Latino families with trans minors fear new laws limiting medical treatment: ‘It’s what’s kept my daughter alive’

As a 7-year-old, Adelyn Vigil believed death was the way to be able to live as a girl.

Adelyn’s nightly prayer to God was to become a bird to be able to fly, then die and then be made into a girl.

“I was crying and I told her: ‘Oh, but mom, it’s going to take a long time, because first I have to die as a boy and then as a bird and then be a girl,” Adelyn, 14, told Noticias Telemundo about the conversation with her mother years earlier.

“The only thing I could say without crying was: ‘You know you don’t have to die,’” the trans teen’s mother, Adamalis Vigil, said in an interview, recalling the conversation. “I said, ‘If that’s what’s going to make you happy, you can do that. You don’t have to die.’”

Adelyn usually speaks with a smile, except when she starts talking about what makes her afraid: The estrogen hormone treatment she started a year ago is running out and she was left without a doctor after Republican Texas Gov. Greg Abbott signed state Senate Bill14 at the beginning of June. The law bans medical professionals from prescribing drugs to block puberty, hormonal therapies and gender transition surgeries on minors under 18.

The law “is going to be the toughest battle we’re going to face,” Adelyn’s mother said. The advice of a team of specialists and specialized medical care “is what has kept my daughter alive,” she added.

Adelyn is one of nearly 30,000 people ages 13 to 17 who identify as transgender in Texas, according to data from the Williams Institute at the University of California, UCLA. It’s the largest young transgender population of the nearly 20 conservative states that have passed similar laws in recent months.

Adelyn, who wants to be an attorney like Elle Woods (Reese Witherspoon) in “Legally Blonde” when she grows up, wants to move to Washington, D.C., work in human rights and someday be a mom.

“It’s crazy what these legislators are trying to do, someone has to stop them,” Adelyn said about the state bill.

At least 64 bills against trans people have been introduced in Texas and four have passed, according to a count by Trans Legislation Tracker, an advocacy group that tracks these pieces of legislation around the country.

Those who promote and support laws banning gender-affirming care for minors, including puberty blockers and hormones, believe they are too young to make these kinds of decisions about their bodies and that the care is too experimental.

Gender-affirming care is supported by major medical organizations, such as the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Psychological Association.

‘I knew I was in the wrong body’

