Writer Clayton Delery on Reconstructing a Hate Crime

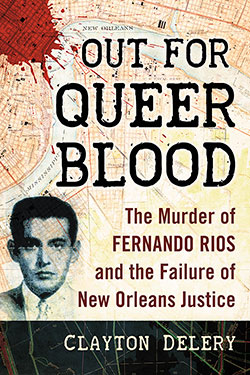

Clayton Delery’s previous book, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, was named Book of the Year by the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities in 2015. His new book is Out for Queer Blood: The Murder of Fernando Rios and the Failure of New Orleans Justice. It tells the story of an anti-gay hate crime that took place in New Orleans in 1958 and chronicles a time and place in American history where such a crime was inevitable. In addition, Delery is a contributor to collections such as My Gay New Orleans and Fashionably Late: Gay, Bi, and Trans Men who Came Out Later in Life. Clayton Delery lives in New Orleans, where he is currently working on a book which does not involve autopsies or homicide.

Tell me briefly about how Mr. Fernando Rios was killed.

In September of 1958, three young men who were students at Tulane University didn’t have anything to do one night, so they decided to “roll a queer.” They were going to beat up and rob a gay man, simply because he was gay. Today this might be described as a gay bashing, and the crime might be described as a hate crime.

One of the students, a man named John Farrell, went inside a gay bar known as Café Lafitte. He started talking to Fernando Rios, who was a professional tour guide visiting the city. Farrell and Fernando Rios spoke for somewhere between a half hour and an hour. Then Farrell offered Rios a ride back to his hotel. When Farrell and Rios left the bar, Farrell’s two friends joined them from across the street. Farrell led Rios into an alley, where he was beaten so badly that he died of his injuries.

What sparked your interest in Mr. Rios? Was your interest in this case purely academic or historical? Was “rolling a queer” a popular hobby for the youths of the day?

I thought my interest was purely academic, but late in the process, I realized that I had always identified with Fernando Rios. In high school, I was bullied fairly regularly. Some of the bullying consisted of verbal taunts, but some of it was physical. Things like being pushed from behind, or having my face shoved into lockers. I was always afraid it would escalate.

Those kinds of events—rolling queers, or harassing the gay kid at school—may not happen as often as they used to, but they haven’t gone away.

Mr. Rios was only a visitor to New Orleans. Was his family, if any, present for the trial?

His family lived in Mexico City, and they couldn’t afford to come to New Orleans for the trial. The defendants packed the courtroom with their relatives. Especially their mothers, sisters, and aunts. It had the effect of creating sympathy for the defendants, and the fact that Rios had neither friends nor relatives in the room allowed the defense attorneys to create any picture of him that they chose.

After the assailants were arrested and tried, they were acquitted by a sympathetic jury, and when the verdict for acquittal was announced, the courtroom erupted into loud and sustained cheers. Were you surprised by this spirited applause?

I was not at all surprised. City Hall and both the daily newspapers were on the side of the defendants. The men who killed Rios were being portrayed as the real victims, and Rios was portrayed as a foreign pervert who had threatened them. The killing was self-defense—their attorneys said—because he had made an “indecent advance.” The fact that Rios was Mexican made it even easier to turn him into the villain, because it was a period of intense anti-Mexican prejudice. In fact, there are even newspaper articles in which Rios is not mentioned by name. Instead, he is identified as “the Mexican.”

Please describe the process of retrieving and examining courtroom documents from the case. Were they easily accessible? What document(s) provided you with the most details? Did you have access to everything you desired?

I had access to a good number of documents. The case report filed by the New Orleans Police, for example, detailed what happened when Rios was found in the alley. Their report contained the statements made by the three defendants upon their arrest. The pre-trial documents filed by both the prosecution and defense teams were available, and so was Fernando Rios’s autopsy report.

I had access to a good number of documents. The case report filed by the New Orleans Police, for example, detailed what happened when Rios was found in the alley. Their report contained the statements made by the three defendants upon their arrest. The pre-trial documents filed by both the prosecution and defense teams were available, and so was Fernando Rios’s autopsy report.

