Indigenous transgender woman in Chile champions her communities

Being a transgender woman in South America is not easy when her average life expectancy in the continent is 35 years. It is even more difficult for those who are of indigenous descent.

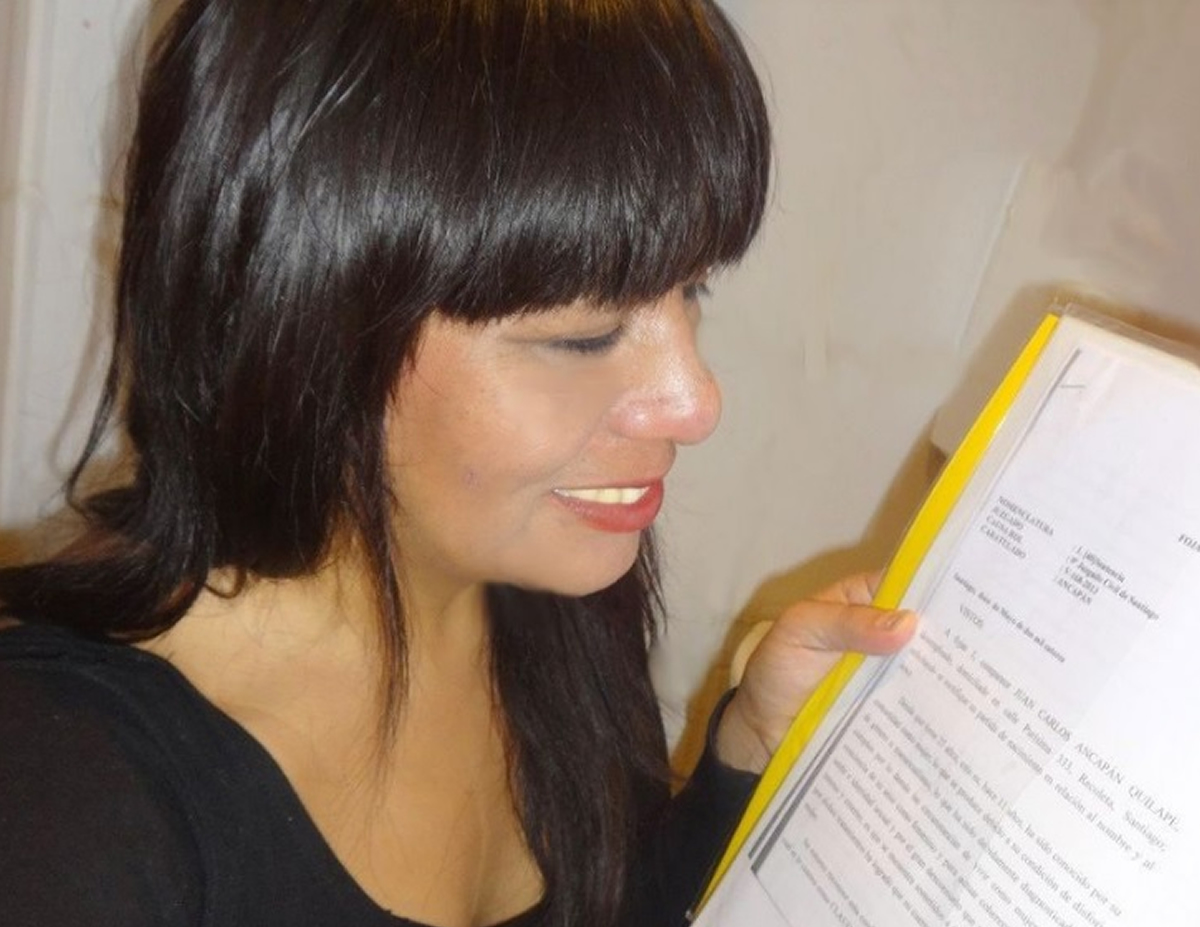

Claudia Ancapán Quilape, an indigenous trans woman with a Huilliche father and a Mapuche mother, has turned her fate around.