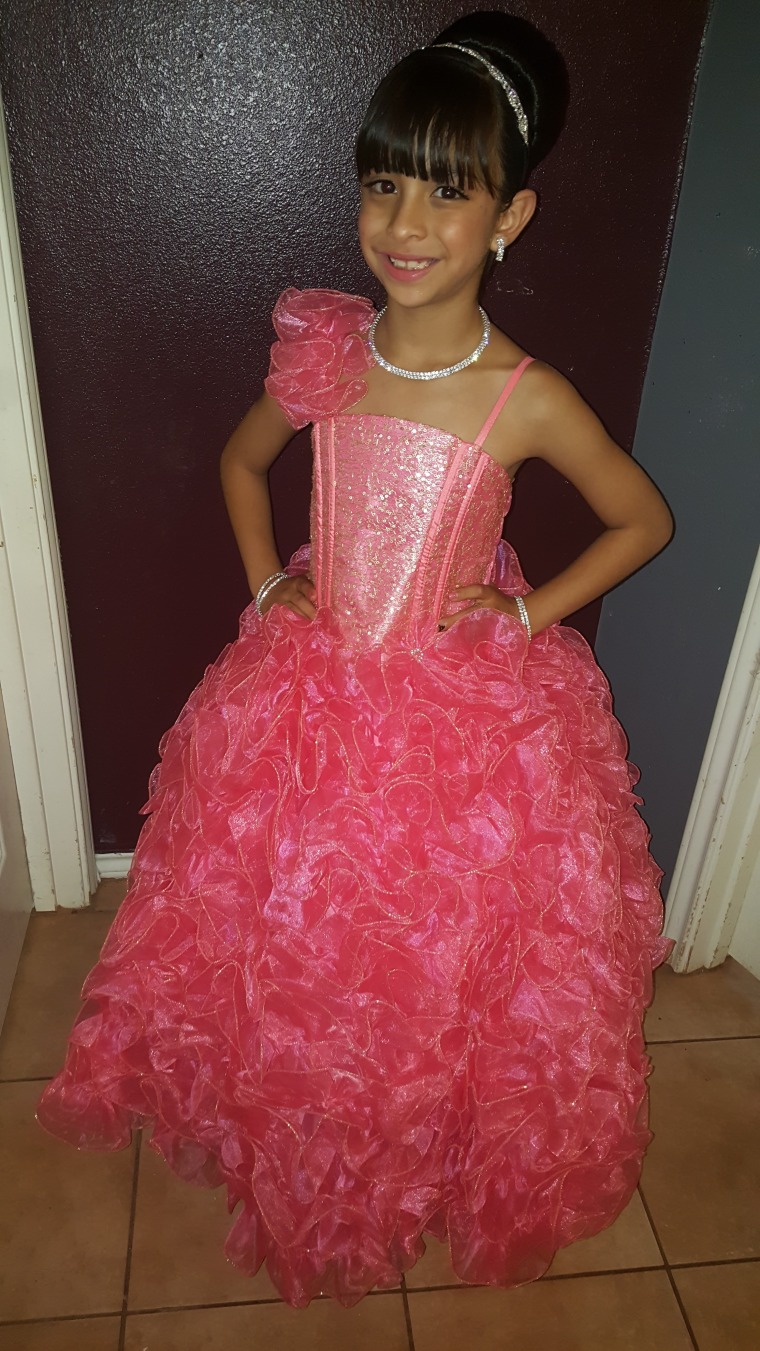

Adelyn spoke to Noticias Telemundo before her 15th birthday on July 24. She was emotional when talking about her quinceañera party — a tradition in Latino families when a young woman turns 15 — and she was excited about her dress, which had crystals, sequins, a bow and a layer of tulle. She bought it in Mexico, where her family is from.

According to Adamalis, the first signs regarding her child’s gender identity came early, when Adelyn was 3 years old. One day, Adamalis was sorting clothes in her closet and Adelyn saw a fuchsia party dress with crystals and asked her mom not to donate it. “When I grow up,” Adelyn told her mom, “I’m going to be a woman and I’m going to wear it.”

Adamalis told the child, “It doesn’t work like that, when you are born and you are a boy, you grow up and become a man,” she said. “And when you are born and you are a girl, you grow up and become a woman. It doesn’t work any other way.”

Adamalis said she tried to get information to understand what was happening and after much searching, she came across articles about trans people. “I had a word for what was happening to Adelyn,” she said.

“I knew I was in the wrong body,” Adelyn said. For Adelyn, there was first a social transition: buying girl’s clothes and shoes, growing her hair, changing her name and telling her family, friends and staff at her school who she was.

“My first instinct was to take her to the doctor,” her mother said. A pediatrician “examined her physically and he was the one who told me: ‘Your first step is going to be to take her to a counselor, a psychologist and talk to the school.’”

Transgender people like Adelyn often experience “a true disconnect between their birth-assigned sex and their inner sense of who they are,” according to the Human Rights Campaign. The anxiety caused by this disconnection has been referred to by doctors as gender dysphoria, since it can cause severe pain and anguish in the lives of trans people.

She was “very sad all the time and would come home and cry,” Adamalis said.

Medical treatments, then a law banning them

For Adelyn, puberty blockers weren’t an option until she was 13 years old; then, after intense and prolonged medical care and assessments, she started hormone therapy with estrogen for a year. The treatments allow her to maintain a finer voice and prevent her from developing masculine features such as a prominent Adam’s apple.

Adelyn said that Texas’ ban on this kind of treatment for minors is “as if the lawmakers are telling you: ‘No, you can’t be you anymore’; ‘wait, wait.’ But if I wait, I will see myself as a man — I don’t want that,” she said, adding that is one of her biggest fears.

Puberty blockers “temporarily stop this process of change and give the adolescent and their family members the opportunity to explore a little more what their options are in the future,” said Dr. Uri Belkind, associate medical director of Adolescent Medicine at the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center in New York.

