New exhibit highlights LGBTQ legacy of Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was one of the most important artistic and cultural milestones in modern history, and a sweeping new exhibit at The New York Historical highlights how this era was — as Henry Louis Gates Jr. once put it — “surely as gay as it was Black.”

This perspective rings true for Allison Robinson, the lead curator of “The Gay Harlem Renaissance.”

“In school, we tend to learn that the Harlem Renaissance was focused on race and class, and the things that they’re producing, but in fact, sexuality and gender are just as important,” Robinson told NBC News.

The Harlem Renaissance was marked by an explosion of Black creativity, identity and intellectual life centered in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood during the 1920s and early 1930s, though Robinson noted that historians debate exactly when it ended.

The era, Robinson said, gave Black artists “an opportunity to express themselves in ways that had not been done before,” adding that “Black queer creatives are really a driving force” during this period, even amid racism and homophobia.

“The Gay Harlem Renaissance” — which features more than 200 items including paintings, sculptures, photographs and books — opened Friday and will remain on view until March. George Chauncey, a professor of history at Columbia University and the author of the seminal LGBTQ history book “Gay New York, 1890-1940,” served as the show’s chief historian.

Exploring Harlem’s art

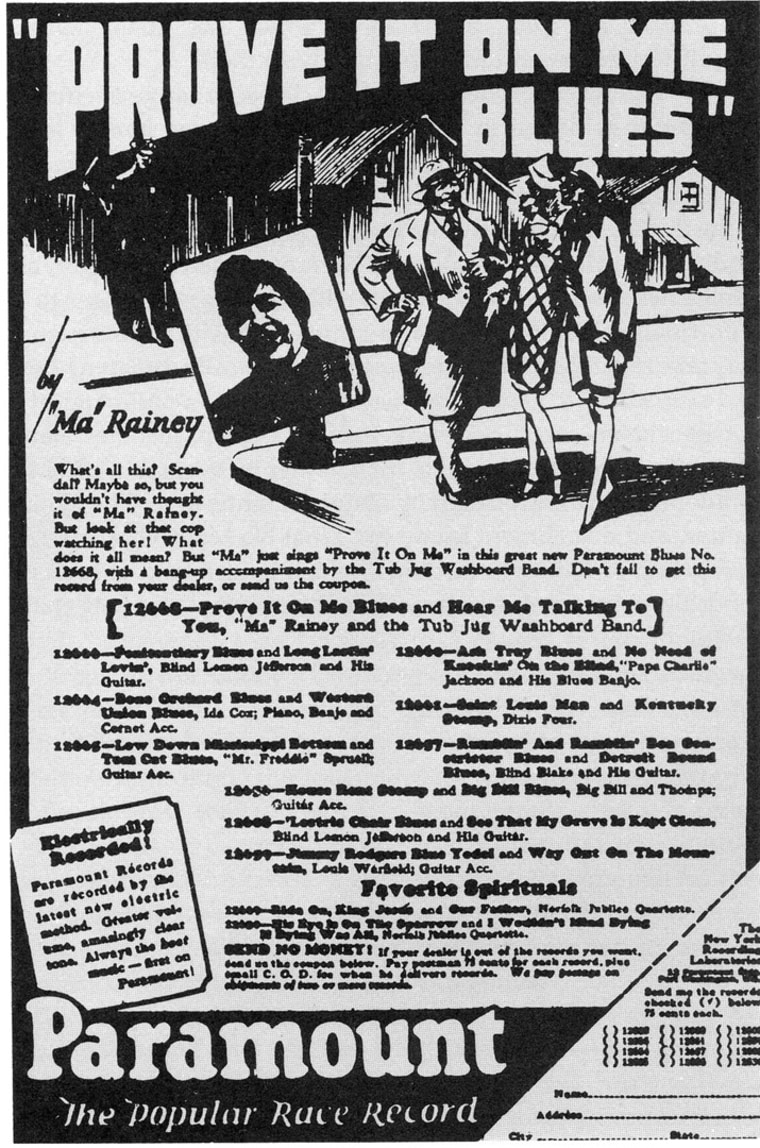

The multiroom exhibition takes visitors through the Great Migration of Black Southerners in the early 20th century; introduces them to the groundbreaking works of writers like Alain Locke, Langston Hughes and Bruce Nugent; leads them through the speakeasies, rent parties, drag balls and salons of the interwar years; explores the soulful blues music of entertainers like Ma Rainey, Ethel Waters and Bessie Smith; and examines the lasting legacy of the work produced during this rich cultural era.