Ancapán is 46-years-old and lives in Recoleta in the Chilean capital of Santiago. She is a midwife who works in a private clinic and recently earned a master’s degree in health. Ancapán is working on another master’s degree in gender and will soon begin a doctorate in public policy.

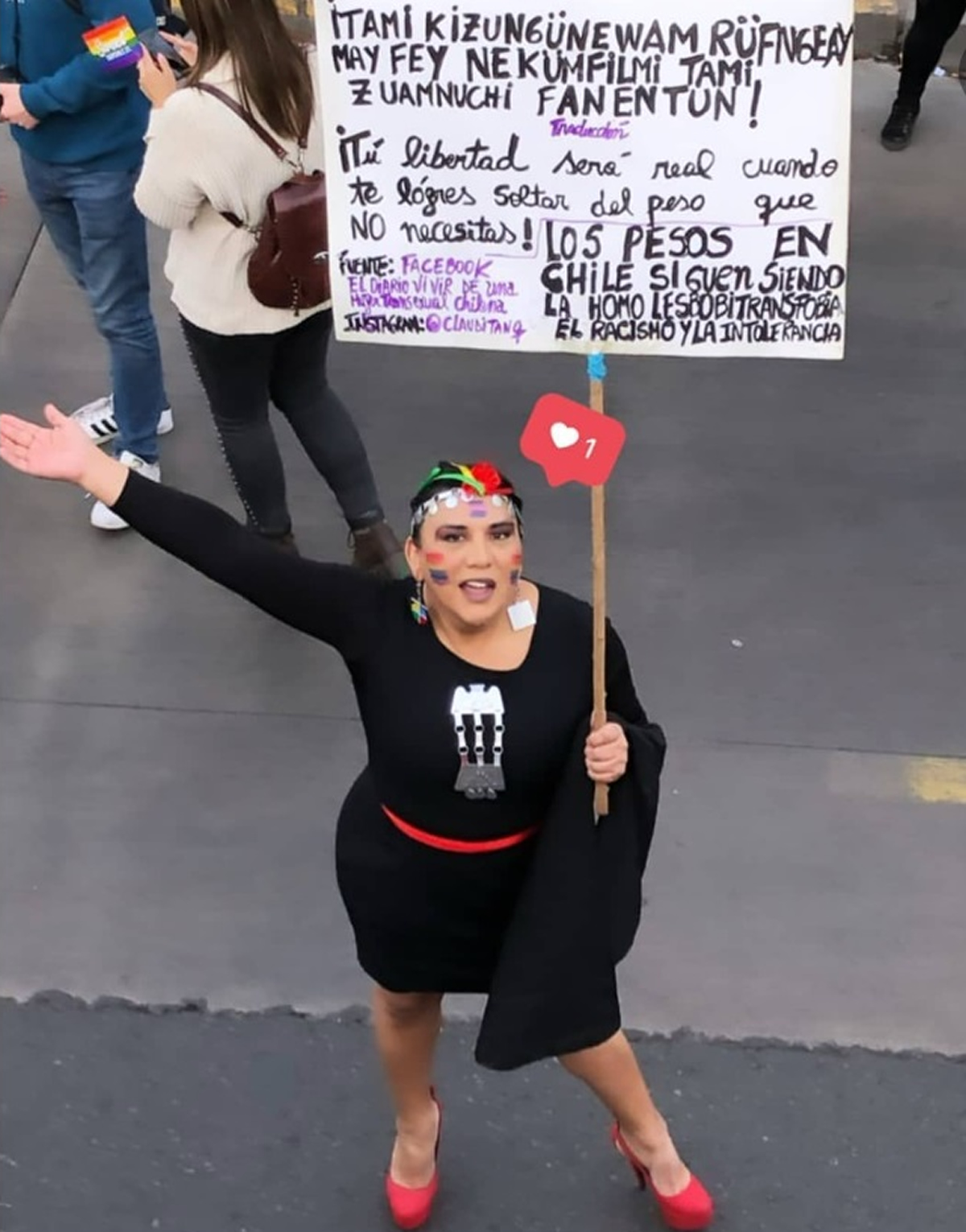

She is also a spokesperson for Salud Trans para Chile, a trans rights group, and participates in Santiago’s “LGBTQA+ Roundtable.”

