LGBQ people are six times more likely than the general public to be stopped by police.

Research has shown that lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer (LGBQ) youth and adults are disproportionately incarcerated. The root cause of LGBQ overrepresentation in the criminalization system is unclear, but scholars and advocates have pointed to police surveillance as one important factor.12 Reviews of LGBQ people’s experiences with police indicate a history of targeted surveillance—much of this documented in public spaces, like parks, and sex work domains.3 Here we present findings of a study of frequency and types of police interactions in a national probability sample of LGBQ people (Generations study). We compare these findings to results from the Police-Public Contact Survey (PPCS)—a survey of the U.S. general population conducted by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (see the Methods Note below for additional methodological details).

Results

Prevalence of contacts with the police

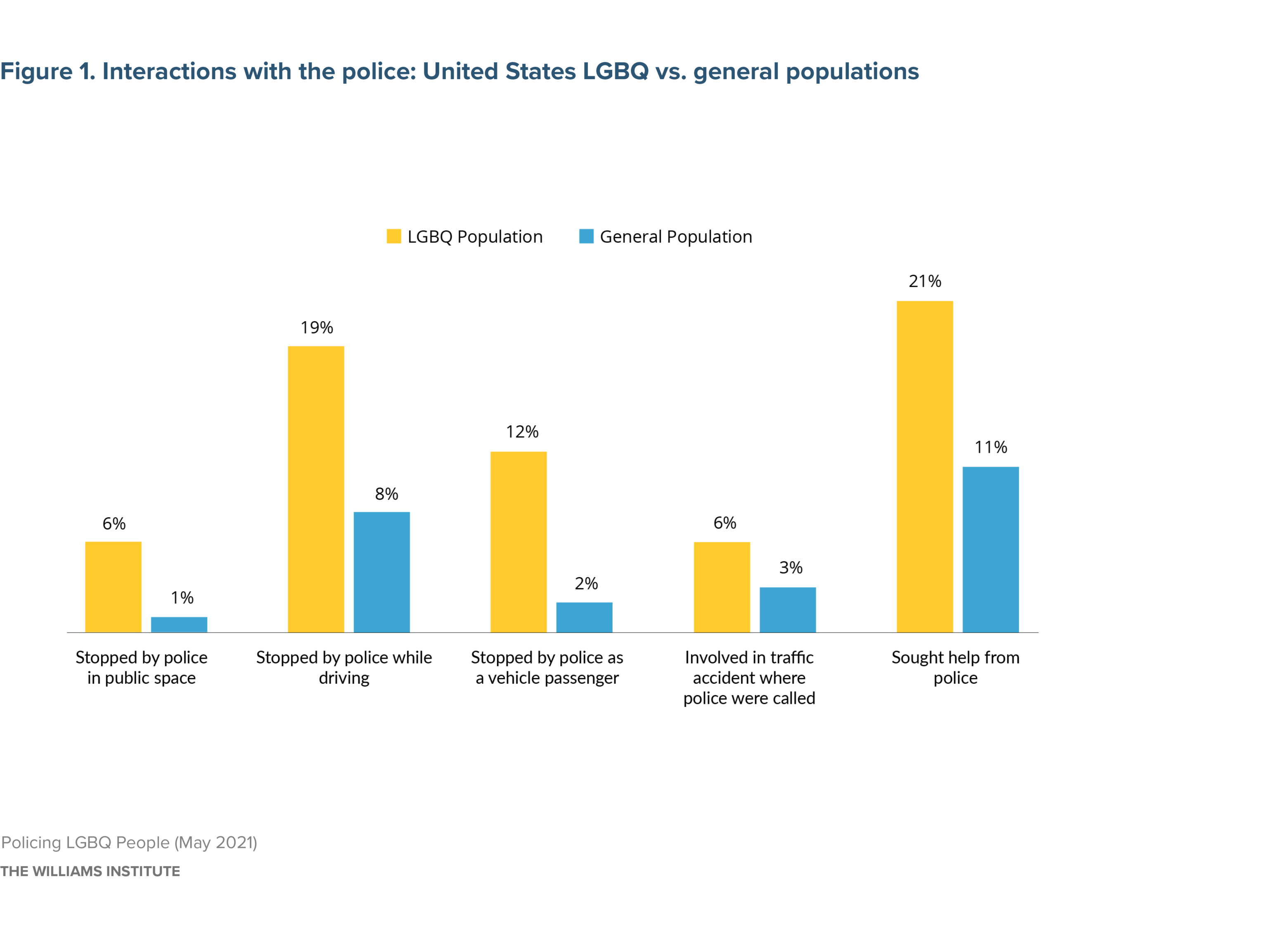

A larger proportion of LGBQ adults compared with the general population reported contacts with the police over a one-year period. This included being approached by the police, being involved in an incident that involved the police, and self-initiated contact with the police (Table 1). Compared with the general population, almost six times as many LGBQ people were stopped by the police in a public space (6% vs. 1%), and nearly seven times as many LGBQ people were stopped by the police for reasons other than involving a vehicle (driving or being a passenger). Additionally, twice as many LGBQ people approached or sought help from the police (22% vs. 11%) as compared to those in the general population.