Locke, considered the “dean” of the Harlem Renaissance, edited and published “The New Negro” in 1925, a seminal anthology for the movement. Locke, who was gay but not out, mentored many of the poets, novelists and artists who defined the era, such as Countee Cullen, Hughes and Nugent.

Robinson said Nugent stood out in Black art at the time for openly embracing and celebrating beauty — a theme captured in his 1926 stream-of-consciousness poem “Smoke, Lilies and Jade,” published in the short-lived magazine “Fire!!” The piece reflected his attraction to both men and women.

Though “Fire!!” only published one issue, it was one of several magazines featured in the exhibit that helped ideas about freedom, sexuality and identity reach beyond Harlem.

Drag, nightlife and defiance

Drag was a popular art form during the era, and Harlem’s annual Hamilton Lodge Ball was the largest and most famous drag ball on the East Coast.

“By the time you hit the 1920s and ’30s, attendees numbered in the thousands, and they’re coming from up and down the East Coast and as far as Europe to come see the participants perform,” Robinson said.

The event became so legendary, Robinson said, that it was covered in newspapers around the world and was even written about by Langston Hughes in his 1940 autobiography, “The Big Sea.”

Nightclubs and speakeasies were also central to Harlem’s social life. The exhibit pays homage to these venues with a large re-creation of a Harlem nightlife map, highlighting popular spots that catered to gay and straight patrons and drew crowds from across New York City.

