Religious trauma still haunts millions of LGBTQ Americans

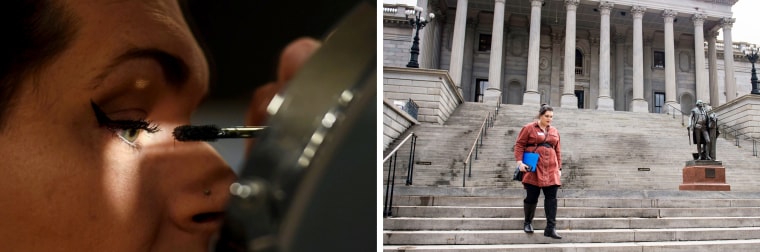

Experts say LGBTQ people experience religious trauma at disproportionate rates and in unique ways. Justin J. Wee and Evan Jenkins for NBC News

Kellen Swift-Godzisz, 35, said he doesn’t go on dates, struggles with erectile dysfunction and is hesitant to trust people. For more than 20 years, he’s experienced intense bouts of anxiety and depression that have had a “major hold on his life.”

“Imagine being told by everyone you trusted that you’re going to hell because you like men,” Swift-Godzisz, a marketing project manager living in Chicago, told NBC News.

At just 11 years old, Swift-Godzisz recalled, he would sit in his bedroom every night praying or writing letters that said, “Please God, remove my affliction of same-sex attraction,” and would then store each letter in an overflowing shoebox in his closet.

Swift-Godzisz, who grew up in an evangelical Baptist church in rural Michigan, believed Bible verses like Matthew 21:22 — “And whatever you ask in prayer, you will receive, if you have faith” — would help him “pray the gay away.”

As he entered his teens and realized his feelings of same-sex attraction were only intensifying, Swift-Godzisz finally accepted that God would not be answering his prayers. Things went downhill from there, he said.

Swift-Godzisz is among the 1 in 3 adults in the United States who have suffered from religious trauma at some point in their life, according to a 2023 study published in the Socio-Historical Examination of Religion and Ministry Journal. That same study suggests up to 1 in 5 U.S. adults currently suffer from major religious trauma symptoms.

Religious trauma occurs when an individual’s religious upbringing has lasting adverse effects on their physical, mental or emotional well-being, according to the Religious Trauma Institute. Symptoms can include guilt, shame, loss of trust and loss of meaning in life. While religious trauma hasn’t officially been classified as a mental disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), there is debate among psychiatrists about whether that should change.

Experts say LGBTQ people — who represent more than 7% of the U.S. population, according to a 2023 Gallup poll — experience religious trauma at disproportionate rates and in unique ways. Very little research has been done in this field, but a 2022 study found that LGBTQ people who experience certain forms of religious trauma are at increased risk for suicidality, substance abuse, homelessness, anxiety and depression. And as political animus toward the LGBTQ community intensifies ahead of the 2024 presidential election, many queer people say their pain is resurfacing.

‘It’s basically a mind rape’

The concept of religious trauma has been around for centuries, and, according to experts, it can have serious consequences that can last a lifetime.

“In its worst manifestations, it’s basically a mind rape,” said Marlene Winell, a psychologist who coined the term “religious trauma syndrome” in 2011. “These doctrines that are taught to you over and over are so damaging and so hideous and so hard to weed out. In many cases, you have been violated, you have been abused or you have been shamed, and the impact is very deep and can be everlasting.”

Dr. Jack Drescher, a clinical professor of psychiatry at Columbia University who specializes in LGBTQ populations, agreed, noting that growing up gay or transgender in a nonaccepting religious environment could have serious mental health consequences.

“When you hide or morph your behavior in an effort to conceal your queer identity, you wind up hiding other things about yourself,” he said. “There may be strengths or aspirations you have that you never access because you’re afraid they’re associated with your gender identity. This can affect your self-esteem, it can affect your confidence, and even your capacity to be realistic about what you can do and achieve.”

At 14, when Swift-Godzisz accepted that he could not “pray the gay away,” he confided in his youth pastor, who in turn told his parents and the entire church leadership.

“My mom was hysterical and ashamed and wanted us to pack up and move to a new town,” he said. “My parents very much viewed it as a sin and a choice that I made that we were going to fix.”

For the next three years, Swift-Godzisz said, he was grounded indefinitely. He said his parents controlled the friends he was allowed to hang out with and enrolled him in so-called conversion therapy, a discredited practice that aims to change a person’s sexual orientation. For this type of therapy, Swift-Godzisz said, his parents forced him to speak with various people from the fundamentalist Christian group Focus on the Family, which is widely known for its anti-LGBTQ advocacy.

