Archive activists are on a global rescue mission to save LGBTQ+ history

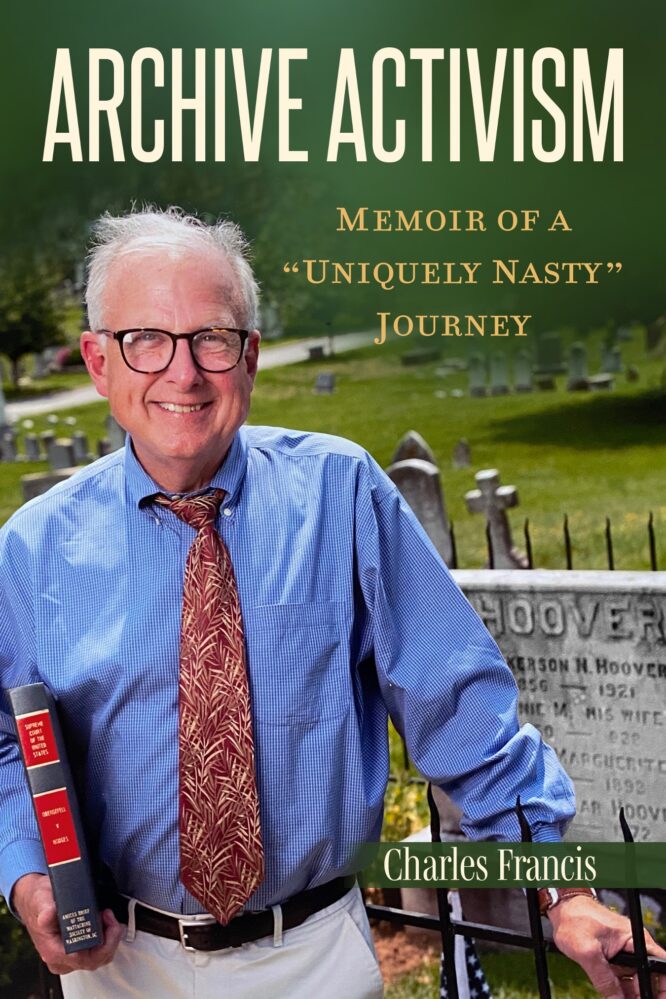

That’s me grinning at FBI director J. Edgar Hoover’s grave on the cover photo. I am relishing this moment. Like the millions of tourists who annually visit Washington for selfies and pics in front of their favorite attractions, I chose a grave for a feel-good image of my own. I, a citizen “sex deviate”—the pejorative and crime invented by Director Hoover decades ago—returned for a reckoning of my own. It took a lifetime for me to be able to stand here with a smile, no trace of anger, on my face.

I could have chosen other places and moments to tell my story—from White House ceremonies and holiday parties to Supreme Court hearings and events at the Library of Congress and the Smithsonian Institution exhibiting our work. Or maybe standing before a bower of plastic flowers with my husband at our marriage at the DC Superior Court. But this place is it—J. Edgar’s neatly fenced grave, a packaged plot for the tourists and dog walkers at Congressional Cemetery in Washington, DC. Here I can mark the distance LGBTQ Americans have traveled since his creation of the FBI Sex Deviates program in 1951, the year of my birth in Dallas.

I hold my bound copy of the Mattachine Society of Washington, DC’s amicus brief submitted to the Supreme Court in the case of Obergefell v. Hodges, the same-sex marriage victory that opened the door for a million LGBTQ Americans to marry those whom they love. That victory is now protected by federal law. This “friend of the court” brief presents our case for same-sex marriage.

Dubbed the “animus amicus” by the Washington Post, it steadies and delights me because it tells stories of endurance and courage we uncovered because they were erased or forgotten. “Animus, therefore, was a culture,” our brief declares. “And with that culture came a language. For decades, government officials referred to homosexuality in official, often highly confidential or privileged communications, as ‘unnatural,’ ‘abnormal,’ ‘immoral,’ ‘deviant,’ ‘pervert(ed).’ An ‘abomination.’ ‘Uniquely nasty.’”

From where I stand, going back in time to J. Edgar’s Sex Deviates program, one can measure the distance between our era and his. I was once so enmeshed and implicated in the long history of hiding that the liberation side of life’s equation would only come decades later, like a late blooming. For me it started atop a rickety pull-down ladder into a dusty attic—and with a new way to converse with history we call Archive Activism.

We all know the well-worn observation “Those who cannot remember the past are doomed to repeat it.” But what if you cannot find the past? What happens when all evidence, every shred, has been erased, deleted, sealed, or purposefully forgotten? What if the past is torched or stuffed into garbage bags and dumpsters? For LGBTQ Americans this has been the way of our world. “This Didn’t Happen” is the sign over the iron gate. Homosexual is an adjective, not a noun. You don’t exist. You are a behavior. Your uncle’s old love letters embarrass the family. No politics for you. History is for a people, not for queers.

