At San Quentin, LGBTQ Prisoners and Once-biased Inmates Try to Heal Together

Ten years ago, Rafeal “Nephew” Bankston landed in solitary confinement in San Quentin State Prison for refusing a gay cellmate.

“Where I grew up, we called it gay bashing,” he said. “We hated them, robbed them,” Bankston added matter-of-factly.

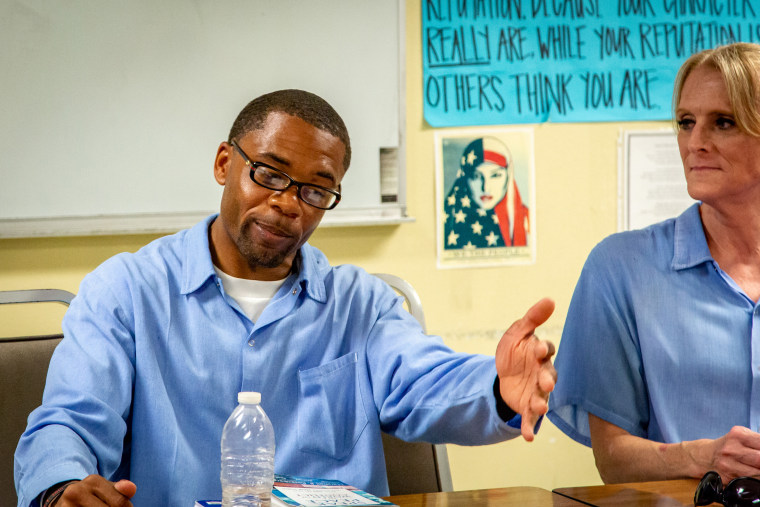

On a Wednesday afternoon in April, he told that story to a classroom of 15 other inmates. About half of them were LGBTQ. Photos of LGBTQ icons — Janet Mock, Ellen Degeneres, James Baldwin — smiled down from a whiteboard at the front of the room.

No one said a word. Lisa Strawn, 60, a transgender woman, was sitting next to Bankston and didn’t move.

Bankston, 37, was smaller than most of the others in the room. He wore plastic-frame glasses and a blue prison shirt that looked several sizes too big. Like many in the room, he has spent more than half of his life behind bars. He entered prison at 18 and said he learned at a young age to hate gay and trans people.

Half a life later, he wants to talk about Jussie Smollett. He wants to know how his LGBTQ peers feel about Smollett now that the TV star’s reported anti-gay hate crime has been refuted by Chicago Police.

Related

Georgia nonprofit is helping trans people adjust to life after prison

“When we walked out of here, here, everybody was pulling for him because it was wrong, how he got treated,” Bankston said. “Do you all still feel that way?”

He posed the question to members of Acting With Compassion & Truth, or ACT, a restorative justice group that meets weekly at San Quentin. Restorative justice is an alternative to punishment, one in which offenders and victims try to heal together.

‘I didn’t know where I fit in’

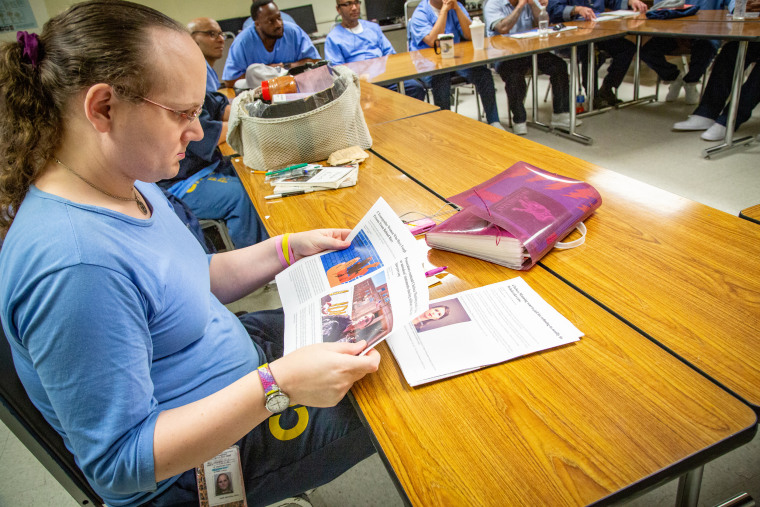

Each week for a year, LGBTQ and straight inmates meet for two hours in a small yellow classroom. They talk about everything from what it means that Janelle Monáe came out as pansexual to how to respect intersex people. Their goal is simple: heal together and work toward a better world for LGBTQ people.

