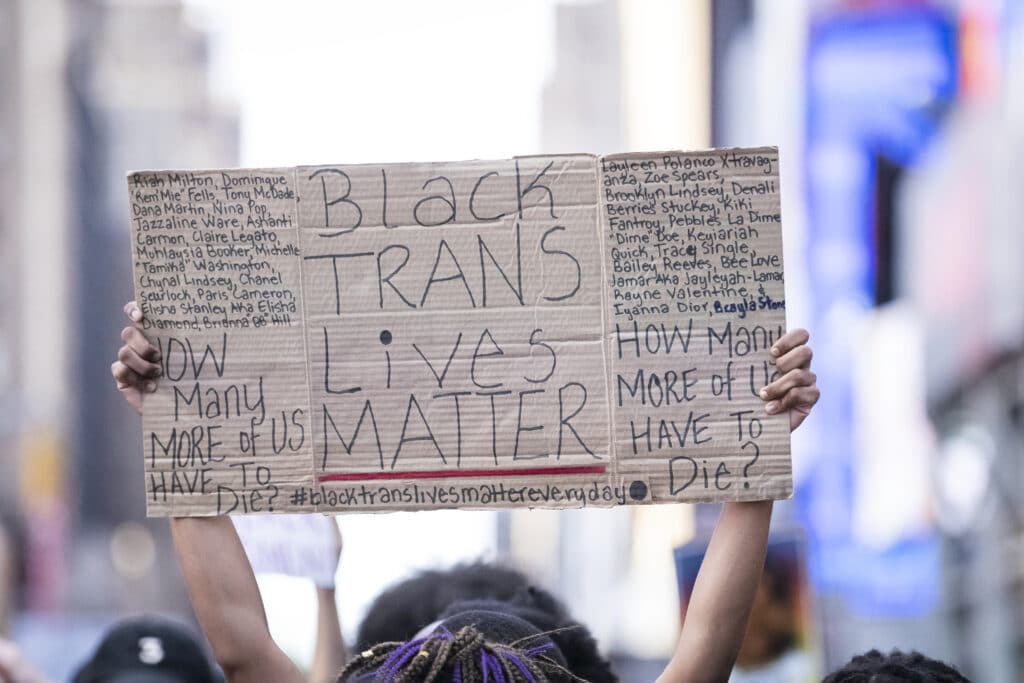

As a relentless “epidemic of violence” continues, 2021 has become the deadliest year on record for trans homicides in the US, according to monitoring groups.

David is at least the 50th trans, non-binary or gender non-conforming person violently killed in the US this year, according to the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), a queer rights group which has been documenting the slayings since 2013.

“Learning about Nikai David’s death is disheartening and alarming,” Tori Cooper, director of community engagement for HRC’s Transgender Justice Initiative, told PinkNews.

“In the year that we’ve marked as the deadliest year on record for our community, we continue to see a frightening rate of fatal violence against transgender and gender non-conforming people.

“We must all continue to demand that the violence cease.”

Cooper added: “Nikai David was a young person with so much life ahead of her.

“For her future to have been violently taken away from her serves as a reminder that we remain with so much work ahead of us to ensure a safe and loving world for all.”

The full death toll is likely to be far higher, the HRC has long warned. Almost three-quarters of trans homicide victims are misgendered and deadnamed by the police and local press, the group has found.

So far, the community has mourned across 2021: Tyianna Alexandra, Samuel Edmund Damián Valentín, Bianca Bankz, Dominique Jackson, Fifty Bandz, Alexus Braxton, Chyna Carrillo, Jeffrey ‘JJ’ Bright, Jasmine Cannady, Jenna Franks, Diamond ‘Kyree’ Sanders, Rayanna Pardo, Dominique Lucious, Jaida Peterson, Remy Fennell, Tiara Banks, Natalia Smüt, Iris Santos, Tiffany Thomas, Jahaira DeAlto Balenciaga, Keri Washington, Sophie Vásquez, Danny Henson, Whispering Bear Spirit, Serenity Hollis, Oliver ‘Ollie’ Taylor, Thomas Hardin, Poe Black, Novaa Watson, Aidelen Evans, Taya Ashton, Shai Vanderpump, Tierramarie Lewis, Miss CoCo, Pooh Johnson, Disaya Monaee, Brianna Hamilton, Kiér Laprí Kartier, Mel Groves, Royal Poetical Starz, Zoella Rose Martinez, Jo Acker, Jessi Hart, Rikkey Outommuro, Marquiisha Lawrence, Jenny De Leon, Angel Naira, Danyale Johnson, and Cris Blehar.