“They weren’t trying to understand me,” he recalled of his sessions with the Focus on the Family leaders. “All of their advice was just, ‘Practice abstinence,’ or ‘Don’t do that; that’s against God’s wishes.”

While conversion therapy has been made fully or partially illegal for licensed mental health practitioners in 27 states and Washington, D.C., these laws don’t apply to religious leaders.

Swift-Godzisz’s mother, who declined to address her son’s allegations, told NBC News that while she and her son “differ on some things,” she would give her life for him in a moment. “I’m proud of my son, I love him and I’m glad the Lord gave him to me,” she said.

Focus on the Family did not reply to a request for comment.

“The church has been the villain in my life story,” Swift-Godzisz said, adding that he’s been traumatized by his family and religious leaders. “Anything I’d do that’s ‘gay’ was considered a sin.”

Now, decades later, Swift-Godzisz said he struggles with severe ADHD and — though he’s never been officially diagnosed — what he described as post-traumatic stress disorder, or “PTSD-like feelings.” He also said growing up queer in an ultrareligious household has led to persistent issues in his romantic life, including erectile dysfunction.

“When you’ve spent decades of your life reinforcing not getting a boner around another guy, and now even though you are ready to do that sort of stuff, your brain still kind of goes like, ‘I don’t know, we’re not supposed to do that,’” he explained.

He also said he avoids romantic relationships altogether.

“Still, to this day, one of my biggest fears is that I’ll get married to a man, have children and get old with him, and on my deathbed I’ll denounce it all because I’m afraid that I might go to hell,” he said. “So I just don’t do it.”

Winell said many of her patients’ trauma response is so active from what they experienced as a child that their brain gets confused about what’s past and what’s present, which causes the fear response to fire up in situations where they are doing something related to their sexuality or gender identity.

“Sometimes there’s a real split between what you think in your head — your intellectual understanding of everything — and your gut-level emotional condition and response to situations,” she explained. “So someone like Swift-Godzisz might be comfortable with his identity but can still have this gut-level fight-or-flight response in the amygdala to all the trauma from the past, and if that happens constantly, that can really screw you up.”

She added that people experiencing this can also develop physical symptoms like digestive problems and headaches.

The effect of familial and community rejection

Religious trauma for LGBTQ people may be particularly intense, because it “goes to the very essence of who the person is,” according to Winell.

“There’s so much condemnation in conservative kinds of churches about being LGBTQ, that the trauma is felt as a direct attack on them,” she said.

LGBTQ people experiencing religious trauma may also be met with instant rejection when they come out or when their queer identity is discovered, she said, noting that they could lose connection with family, friends, church leadership and other forms of community overnight.

“In a biological way, we all want to belong, and we are attached to our parents — we’re dependent on them and need their approval. So if you have their love growing up and then one day, boom, they reject you for something you can’t control, that can create long-lasting anxiety and trauma,” Winell said. “The icing on the cake is that you might simultaneously be losing friends, mentors or entire communities.”

Jamie Long, 40, is among those who quickly lost her support system due to a clash between her LGBTQ identity and her religion.

“Religion has obliterated my life,” she said.

Growing up in Greensboro, Alabama, where her father was the deacon and Sunday school teacher of her Pentecostal church, Long — who was assigned male at birth but now often uses she/her pronouns — remembers feeling different about her gender and sexuality as early as kindergarten. She spent her youth “in hiding,” doing everything to beg God to give her the power to change the feelings she had about her gender and her attraction to men.

“I would pray for hours nonstop,” said Long, who, decades later, is still trying to figure out her gender identity. “Nothing worked. It was terrifying.”

As time went on, it became harder for Long to hide her effeminate behavior. So she came out as a gay man and started hooking up with men on “the down-low,” which she said is omnipresent among men who have sex with men in the Black church.

“The pressure to subscribe to heterosexuality and masculinity is so intense, so there’s this culture in the Black religious community of guys keeping their hookups on ‘the low,’” she added.

As people close to Long started to find out she had come out as gay, the rejection ramped up. Her choir director — whom she described as a prominent figure she looked up to — pulled her aside after a Sunday service and said, “We can’t have a homosexual singing in the choir. I’m going to work with you to get that evil spirit out of you,” Long recalled. Her mom, who had been her “biggest supporter,” broke down in tears and said, “You will burn in hell,” and her brother berated her and called her anti-gay slurs for the duration of a 30-minute drive through Alabama, she recalled.

Long’s brother told NBC News that he “doesn’t remember” that car ride and — using male pronouns for his sibling — said that while he loves Long, he does not respect the path Long has chosen. “I don’t believe in gay; I believe it’s a spirit,” he said. Long’s choir director did not respond to a request for comment.

