In 1947, Florida shut down a popular drag club. The state has resurrected that case to do it again.

In March of 1947, a Florida court ordered the Ha Ha Club — a nightclub famous for its “female impersonators,” as they were called at the time — to close after declaring it a public nuisance.

The order came just a month after Frank Tuppen, a juvenile probation officer with political ambitions, filed a complaint against the venue. He argued that the club’s performers were “sexual perverts” who had embedded “in the minds of the youngsters” who lived in the area “things immoral” and were “breaking down their character.”

The owner of the club, Charles “Babe” Baker, appealed to the Florida Supreme Court, but in October 1947, it affirmed the lower court’s decision that the club was a public nuisance. “Men impersonating women” in performances that are “nasty, suggestive and indecent” injure the “manners and morals of the people,” the court ruled.

Last month, nearly 75 later, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican who is widely thought to be eyeing a 2024 presidential run, cited the case that shut down Ha Ha Club in a complaint against Miami restaurant R House over its drag performances.

The 2022 complaint, filed by the Florida Department of Business and Professional Regulation, threatened to revoke R House’s liquor license, arguing that the establishment violated a state public nuisance law by becoming “manifestly injurious to the morals or manners of the people.”

Historians say the parallels between the R House and the Ha Ha Club complaints, and the fact that DeSantis’ administration cited a 75-year-old court decision, reveal how conservatives are resurfacing a decades-old moral panic about LGBTQ people to target queer spaces.

‘Seeding America with queer consciousness’

Baker first opened the Ha Ha Club in April 1933 in New York City’s Midtown Manhattan neighborhood, where it became “Broadway’s favorite hangout spot,” said Michail Takach, who researched the Ha Ha Club for a book he co-authored, “A History of Milwaukee Drag: Seven Generations of Glamour.”

Later that year, Baker traveled south and opened the club in Hallandale, Florida, about 13 miles north of R House, which is in Miami’s Wynwood neighborhood. He opened the club toward the end of the so-called Pansy Craze, which was a time period when drag surged in popularity, particularly in cities, Takach said.

Same-sex sexual relations were illegal at the time in most states, and cross-dressing was criminalized in many cities, though Miami never officially had an anti-cross-dressing law on the books. As a result, Takach said clubs like the Ha Ha Club catered primarily to seemingly straight, cisgender audiences, because drag drew attention and could be a liability to club owners.

However, Takach wrote in his book that female impersonator clubs offered gay and gender-nonconforming men that performed at these venues “a safe sanctuary where they could not only embrace their identities but make a name for themselves.”

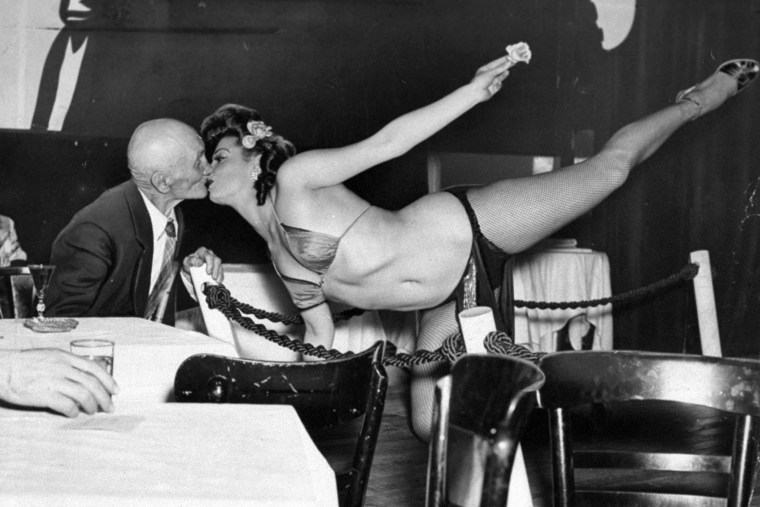

In Baker’s court testimony, he described how he stood at the club’s door every night and greeted all of the guests. The club held three shows from 9 p.m. to 4 a.m., with more than 40 performers who sang, danced and told jokes, according to court documents.

Baker featured some of the most famous female impersonators, including Jackie Maye, whose wardrobe was estimated at the time to have been worth $50,000, Takach said, which would be worth over $1 million in today’s dollars.