Inmates Michael Adams and Juan Meza currently lead the group. The lessons have been designed by LGBTQ prisoners.

The group is as diverse as the world on the outside. Ages range from 25 years to late middle age, and races and ethnicities vary. Almost all of the attendees are what are referred to as “lifers,” those convicted of felonies so serious that their sentences range from many years to life in prison. These include murder and sex crimes.

Three of the group’s attendees are transgender women. Lisa Strawn is among them.

Strawn, who prefers no pronouns, entered prison 25 years ago on three-strikes burglary charges and has served much of that time at the California Medical Facility in Vacaville, another men’s prison. Strawn transitioned to female at age 18 but has always been housed with men.

That’s because in most prisons across the nation, transgender inmates are housed according to their birth sex, despite federal requirements in the Prison Rape Elimination Act that inmates be housed on a case-by-case basis.

Strawn has grown accustomed to navigating men’s prisons as a woman.

San Quentin is California’s oldest prison, built in 1851 by prisoners at the edge of the San Francisco Bay in Marin County. The views from the entrance are so heavenly it is often remarked that it’s astonishing the prison has not been flattened and divided up for real estate.

The 600-man cell block looms at six levels. There is no air-conditioning in the unit, and fans run in the background. Cells are just wide enough to stand in sideways. They house two people each and the sum of their possessions, crammed into cubbies above bunks. At one end of the cell block, men make calls from a line of pay phones. At the other end, they shower out in the open.

With a blond ponytail and carefully-applied eyeliner, Strawn decidedly stands out at San Quentin.

“Honestly, I’ve had problems, but then I guess myself personally, I think a lot of it is how you carry yourself,” Strawn said. “Every time I walk into a room I better own it.”

At Vacaville, Strawn helped establish an LGBTQ group. Leaving that a year ago to come to San Quentin was devastating.

“I hated this place when I got here,” Strawn said. “I didn’t know where I fit in, and I knew where I fit in there. But when I came here, I got into ACT.” Aside from the restorative justice group, Strawn also got into journalism by writing for the San Quentin news outlet, The Beat Within.

Transgender women like Strawn report exceedingly high rates of violence behind bars, according to data from the National Center for Transgender Equality. The 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey found that transgender people were nine times more likely than the general prison population to be sexually assaulted by other inmates.

It was due to that hostility that trans women approached the Insight Prison Project in 2015, where Billie Mizell was then serving as executive director. Inmates asked Mizell to support the formation of an LGBTQ education program at San Quentin. They didn’t want a support group.

“What I kept hearing from them was, ‘We live our lives here every day surrounded by thousands of people who have been for the last 20 or 30 years who haven’t had exposure to the evolution that we know is happening out there,’” Mizell explained, noting that the transgender inmates wanted to “bring that inside” the prison’s walls.

Working with several inmates, Mizell brought a yearlong curriculum to the prison. She has been leading the Acting With Compassion & Truth group as a volunteer at San Quentin ever since.

This year, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation allowed her to replicate the program on San Quentin’s death row, which remains intact despite California Gov. Gavin Newsom’s recent decision to halt executions. That group, comprised of five people, meets Tuesdays. It is not open to reporters.

ACT is entirely voluntary, although many admittedly come to the Wednesday class because it looks good for the parole board. Mizell, however, won’t let anyone in who is not genuinely committed to the lessons.

Still, the resulting class presents a strange juxtaposition. Prisoners, some convicted of extreme anti-LGBTQ hate crimes, spend a year in close proximity with the prison’s most vulnerable LGBTQ population.

‘I was so ashamed’

Among the group’s founding members is Phil Melendez, who faced 30 years to life in prison for two counts of second-degree murder, partially motivated by animus against a lesbian.

In 1997, Melendez’s father was stabbed while collecting a drug debt. Melendez justified avenging the assault because one of the assailants was a lesbian. On a phone call with NBC News, Melendez, who has since been released from prison, rattles off the slurs he used as he burst into a house and killed two people.

In prison, Melendez said he had a lot of time to think, not just about the crime he committed at 19, but about the homophobia behind it.

“I noticed that there was that element of LGBTQ bias in the slur that I used,” he said. “In that slur, I was actually dehumanizing a human being.”

Related

Trump administration rolls back Obama-era health care protections for transgender people

When the country debated marriage rights for LGBTQ people, he said found himself frustrated.

“I actually took offense at people who were against gay marriage,” he said.

So in 2015, when ACT started forming, Melendez took his own life experiences and used them to help design a curriculum for other straight peers in the class. Two years ago, Melendez was released. He is now a national advocate for restorative justice and LGBTQ rights.