Now, years after losing most of her support systems because of her LGBTQ identity, Long has been diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder.

“I blame 100% of my identity crisis, of who I am as a queer person, on my religious upbringing,” Long said. “I had to create a mask and suppress my feelings all because of how I was brought up in the church. I was conditioned to believe my life was wrong.”

When religion meets politics

In addition to feeling isolated or rejected by family and community, many LGBTQ Americans say the current political climate is exacerbating their experience with religious trauma.

In 2023, a record-shattering 510 anti-LGBTQ bills were introduced in state legislatures, with more than 80 of them passed into law, according to the American Civil Liberties Union. Transgender people’s access to health care was a key talking point in the Republican presidential primary debates, and, before he was in Congress, recently elected House Speaker Mike Johnson called same-sex marriage a “dark harbinger of chaos” and suggested it could lead to people wedding their pets.

“For me, the religious aspect is almost inextricable from the political aspect,” said Amberlyn Boiter, a business analyst for a software development company, who lives in Spartanburg, South Carolina.

She remembers attending a 1,500-person megachurch just months before she came out as trans where the entire audience applauded after the pastor went on a 10-minute “transphobic rant.”

“I had to go up and play the bass in the church band after that, and I remember hating every second,” Boiter, 36, said.

Shortly after that, she came out to her family and they rejected her, stating that she was “betraying God and in turn she had betrayed them.”

“I think the biggest hurt is seeing our family members choose mythology over a relationship with their own flesh and blood,” she said.

Boiter cited the 20 anti-LGBTQ bills that were introduced in South Carolina’s state legislature in 2023. Some bills would strip trans people of gender-affirming health care, while others would criminalize them if they use public bathroomsthat match their gender identity. Many of the bills were backed by Christian legal groups and think tanks like the Alliance Defending Freedom, the Heritage Foundation and the Family Research Council.

“Being able to tie the policy to religious sources, it makes me feel doomed,” Boiter said. “There have been some pretty dark days, some of which have gone into the territory of suicidal ideation, where I’m worrying about whether I am going to have to uproot my wife and my child and move them from a place that I was born and raised.”

Boiter said she has ancestral ties in Spartanburg that go back to the 1780s.

“I have more than once spiraled into a place of thinking, ‘I might not only need to move to a different state, I may need to consider moving to another country.’ When people like Mike Johnson — who I would call a religious fanatic — are elected to higher and higher positions and even federal office, what am I supposed to think? More than a couple of times, I’ve looked at Canada’s refugee policies. I legitimately and truthfully worry that a day may come where my family and I are refugees.”

Swift-Godzisz shares those sentiments.

“I’m keeping the lid on a pot that is ready to boil over,” he said, adding that Johnson’s anti-LGBTQ track record is “one of the scariest things that has happened in my perception of politics.”

Healing from religious trauma

Mental health experts say in order to heal, those suffering from religious trauma should work toward building a new, affirming chapter in their lives.

Dr. Harold G. Koenig, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University Medical Center, said building that next chapter may involve cutting off those who hurt you.

“You say, ‘I love you, I forgive you,’ and you take the initiative to move forward. That will help heal you,” he said.

Koenig added that LGBTQ people who have experienced trauma but don’t want to leave religion entirely should consider joining an affirming church where leaders may be able to help with the healing process.

“Christian acceptance of [the LGBTQ] community is growing,” he said. In fact, majorities of every major religious group favor laws that protect LGBTQ people against discrimination, according to the Public Religion Research Institute’s 2022American Values Survey.

To move forward, Drescher recommends rebuilding self-esteem by forming new relationships. “It’s important to find new communities, new friendships that are affirming and that can help you heal,” he explained.

For those who leave their religion — as Swift-Godzisz, Long and Boiter have all done — it’s “like the rug gets pulled out from under you,” according to Winell.

“Your life needs to be gradually reconstructed,” she said. “It’s a reconstruct of who you think you are and what you believe now. One of those new beliefs is that being LGBTQ is OK.”

In terms of treatment, Winell said she first helps her patients learn to take care of themselves.

“Instead of outsourcing all that care to God, I teach them how to be self-reflective and how to regulate their feelings from their own perspective, rather than from the Bible’s,” she said.

From there, she teaches skills that help with the trauma response, like writing down negative messages you grew up believing and changing them to something that can read as positive and hopeful.

“What used to be, ‘My life is a trial, and then I die and go to hell,’ can change to, ‘My life is an adventure and a journey,’” she said.

She also works with her patients on relaxation by teaching them breathing exercises and body scan meditations, among other techniques. In certain cases, she recommends combining these tools with medication.