Breaking through this was the challenge of the first generation of pioneering LGBTQ community historians and activists who succeeded beautifully at confronting the invisibility and the lies. But it is never over. The historic animus has seeped down into the dark and violent corners of American life. Today, a This Didn’t Happen movement called Don’t Say Gay flourishes.

Archive Activism is a rescue mission for primary archival materials located in archives and libraries, large and small, worldwide. It is preservation-minded movement to recover and protect historical queer memory. Archive Activism is a populist mission to recover the erased past and to document the government animus that continues to course through LGBTQ political and policy history. It is a popular brand of citizen archivery representing those living or passed who were wrongly investigated or silenced, their lives and careers thwarted or destroyed.

Internationally, Archive Activists uncover the names of those killed or “disappeared.” This is not an approach for scholars or professional historians. It is freeing not to hoard research or wait for book deals or seek tenure. Rather, Archive Activists use their discoveries and the power of history to fight for social justice, equality, and even our own safety. We believe it is possible to be armed with library cards. Archive Activists wield documents and let them speak for themselves. The Latin phrase “vox populi,” the voice of the people or public opinion, may be less important than the power of the documentary evidence itself, the “vox docs.”

***

“What it boils down to is that most men look upon homosexuality as something ‘uniquely nasty,’ not just a form of immorality,” wrote US Civil Service Commission lawyer John Steele in his influential 1964 policy memorandum addressing gay and lesbian “suitability” for federal employment. His rationale banned us from earning a living—and a life. From postal clerks and air traffic controllers to postal clerks and soldiers, we were done; “once a homo, always a homo,” he wrote.

Uniquely nasty.

Worse than plain nasty. Really?

How did that happen?

In my youth I did some mean things and had some “nasty” thoughts, but uniquely so?

In Dallas in 1964, I am working on my Eagle Scout, preparing to run for student council president, and starting to crush on a guy in my class. My seventh-grade friends and I are all into British director Richard Lester’s black-and-white film A Hard Day’s Night, especially the Beatlemania shot of the band sprinting through a London tube station. I imagine myself running with them, definitely not on the Elvis side of the continental divide. The Beatles, sucking up to Texas, wore cowboy hats when they arrived at Dallas Love Field. This was probably their gay manager Brian Epstein’s idea. He loved to dress them up. This set my adolescent energy in motion. I join an all-night line with a bedroll at the Preston State Bank in University Park to buy my Beatles tickets. The kid next to me is wearing his Beatles wig, and I like that better than the cowboy hats.

We are in a new world, teen sixties Dallas. Running fast in a mania of our own, past questions without answers, it has been one year since Dallas’s darkest day, the day on which John F. Kennedy was assassinated. Are we truly a City of Hate? Confronted by historic hatreds, it is our teenage time of innocence lost. Taking a lot of our cues and all of our soul off Dallas white radio (white radio? Even radio is segregated) from breakthrough Black DJ Cuzzin’ Linnie, we keep running. Cuzzin’ Linnie is not about Liverpool; he’s playing Memphis. We know it is time, our time for change. Still, so many are dead set against LBJ and his “communist” ideas like civil rights. Our congressman Bruce Alger voted against the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960—and he will do so again.

How could we know in such a time that an epithet like “uniquely nasty” struck at one’s core, deeper than just “immorality”? Immorality we could do something about. We realized that, according to the papers we unsealed and the boxes we discovered many decades later in people’s attics, the National Archives, and elsewhere, this insult was an organized, bipartisan federal assault. I and millions more like me, spanning generations, Black and white, invisible and unknown to one another, were assigned to this subaltern place before we even knew the words used to denigrate us.

In the years to come, we would uncover those words to examine them not as lies, but as living things. Still used to shock and stun, a lot of them are rattlesnake ugly, discovered under flipped rocks. We find them inside classified, sealed, hidden files that are part of the vast American archive. We breathe deeply the dust and blood rising off the old carbons with traces of that mimeograph smell that make you dizzy. Words like deviate, pervert, revulsion, suitability, insanity, disordered, dishonorable, disloyal, and groomer anger us—and then inspire our work to ensure none of this is erased or can ever happen again.

Our activism was born in these forgotten papers—and lies—generated decades ago, retooled and weaponized for our time. Whether slimed as perverts in the fifties, compared to “man on dog” years later in Texas, or defiled as pedos and groomers today, it is the same personal and political calumny.

Running still, I hit the intersection of history and memory. It was in Dallas where I first engaged with the idea of history itself.

*For more information on Archive Activism or to purchase the book, visit the UNT Press website.