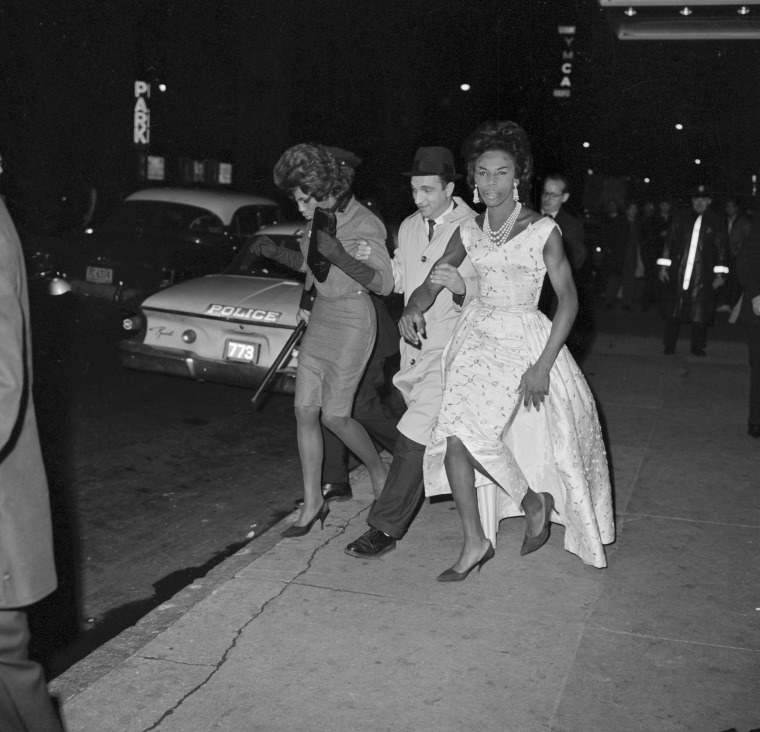

His production was also a traveling show, called the Ha Ha Revue, which was inspired by the Jewel Box Revue, a famous touring company of female impersonators — and the first racially integrated drag revue in the country — that operated from 1937 to about 1960, according to Takach’s drag history book.

The traveling version of the Ha Ha Club’s show and the Jewel Box Revue “really did a solid job of seeding America with queer consciousness,” Takach said. “And you have to wonder how much of that played into the gay liberation era — how many children that went to these shows, how many adults that watched these shows, were later part of the gay liberation scene.”

The shows brought queer representation to many cities across the U.S. at a time when gay people were being criminalized and also at a time when drag had fallen “violently out of favor,” Takach said.

“They brought it back in a big way and created a mid-century drag craze in the 1950s that, in some ways, is a parallel and a rival to the RuPaul drag craze of this decade,” he said.

‘A home of perverts, queers, phonies’

On Feb. 2, 1947, after operating his club in Hallandale for 14 years, Baker tried to stop a fight between two customers at the club and called the police. Both he and a customer were arrested for assault and battery, though Baker was never charged, according to court documents.

Just three days later, on Feb. 5, Tuppen — who was running for sheriff of Broward County in an upcoming election — filed his complaint against the club. He claimed multiple men he had arrested for having same-sex sexual relations said they frequented the Ha Ha Club.

James Lathero, the lawyer for the state, asked Tuppen what the general reputation of the Ha Ha Club is, and Tuppen said, “General knowledge, it is nothing but a home of perverts, queers, phonies.” Tuppen’s complaint also alleged that the venue had contributed to “juvenile delinquency” in the county that was “injurious to the manners and morals of the people” residing there.

Baker’s lawyers called more than half a dozen locals who testified that they enjoyed the club’s shows. Baker also testified that his cast had performed for a church and the Kiwanis Club and that it had raised money for the March of Dimes, a nonprofit organization that supports mothers and babies. He also denied that his club was associated with homosexuals and said there was no evidence of “crimes of perversion” at the club.

But the Broward County Circuit Court ultimately declared the Ha Ha Club a public nuisance and ordered it to close in the spring of 1947.

Baker appealed to the Florida Supreme Court, and one of his lawyer’s, Robert Lane, wrote in the appeal that there were no complaints against Baker’s club during its 14 years in business “until an aspirant for a political office decided to complain,” referring to Tuppen and his run for sheriff.

Lane also argued that “there are different views as to what may injure the manners and morals of the public.”

Get the Morning Rundown

Get a head start on the morning’s top stories.SIGN UPTHIS SITE IS PROTECTED BY RECAPTCHA PRIVACY POLICY | TERMS OF SERVICE

Despite Baker’s efforts, the Florida Supreme Court affirmed the lower court’s decision in October 1947.

“The lawful evidence presents a dirty picture; the Ha Ha Club looks as if it were a cross between a ‘honky tonk’ and a ‘speak easy,’” wrote Justice William Terrell, who later went on to defend segregation after the Supreme Court struck it down in Brown v. Board of Education. He added that the lower court determined that the Ha Ha Club’s “major connotations were evil, that it was exerting a corrupting influence and that the time had arrived to abate it.”

Recommended

OUT NEWSTransgender Harvard student dies in police custody while on honeymoon in Indonesia

OUT NEWSOne of the most powerful men in New York’s gay nightlife scene is accused of preying on young men for years

The case against the Ha Ha Club happened at a time when public support for drag had waned, because law enforcement and media nationwide claimed that gay people were a danger to women and children, Takach said.