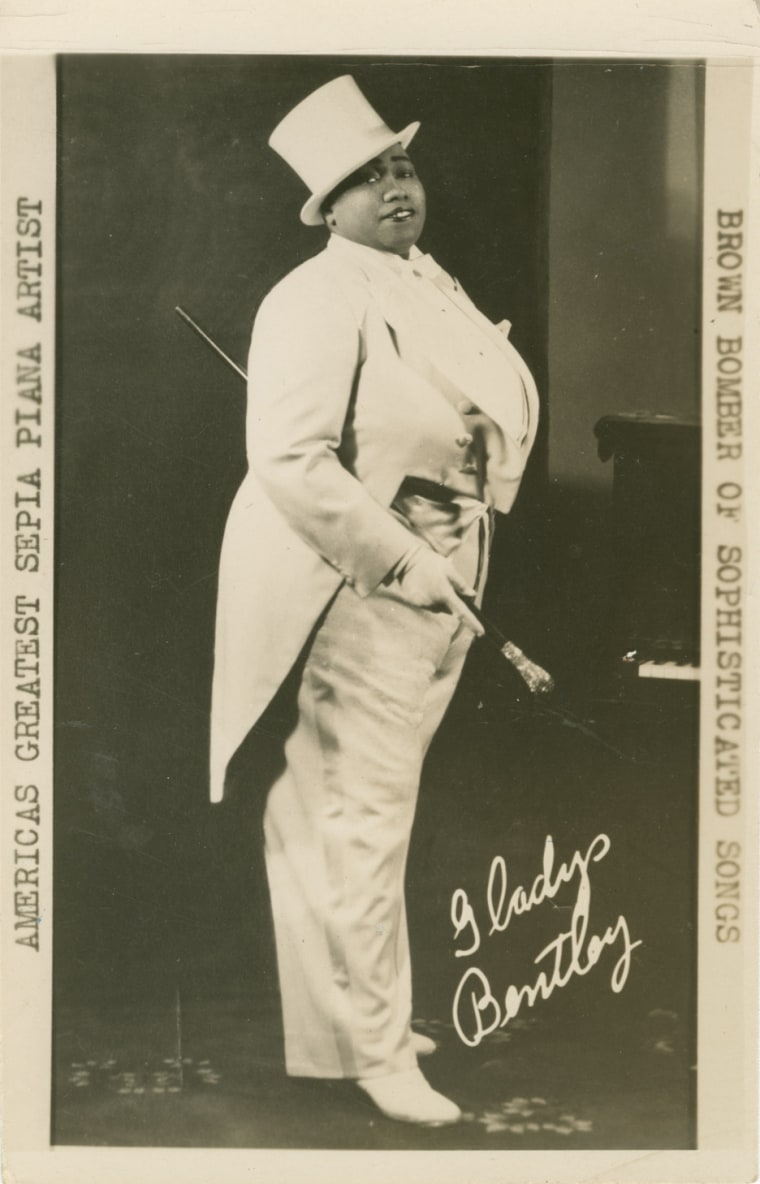

One such venue was Gladys’ Clam House, home of arguably the era’s most famous gender-bending performer: Gladys Bentley. The nightclub was initially named Harry Hansberry’s Clam House, but Robinson said the owner eventually renamed it for the tuxedo-clad performer because she’s “why people were going.”

Bentley got her start at rent parties in private homes before breaking into the Harlem nightclub scene when the Mad House was looking for a male performer. She offered to perform in a top hat and a tuxedo coat, a look that became “her signature for the rest of her career,” Robinson said.

But her masculine style wasn’t just for the stage.

“This is part of her life,” Robinson emphasized. “She’s walking up and down Seventh Avenue with a woman on her arm, dressed in a tuxedo and a top hat.”

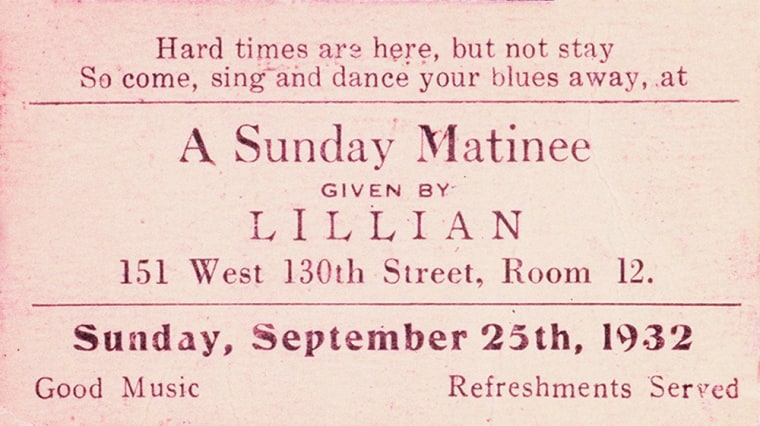

Rent parties, the type of events where Bentley got her start, were popular in Harlem at the time.

“Rent in Harlem was astronomical,” Robinson explained. “Landlords took advantage of the fact that there were limited places where Black people could live to charge them extremely high rent, but individuals threw parties to help cover the cost.”

For a small fee, guests at these Prohibition-era parties could enjoy illegal drinks as well as music and dancing, Robinson explained. It was a way for Harlem residents, gay and straight alike, to socialize and help cover the high cost of rent.

Thirteen rent party invitations are displayed, all but one coming from Langston Hughes. The other, for a “Sunday matinee,” came from Lillian Foster, who gave it to a dancer named Mabel Hampton after the two struck up a conversation at a bus stop. The women became romantic partners for more than four decades, and Hampton kept the invitation for the rest of her life.

The Harlem home of arts patron and LGBTQ ally A’Lelia Walker was not just a place for revelry but also for the convergence of ideas and collaborations.

The only child of entrepreneur Madam C.J. Walker, A’Lelia held salons and parties bringing hundreds of people together to her apartment and later a grand townhouse on 136th Street, known as the Dark Tower. Her parties became safe havens for Harlem’s queer community, with Hughes calling her the “joy goddess of Harlem’s 1920’s.” Correspondence and one of Walker’s stylish coats from her salon era are included in the exhibit.

The artifacts celebrating the Harlem Renaissance’s LGBTQ legacy tell a story that is still unfolding, Robinson said. “The end is not an end, but a display of what came after,” she said.

Robinson said she hopes visitors “appreciate what amazing creative energy is coming out of the Black LGBTQ community in the ’20s and ’30s”; that they understand that sexuality and gender are important “topics that are being investigated in the Harlem Renaissance”; and they “realize that even as the figures here were facing a lot of obstacles, they’re producing things that are beautiful and moving and important.”