Other findings include more common experiences of police stops while driving among LGBQ (19%) than non-LGBQ (8%) people, being a passenger (12% vs. 2%), or being involved in an accident to which the police were called (6% vs. 3%). The findings were similar across sex and race. In general, more LGBQ adults, both White and people of color, as well as female and male adults, reported contacts with the policy as compared with the general population. The groups did not differ in the average amount of contact with the police. Both adult LGBQ and people in the general population reported an average of 1.8 police contacts in one year, and this did not differ by sex and race. Among LGBQ people, 13% said they did not call the police even when they needed help (this was not measured in the general population so we cannot compare this figure). There were some statistically significant differences between Black and White respondents in the PPCS, but they are similar to the differences reported here for the general category of non-White. There were no statistically significant differences between Black and White respondents in the Generations sample (not shown).

Satisfaction with police interactions

The surveys then asked people to reflect on the most recent contact they have had with the police. Most people reported satisfaction with the police response in their most recent contact (Table 2). But compared with the general population, fewer LGBQ adults agreed that police behaved properly during their contact (81% vs. 91%). Additionally, more LGBQ people were unlikely to contact the police again (22%) as compared with the general population (6%). Fewer female LGBQ adults report satisfaction with the police (69%) compared to females in the general population (85%). Fewer female and White LGBQ people reported agreement that the police behaved properly (73% and 80%, respectively) compared to their peers in the general population (91% and 91%, respectively). Lastly, fewer female LBQ (33%), and both White and non-White LGBQ people (22% and 21%, respectively), reported that they were less likely to contact the police in the future compared to their general population peers (6%, 6%, and 7%, respectively).

*Bolded numbers indicate that the LGBQ group proportion is statistically significantly different than the general population proportion.

#The general population survey asks about participants’ “sex” with response options “male” and “female.” The data on LGBQ people come from the Generations study, which differentiated between assigned sex at birth and current gender identity. The LGBQ categories for female and male refer to sex assigned at birth. We use the term sex for consistency with the general population data. Transgender people were not surveyed in the Generations study and were not identifiable in the general population survey.

*Bolded numbers indicate that the LGBQ group proportion is statistically significantly different than the general population proportion.

#The general population survey asks about participants’ “sex” with response options “male” and “female.” The data on LGBQ people come from the Generations study, which differentiated between assigned sex at birth and current gender identity. The LGBQ categories for female and male refer to sex assigned at birth. We use the term sex for consistency with the general population data. Transgender people were not surveyed in the Generations study and were not identifiable in the general population survey.

Summary

More LGBQ adults than people in the general population have had interactions with the police, including when they were approached by the police and when they contacted the police. When we make these comparisons to the general population, we use this as a proxy for comparison to heterosexual cisgender adults, who make up 95.5% of the general population. The much higher rates of LGBQ adults reporting being approached by the police is consistent with the idea that LGBQ people are over-policed and raises the issue of bias-based profiling of LGBT communities in general.4 LGBQ adults are also less likely than people in the general population to report that the police “behaved properly” or that they would contact the police in the future. This may reflect the lower levels of trust the LGBTQ community has with the police, perhaps as a consequence of both over or under-policing, such as being stopped by the police for no cause, or when the police do not adequately respond to crimes against LGBT individuals. Notably, while LGBQ adults do not differ from the general population regarding satisfaction with the police, LGBQ women were less satisfied compared to women in the general population, which is perhaps a function of criminalization of non-heteronormativity of LGBQ women. Although data about transgender people were not available in the datasets analyzed for this brief, research indicates that transgender people, particularly women of color, are at heightened risk of negative police interactions, including harassment and assault.56 As police reform is being discussed nationally, it is important that reforms include attention to policing of LGBTQ populations across race and gender.

Methods Note

Dataset

To obtain comparisons between the general population and LGBQ adults in the United States, we utilized the Bureau of Justice Statistics Police-Public Contact Survey (PPCS) 20157 for the general adult population prevalence estimate and the Generations study,0 a national probability sample of LGBQ adults, for the LGBQ prevalence estimate. Weighted proportions and 95% confidence intervals were obtained using the recommended sampling weights. Analyses were performed using Stata 14. Statistically significant differences were determined by non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals (assuming an alpha of 0.05).