Unfortunately, the transcripts from the actual trial were lost when the city flooded after Hurricane Katrina. Fortunately, both of the New Orleans daily papers covered the trial in detail, so it was fairly easy to reconstruct what happened in the courtroom.

Were you able to locate any of Mr. Rios’s family? If so, what was their response?

He would be eighty-six today if he hadn’t died. It’s possible there are surviving siblings, or maybe some nieces and nephews, but I was never able to locate any. I would love it, though, if one day I were to get an email or a letter from somebody who had known him.

Out For Queer Blood delves into the connections between anti-Latino prejudices, homophobia, and societal norms in 1950s America regarding “operation wetback.” How does that parallel with today’s society and the Trump Administration’s stance on immigration? While writing your book and watching the evening news or reading newspapers, how did it make you feel?

I spent several months reading newspapers from the 1950s, and then I would come home and watch the news and realize that many of the stories were the same. In the 1950s, newspapers described Mexican immigrants as sources of poverty, crime, and disease. I would read that, and then come home and see Donald Trump on television describing them as murderers, rapists, and drug dealers.

But the parallels went beyond the issue of immigration. In the 1950s, newspapers warned people that gay men were a threat, because they would molest young children in public restrooms. While I was writing this book, many politicians on the political right were claiming that transgender people were a threat, because they would molest children in public restrooms. In the 1950s, conservative politicians were trying to disenfranchise black voters through literacy tests. Today, conservative politicians are trying to pass voter I.D. requirements. They claim this is to prevent voter fraud, but on-site voter fraud is virtually nonexistent. The voter I.D. laws would, however, make it difficult for poorer people to vote, and those poorer people are disproportionately people of color.

Was there any difficulty writing this book compared to writing The Up Stairs Lounge?

The difficulty was emotional. As horrible as the story of The Up Stairs Lounge was, there were at least a few people courageous enough to speak out publicly on behalf of the dead and injured. When Fernando Rios was murdered, there was nobody to speak out for him. That left the press and the defense team free to describe him as a pervert and a potential rapist, and to claim that the three men who killed him had done absolutely nothing wrong. Indeed, it was implied that they had done a public service. And I found dealing with that part of the story very painful.

Your book launch was this past November and was hosted at Cafe Lafitte which is the bar where Mr. Rios met his attackers. Describe the night of your book launch.

It was a great night. The current management knew about the Fernando Rios murder, and that he had been in the bar right before he died. They were delighted to host the event. In the 1950s, the mayor was engaged in an official effort known as “the drive against the deviates.” He wanted to eliminate homosexuality from the city of New Orleans. Instead, New Orleans is now internationally recognized as one of the nation’s capitals of LGBT life. Rios was a victim of the drive against the deviates, but clearly the city’s LGBT community is winning the war.

In 2016, we were cohorts through the Lambda Literary writing workshop and studied nonfiction with Sarah Schulman. You workshopped Out For Queer Blood. What impact did that have on your book? How did you find your publisher?

Sarah Schulman is a remarkable woman and a very gifted teacher, so just being in a room with her, and with other talented writers, was a real blessing. She also was gracious enough to read my manuscript and comment upon it while I was getting it ready to send to the publisher. You and the other students in the workshop helped me realize what parts of the story—and New Orleans history—were common knowledge, and where I had to fill in background information.

As for how I found my publisher—well, my publisher found me. For years, I was writing one version or another of the Great American Gay Novel, and nobody was ever particularly interested. Then I started writing a nonfiction account of the fire at the Up Stairs Lounge, and an editor at McFarland heard about what I was doing and sought me out. Later, when I was nearing completion of a nonfiction account of the Fernando Rios killing, McFarland came looking again. So my advice to young writers who have a difficult time getting published might be to put the novel on hold for now, and consider writing nonfiction. There are lots of true stories out there that need to be told.