There are a series of protocols and medical criteria that must be followed before prescribing hormones and they’re not recommended for children who have not yet started puberty, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Puberty blockers, according to the Mayo Clinic, “do not cause permanent physical changes” but may affect growth, bone density and fertility, “although it depends on when the medication is started.” That is why they recommend that each case be evaluated specifically and that patients have a specialized medical team.

“We have enough evidence to say very clearly that these drugs are medically necessary, that they produce benefits, that the benefits outweigh the risks, and that, in one way or another, they improve quality of life and even save lives,” Belkind said.

That’s why the bill worries Adamalis.

“Of all the battles, I think this is the worst, because this kind of help is what has kept my daughter alive,” Adamalis said about her daughter. “When I found her [medical] team, she was happy. Her anxiety went away, her panic attacks went away,” Adamalis said.

Laws like the one in Texas, said Belkind, prevent medical professionals like him from providing patients the care they need, and by not having access, “they see their body getting further and further and further away from the idea that they have of themselves.”

This is dangerous because it generates anxiety, depression and stress. “We know that suicide rates increase in patients who don’t have access to this type of medication,” Belkind said.

Adelyn and her family would drive eight hours for appointments with the endocrinologist who was supervising her transition along with a team of experts. A few days ago, they got a letter from the endocrinologist saying that they could no longer treat her. The doctor was moving to California, the doctor confided to the family, because of the situation in Texas.

As a family, they’re considering traveling to New Mexico or Mexico to seek medical advice that is being denied at home. Adelyn doesn’t want to live in Texas but her mother said that, unfortunately, moving is currently not a possibility.

Adamalis said that the medical treatment they were able to get up to now “has given us the best years of Adelyn,” but that now she feels afraid and helpless.

She asks politicians to “educate themselves on the issue, but more than anything, to focus on what the problem really is: immigration reform, getting better health insurance, gun reform.”

Trans children and adolescents “are not the problem,” Adamalis said.

‘It has saved our entire family’

Juan is going to be 10 years old and identifies as trans. Due to his age, he’s only experienced a social transition with the support of his family, who is of Mexican origin, and a medical team that includes psychologists and counselors. The family lives in California, a state that, unlike Texas, has passed legislation to protect the legal and medical rights of LGBTQ+ people.

Juan’s transition began three years ago, although “from a very young age, from a very young age, around 2 years old — he always identified himself as a masculine,” his mother, Grisel Soriano, told Noticias Telemundo.

The process, she said, hasn’t been easy. “We went through a very complex emotional situation … because we didn’t really understand what was happening,” Soriano said.

For two years, the family tried to find alternatives, such as taking refuge in religion, but “we really started the transition out of survival,” Soriano said, adding that at the age of 6 “Juan had already had thoughts of death.”

His clothes, his hair, his name, made him suffer, Soriano said. “He didn’t like the gender that we were forcing him to live in at all.”

The family, guided by a team of medical experts, has supported Juan, although his mother feels that as parents they are judged and recriminated by a society that doesn’t understand them.

“It’s difficult to understand a trans family. It’s difficult to understand a trans child when you do not have one at home … until we hear our children say that they would be better off dead,” Soriano said.

Soriano believes that there are many myths surrounding trans children and their families. “They judge us as if one day our children decided to be trans children and we say happily, we are going to help them … We went through a difficult process and we do it from affection, from love,” she said.

Families, especially parents, go through a process similar to the stages of grief: shock, denial, anger, negotiation and acceptance, wrote Jason Rafferty, a pediatrician and psychiatrist at the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Rejecting and suppressing trans minors won’t make them change their gender identity, Rafferty wrote, but it harms the child’s emotional health and development and possibly contributes to high rates of depression, anxiety and other mental health problems.

Nearly 600 anti-trans bills have been promoted across the country in 2023, according to the Trans Legislation Tracker‘s count. By contrast, only 19 bills were promoted in 2015.

Juan’s transition — he chose his name — “has been happiness for him,” his mother said. “After we started the transition, I saw him comfortable, I saw him happy, I saw him content … The transition has saved not only Juan, it has saved our entire family.”

Juan, whose favorite sport is American football, wants to be a doctor when he grows up. “I want to help children who are trans too,” he said.

He wanted to tell his story so that other children like him know that “everything will be fine.”