Ancapán for six years fought to have her identity legally recognized, long before Chile passed its Gender Identity Law. She won that battle on May 20, 2014, and Ancapán later lobbied lawmakers to approve the statute.

The road on which Ancapán traveled in order to become a woman has been difficult.

“I am a person who has had to struggle with being a woman, trans and indigenous,” she told the Washington Blade.

In addition to the discrimination she suffered, a group of neo-Nazis in 2005 attacked her in Valdivia, a city in southern Chile where she was studying. The attack, which could have cost her her life, motivated her to become a queer rights activist.

Ancapán told the Blade her family’s indigenous culture allowed her to be herself in private since she was a child. Outside of her home, however, she had to pretend to be a man.

“My family allowed me to develop myself and that changed my life,” she told the Blade. “I was always a woman to my father, mother and siblings because my parents were not prejudiced against it. However, they protected me from society and I acted like a man once I walked out the door of my house because people outside our culture would not understand.”

Most indigenous groups in South America did not view LGBTQ people negatively before European colonization. They included them in their respective communities and respected them.

European colonizers exterminated many of them and buried their culture.

“Christopher Columbus arrived on his ship with religious cultural impositions that were imposed and everything was turned into sin,” Ancapán told the Blade. “If you review the history of our native peoples in Chile, they stand out because they had no conflict with homosexuality or gender identity.”

Since ancestral times there were “machis” called “weyes,” who had an important social and spiritual role within a Mapuche community. They were known for their ambiguous gender roles that could vary from feminine to masculine. “Weyes” could also incorporate feminine elements that had a sacred connotation and were allowed to have same-sex relations with younger men.

The “machi weyes” until the 18th century had a lot of authority and influence because they were recognized as a person with “two souls.”

“Pre-Columbian cultures saw the integrality of the human being linked to nature, so sexuality was an integral part of a whole (person),” explained Ancapán. “So it was not so sinful to fall in love or love a person of the same sex or for a person to present themselves with an identity different from the one they should have biologically.”

“That makes me respect my indigenous background,” she emphasized. “That’s why I am so proud of who I am and of my native belonging.”

According to Elisa Loncón, the former president of Chile’s Constitutional Constitution and a leading expert in Mapudungun, the Mapuche people’s native language, the Mapuche always recognized LGBTQ and intersex people through their language. Gay men were categorized as “weyes” and lesbian women were known as “alka zomos.” “Zomo wenxu” meant “woman man,” while “wenxu zomo” translated to “man woman.”

There is currently no indigenous LGBTQ or intersex organization in Chile, but Ancapán noted there are queer people who are indigenous.

“I know Diaguita people. I am also aware that there are trans Easter Islanders. I have Mapuche friends who are trans. And lately I made a friendship with an indigenous person who lives with two spirits,” she said.

Ancapán said two-spirit is “a category of gender identity that is not well known in Chile, but it is linked to native people.”

“In fact, they have always been there, but very little is known about it. This is related to the native peoples of pre-Columbian America, where they saw identity and gender as a way of life where they saw identity and the expression of sexuality as distinct,” she explained to the Blade.

Many people who claim to be two-spirit say they feel neither male nor female, escaping from the traditional gender binary.

“These manifestations are also in the indigenous peoples of Canada and Mexico,” said Ancapán. “They are known more in the north of North America. Two-spirit is basically spiritually associated, where two identities, two spirits, coexist in you. And that speaks of breaking down the binary system.”

“So these manifestations come from the integral vision of different sexuality and from the acceptance that existed in some cultures about sexual and gender dissidence,” she further stressed.

“I believe in nature and the power of the elements,” added Ancapán. “I am very close to my culture that talks about the connection with the spiritual of nature and the respect for nature. And from that point of view it linked me to my original people, to my native peoples.”