“There was a very strong reaction to the liberation that people had felt, and the visibility that gay and lesbian people and gender-nonconforming people had earned during the Pansy Craze,” he said. “It led to many cities creating drag bans, shutting down drag clubs, banning female impersonation completely — silencing the queer nightlife and the queer representation that had really flourished during the Pansy Craze in the early parts of the 1930s.”

‘A cultural panic moment’

Last month, the Florida Department of Business and Professional Regulation alleged in its complaint against R House that a “nearly nude dancer was filmed parading a young girl through the audience” on or about July 3 and that the video ignited public outrage.

Inquired about it during a news conference, DeSantis said the video prompted the department to investigate further, “and what they found was not only were there minors there — and these are sexually explicit drag shows — the bar had a children’s menu. And you think to yourself: ‘Give me a break, what’s going on?’”

The complaint threatened to revoke R House’s liquor license and cited the Ha Ha Club case, noting that the Florida Supreme Court recognized that “men impersonating women” in the context of “suggestive and indecent” performances can constitute a public nuisance.

R House’s ownership said in an emailed statement last month that it is aware of the complaint and that it is working with the department through its attorney to “rectify the situation.”

“We are an inclusive establishment and welcome all people to visit our restaurant,” the email said. “We are hopeful that Governor DeSantis, a vociferous supporter and champion of Florida’s hospitality industry and small businesses, will see this as what it is, a misunderstanding, and that the matter will be resolved positively and promptly.” Ownership has not returned an additional request for comment.

There are multiple parallels between the Ha Ha Club case and DeSantis’ complaint against R House, historians said, revealing a cultural cycle.

Just as there was a public backlash to increasing queer visibility after the Pansy Craze, historians said conservatives are now pushing back against LGBTQ people winning major rights such as same-sex marriage.

But unlike in decades past, those who oppose LGBTQ equality cannot “attack gay people per se, so the people they attack are actually trans people or trans youth or drag queens, and then only in connection with children,” said Michael Bronski, a professor of women and gender studies at Harvard University and author of “A Queer History of the United States for Young People.”

Conservatives have increasingly criticized drag brunch performances, like those at R House, and Drag Queen Story Hour events as threatening to children. Some have even gone so far as to call them “grooming” and to call drag performers and other LGBTQ people and their allies “perverts” and “pedophiles,” resurfacing decades-old tropes and language that Tuppen used against the Ha Ha Club in 1947.

Bronski called the backlash against drag today part of a “cultural panic moment,” and Takach said it’s happened throughout history in the U.S.

“People get drawn in by the glamor, and it’s a novelty,” he said of drag, “and then something happens, and the entire community turns on it.”

Maxx Fenning, the president and founder of Prism, a nonprofit that works to expand access to LGBTQ-inclusive education in South Florida, said the complaint against R House, like the one filed against the Ha Ha Club 75 years ago, shows how laws related to “public morals” can be used to disproportionately censor LGBTQ people and topics.

“This Florida Supreme Court case noted that men impersonating women is not in and of itself a verifiable offense, but it’s doing it in an indecent fashion,” he said. “You see very often this use of vague and subjective language to be able to create laws and rulings that seem common sense, but have just enough vagueness to be applied in ways that unnecessarily silence the queer community.”

As for the Ha Ha Club, Babe Baker didn’t shut down his performance after the club was forced to close. In fact, he moved it to about a mile away, to a club called Leon & Eddie’s, a nightclub first opened in New York City by Leon Enker and Eddie Davis and later moved to Miami.

He also started advertising in a “curious” fashion, Takach said. He placed ads in the Miami Herald that prominently featured the word “gay” in phrases like “gay laughs,” “gay surprises,” “gay faces,” “gay music” and “gay dancing.” Even though gay wasn’t widely used at the time to refer to queer people, Takach said Baker chose the word intentionally.

Prior to opening the Ha Ha Club in New York, Baker worked at the Howdy Club, which Takach described as “an unapologetic lesbian bar” and one of the first places in Manhattan to hire lesbians as entertainers and allow women to gather and drink without male company. Takach said it was raided by police regularly, and that the word “howdy” became synonymous code for queer.

The word “gay” similarly became a code in Baker’s newspaper ads, and the Miami Daily News caught on in 1952, Takach said. The paper criticized the Miami Herald, its competitor, for running ads for clubs like Baker’s on one page and then condemning the clubs in the Herald’s editorials. “The words ‘gay,’ ‘ha ha’ and ‘howdy’ have become beacons pointing to the hands of the perverts,” the Miami Daily News wrote, according to Takach.

Baker’s cast performed four times a night at Leon & Eddie’s, and they also went on tour across the country, selling out weeks of shows in cities including Milwaukee; Detroit; Dayton, Ohio; Minneapolis; and Spokane, Washington, Takach said.

“You could say that Broward County won the battle, but Babe Baker won the war.”