A debate among mental health providers

As more LGBTQ people share their experiences with religious trauma, there is debate among mental health experts about how it should be characterized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the American Psychiatric Association’s reference guide for coding, classifying and diagnosing mental disorders.

In the decades-old manual’s fifth and latest edition, the DSM-5-TR, religious trauma falls under the category “Religious or Spiritual Problem,” as a Z code, not an official mental disorder. Z codes are listed in the back of the DSM and are referred to as “other conditions that may be a focus of clinical attention.” Other examples include various forms of “Child Psychological Abuse,” “Unsheltered Homelessness” and “Victim of Terrorism or Torture.”

Koenig is now working with a group of public health experts and psychiatrists at Harvard University to expand “Religious or Spiritual Problem” as a Z code in the DSM to include “Moral Problems,” such as moral injury.

Moral injury, which is not currently listed in the DSM, may occur when an individual believes they have acted in a way that deeply conflicts with their morals and values, which produces guilt, shame or profound feelings of broken trust. It has been applied to war veterans and, more recently, to health care professionals who did not feel like they were able to provide appropriate care to those suffering during the Covid-19 pandemic.

“For centuries, people have been manipulating and weaponizing religion by condemning LGBTQ individuals,” Koenig said. “Moral injury — particularly for religious LGBTQ people — can create a whole life of shame and guilt. To live with it can result in mental health problems over time, like suicide, depression and anxiety, because that’s what moral injury does, and you can get stuck in it for years and decades.”

Koenig said it’s critical that the combination of “Religious or Spiritual Problem” and “Moral Problem” — which is currently under review by a DSM committee — finds a spot in the manual as a Z code. By adding moral injury, he explained, providers will be able to collect more specific data and prescribe more targeted treatments, such as whether it’s appropriate to recommend pastoral support for those suffering. They’ll also be able to more effectively document which part of the patient’s trauma came from their family’s or community’s religious beliefs and which part came from a separate worldview that being LGBTQ is immoral.

“For religious people who identify as LGBTQ, it’s not just Christianity at play,” he said. “It’s the whole moral fabric of the culture that’s been passed down through generations that has caused this condemnation.”

Getting a new disorder or code added to the DSM involves submitting an extensive proposal to the manual’s steering committee, which is then reviewed and forwarded along to the American Psychiatric Association’s board of trustees for approval.

“Having it as a Z code will validate and stimulate funding support, and then there’ll be more money for research, which will help us learn more about how we can treat folks experiencing moral injuries like religious trauma,” Koenig said.

A further step would be changing “Religious or Spiritual Problem” from a Z code to an official disorder in the DSM. While Koenig is unsure about his stance on this, as the process would be even more rigorous and could take years, Winell said she “definitely thinks it should be in there” as a disorder.

“Right now, most therapists don’t know much about it. They’ll do an intake with a new client and talk about family, schooling, substance abuse, but they won’t touch religion,” she said. “So if it was a real thing in the DSM, it would get covered and the millions of folks who are struggling with it across this country could get better help.”

Winell added that a disorder classification in the DSM would give religious trauma more credibility in the eyes of medical professionals and would give those experiencing this type of trauma the ability to name what they’re going through. She also predicted this would result in more research in the area and religious trauma becoming part of the curriculum in university psychology courses.

Drescher, who was part of the APA committee that in 2013 changed gender identity disorder to gender dysphoria in the DSM in an effort to remove stigma, disagrees with Winell on this matter.

“We don’t need diagnoses to understand what’s going on. … Medicalizing social issues is how homosexuality was originally labeled a mental disorder,” Drescher said, noting that homosexuality wasn’t officially removed from the DSM until 1973. “So the idea that now we’re going to turn anti-LGBTQ ideas into psychiatric diagnoses doesn’t sit well with me.”

This, he added, could enable a future generation to “just flip the switch” and pathologize homosexuality once again.

And while Drescher — who has been practicing psychiatry for over four decades — isn’t optimistic about changing the hearts and minds of today’s anti-LGBTQ church leaders who are “set in their ways,” he is still hopeful about the future.

“Younger religious people don’t think of LGBTQ people as their enemies. They know them as their friends, their neighbors and their fellow congregants,” he said.

“So as the new generation grows up, religious LGBTQ people will be met with greater acceptance rather than being stigmatized and having to hide who they are, and less hiding who you are means you can grow up feeling better about yourself and perhaps experience less anxiety, depression and other mental health struggles.”

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call or text 988 to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline or chat live at 988lifeline.org. You can also visit SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources for additional support.

Spencer Macnaughton is an Emmy-nominated and Gracie Award-winning producer and an adjunct professor at New York University, where he teaches journalism with a focus on LGBTQ issues.