Sodomy laws that labeled gay people sex offenders challenged in court

Nearly 20 years after the Supreme Court struck down laws criminalizing consensual same-sex activity, the legacy of sodomy bans is still felt across the United States.

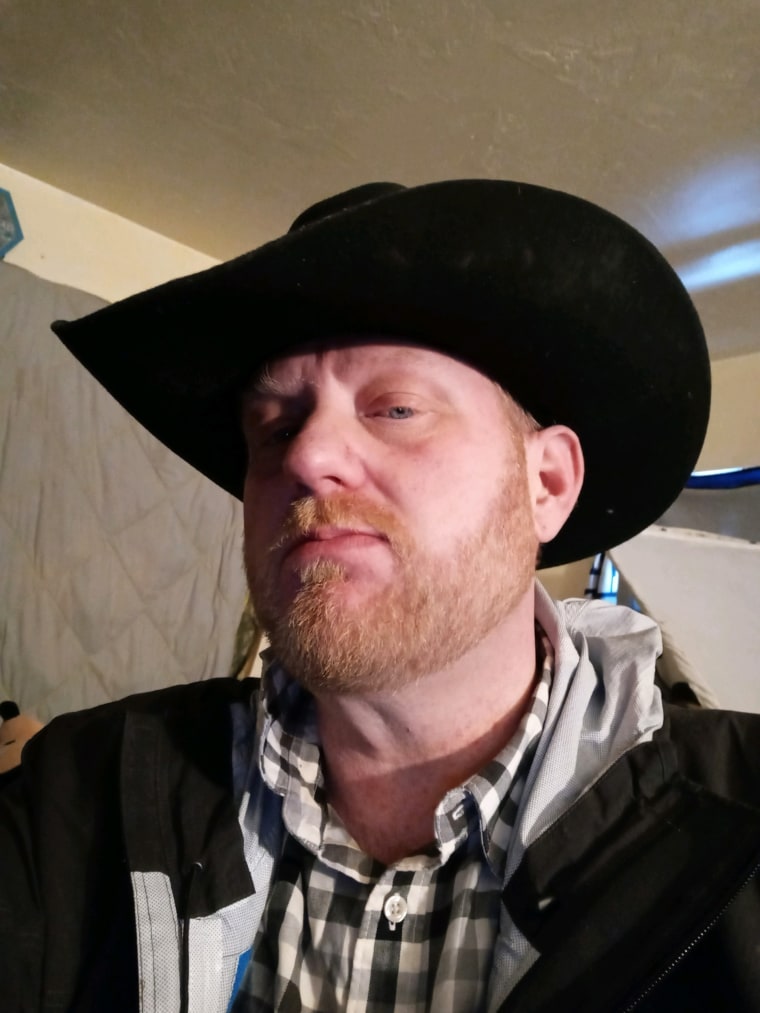

In 1993, then-18-year-old Randall Menges was charged under Idaho’s “crimes against nature” law for having sex with two 16-year-old males. All three worked and lived at Pratt Ranch, a cattle ranch in Gem County that doubled as a live-in foster program for troubled teenagers.

Menges was convicted despite police reports indicating the activity was consensual, and the age of consent in Idaho when a defendant is 18 is 16 years old. After serving seven years in prison, he was placed on probation and required to register as a sex offender.

Today, what Menges did wouldn’t be considered an arrestable offense. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2003 that laws criminalizing consensual sodomy or oral sex were unconstitutional. But Idaho still requires people convicted of sodomy or oral sex before the Lawrence v. Texas ruling to be on the state sex offender registry.

His attorney, Matt Strugar, has challenged a similar statue in Mississippi and is representing Menges and a John Doe in a suit against Idaho’s sodomy ban.

Idaho, South Carolina and Mississippi still require people who were convicted of consensual sodomy before the Supreme Court’s decision in Lawrence to register as sex offenders, Strugar said, even though the court said what they did wasn’t a crime. There are probably hundreds of people in Menges’ predicament, and forcing them to register as sex offenders is a violation of their right to due process and equal protection under the 14th Amendment, he added.

“I’m outraged that in 2021 that we have what is essentially a registry of gay sex,” Strugar said.

Hoping to start a new life, Menges moved to Montana in 2018.

“I love the mountains and taking care of horses,” he said. “And I thought the fewer people I had to deal with the better.”

Even before the Montana Legislature officially repealed the state’s ban on same-sex activity — which the Lawrence ruling declared unconstitutional — in 2013, people convicted under the statute weren’t required to register as sex offenders. But a law passed in 2005 mandates that individuals on a registry in another state must register as sex offenders if they move to Montana.

Menges filed suit in the U.S. District Court for the District of Montana in December, challenging the constitutionality of Montana’s policy. In filings shared with NBC News, he said being on the registry “has damaged dozens of employment opportunities and personal relationships.”

No one believes him about why he has to register as a sex offender, he told NBC News. “If they find out, I lose their friendship,” he said. “Even girlfriends, they don’t buy it.”

The same month he filed his suit, Menges said he was turned away from a homeless shelter in Boise, which he returned to temporarily in 2020.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Montana did not return a request for comment on the case. In opening arguments March 30, Montana Assistant Attorney General Hannah Tokerud argued Menges was trying to get a Montana court to weigh in on Idaho law.

According to the Missoulian, she said the case doesn’t hinge on the validity of that statute, but rather “it hinges on whether he is required to register in Idaho.”

“Montana requires Menges to register not because of his criminal offense,” the state wrote in a motion to dismiss in January, “but because Montana gives credit to other states’ determinations about convicted offenders who are required to register.”

“Idaho has determined that Menges must register, and thus, when Menges moved to Montana he was required to register,” the state wrote.

But Strugar said Montana is trying to “pass the buck” to another state while continuing to enforce what he calls an “unlawful” policy.

Menges isn’t seeking to overturn his conviction, he said — the statute of limitations passed a year after his conviction. He just wants to be free of the shadow that’s been cast over his life.

“If someone’s not a molester or a rapist, they shouldn’t be subjected to what I have,” Menges said. “If we can change the law, at least it’ll have been worth it.”

Ultimately he’d like to return to Montana, where the cost of living is lower and he can work with horses.

“I’ve had a passion for horses since I was 6. I’d like to get my equine veterinary nursing degree and take care of them, maybe for a rodeo or for private individuals,” he said. “I just want to go where I want and make the choices I want without this hanging over me.”