Among those who benefit four years later from his work inside are attendees like Lee Xiong, who was struggling to face his younger brother who he suspected was gay. Trying to grapple with that, Xiong found ACT last year.

“I always thought that transgender or gay were nothing,” he says. “I thought it was a choice.”

Xiong has spent more than a year unpacking those feelings. When his brother came to visit him at San Quentin, Xiong asked his brother to come out to him. It took him five minutes to even reach the question.

“I was so ashamed,” he tells the group. “I asked him that question. Is he going to get hurt? Or is he in fear to tell me? But he just came out and said, ‘Yes man, I know what you’re going to ask me.’”

His brother told him that when he came out to their parents, they told him to “get the f–k out” and disowned him.

“I told him that, “You know what, don’t worry man, when I get out, we’ll talk to my mom,’” Xiong said.

This story, of straight prisoners connecting with LGBTQ family because of their time in ACT, is highly common. Bankston’s sister came out to him as transgender.

“I cut off communication,” Bankston said. “I don’t want to talk to you more. I don’t know what to say to you. Nobody likes you.”

Related

New York Yankees announce LGBT scholarship recipients at historic Stonewall Inn

But Bankston recently picked up the phone and called his sister. He asked how she was.

“He, excuse me, she ran with the whole rest of the conversation,” Bankston said, correcting himself on his sister’s new pronoun.

“It’s going to take some time and to adjust to my sister’s new lifestyle,” he explained. “I got some struggles with that. I’m not perfect.”

In May, Bankston’s sister agreed to come visit him at San Quentin for the first time since he entered prison 17 years ago.

The planned visit was a moment for the group to reflect on how far Bankston had come, according to Mizell. When he entered ACT, he was looking for a “chrono,” or a positive write-up to help his parole case. “And now I am out here being an ally, raising awareness and answering questions,” he said.

‘I was able to be authentically me’

Straight prisoners aren’t untangling their homophobia and earning parole at the expense of LGBTQ inmates in the group. For those who are LGBTQ, the group can be deeply healing.

“There was a time I would be deathly afraid of someone like Nephew,” 52-year-old Adams, tears pushing at his eyes, said of Bankston.

“This group is the first time I was able to talk about my lived experiences, as related to being a member of the LGBTQ community,” Adams said. “It was the first time I was able to be authentically me and also feel safe. That’s a profound feeling of humanity.”

Related

‘I’m gay’: Mormon Republican lawmaker in Utah comes out

Adams, who has been incarcerated for 19 years, struggled for years before coming out as bisexual publicly on San Quentin’s podcast, Ear Hustle, last June.

He noted that not a single man in ACT identifies as gay. “In here, it’s life or death,” he said of coming out.

The group aims to ease some of those challenges by adding to the number of allies on the inside.

In order to build this empathy, Meza tries to draws parallels between straight inmates and their LGBTQ peers.

He shows the class “The Genderbread Person,” a visual tool for talking about gender identity that resembles a Gingerbread man. He draws kind of a stick figure on the whiteboard. The group labels the person by distinguishing where different LGBTQ identities live: Anatomy is on your body; gender and sexual orientation are in your heart and brain.

“My culture would say that I’m a ‘two spirit,’ because I have the spirit of the masculine and the feminine at the same time,” Meza explained. “So it just really has to do with how I express myself and how I know myself.”

The group is then asked to rattle off words used to hurt marginalized groups: racist terms, sexist words, anti-LGBTQ slurs and hurtful terms for the incarcerated. Adams and Meza drew lines between the groups of terms, noting that insults hurled against prisoners, like “punk,” are also used to hurt LGBTQ people.

“Intersectionality,” Nythell Collins, 43, pointed out.

Meza noted that using the wrong pronouns for a transgender person can be just as harmful as a slur.

“We’ve said it many times, when we can’t express ourselves for who we are … a lot of the community ends up killing themselves,” Meza warned.

Class in April goes well over the allotted two-hour time. Egypt Senoj Jones, 25, a transgender, sings a song she composed herself, called “I Know.” She stands in the center of the arranged tables, her arms outstretched, tilts her head up toward the low ceiling vents and closes her eyes.

“I know what I gotta do,” she sang. “Now that I know the truth, there is no excuse.”

She sang about growing up in foster care, transitioning to female, dropping out of college and popping pills. She is snapping her fingers. By the end, the whole group is singing the chorus with her. She finishes and they erupt into applause.

Outside in the yard, Strawn poses for the camera in the sinking sunlight. Strawn beams in a movie-like pose, sunglasses glinting against the glare.

“This is how we do it at San Quentin,” Strawn said playfully.