Locked up in the Land of Liberty

I had never written a diary or narrated parts of my life before. I suppose this tradition of having a notebook with personal stories has been lost a bit, but I never thought my experiences were important enough to put them in writing. It would, however, be good for me to forget them. An unexpected turn in my journey through this world has nevertheless driven me to share even the most intimate episodes of my life.

That doesn’t mean that I have turned into a transcendental person, a kind of celebrity or influencer, but the events that I recount below are the results of one of the most heartbreaking experiences of my life. Thousands and thousands of other people like me have also suffered from them, but each of them has their own story.

These are my most personal experiences, my deepest feelings and frustrations that I felt during the more than 11 months that U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement detained me in American prisons as part of my petition for asylum in this country.

I fled my native Cuba because of the persecution that I suffered due to my work as an independent journalist. I was sanctioned, fired from Cuba’s official press and later persecuted by State Security, one of the dictatorship’s most repressive organs, with interrogations, intimidations, threats and bans from leaving the country because of my ties to foreign media outlets that cover the real Cuba.

This persecution is why I left my country in search of protection in the U.S., the country in which I entered on March 27, 2019, through a port of entry that links the cities of Mexicali, Mexico, and Calexico, Calif.

My transit through different ICE detention centers began on that day.

I spent a few days at the Imperial Regional Detention Center in California and a month at the Tallahatchie County Correctional Facility in Mississippi, followed by the Bossier Parish Medium Security Facility in Louisiana. I lived there from May 3, 2019, until Jan. 9, 2020. I had my court hearings, which ended with the granting of my asylum by an immigration judge on Sept. 18, 2019, in this jail.

I was then transferred to the River Correctional Center, also in Louisiana, and remained there until my release on March 4, 2020. I began to write these chronicles at Bossier with the simple goal of distracting my mind from the hell in which I was immersed. I was only able to put my thoughts in order and organize these portraits that are not only mine after I obtained my asylum.

These texts, written from inside federal, local and private U.S. prisons, are a compilation of other people’s lives that are shaped by tragedy, illusions, perseverance and by this unstoppable force of immigrants who, for many years, have made the U.S. a strong, prosperous and above all diverse country.

As incredible as some of these stories may seem, there is nothing in them that is fiction. I intended to be as loyal and honest as possible. Some people will perhaps identify with them. Others may be disillusioned, frustrated and even afraid, but nobody should feel indifferent.

Knocking on the door of the US (March 27, 2019)

I finally received the call for which I had been waiting a month. The Beta Group, a team from Mexico’s immigration service that coordinates the legal entry of immigrants to the United States, was talking to me on the other end of the line. My time to cross had come and they asked me to come as soon as possible.

I had come to their facilities on the bridge that divides the two countries several weeks ago to sign up for a waiting list. This is the only way for asylum seekers to go north in an orderly and safe manner. They wrote my name and phone number, along with thousands of others, into a very thick book that had aged from being used too much.

“We will call you when it is your turn, but the wait to enter may take a month or two,” the officer said at the time.

It was never my intention to scale the wall and illegally enter U.S. territory. That is considered a crime and I did not want to start my new life by breaking the law. I preferred to knock on the door and ask for the help I needed.

I was staying at the home of Betty, a Mexican friend who is the wife of my father’s friend for whom I had affection for a long time. Betty opened her family’s doors to me and she always looked out for me like a surrogate mother. She was the one who drove me that morning in her car to the Beta Group’s premises, where an officer was waiting for me. Two women and their small children were also there.

Access to the country was a trickle, depending on the capacity of U.S. officials on the other side of the border. They requested a certain number of people to enter each day and the Mexican officials called from the list they had made. My number was over 1,000. I don’t remember exactly, but I was in the fifth and last group of the day.

I said goodbye to Betty with a long, shaky hug. I also said goodbye to my father, who was hundreds of kilometers from here, to my family and to my boyfriend in Cuba and to Mexico, which had been my adopted home for a few months.

This goodbye left a bittersweet taste in my mouth, because my heart was torn. On one hand I felt as though I was doing the right thing, that I must run and save my life, but on the other hand doubt remained. My vision became cloudy and anguish permeated my thoughts because I was unsure and terrified. My pulse began to race as I walked away. The survival instinct nevertheless still managed to win the inner struggle.

Betty filmed the departure on her cell phone and sent it to my family, with whom she had talked for a few minutes while we were on the way to the border.

The officer led us to his American colleagues in a tiny office next to the immigration windows where they check passersby’s visas and screen residents or citizens who are entering the United States.

They sat me on a bench and we went one by one to a cell where they searched every inch of our bodies. They made me take off my shoes, which they thoroughly checked for any forbidden items. They folded them by the sole, put their hands inside them and turned them upside down. Back at the window they asked for my passport and asked me some basic questions. They measured my height and took my picture.

Before long I was taken to another, much larger, office on a second or third floor with more officers and more immigrants. The open space was divided into three sections: The first was for mothers with small children, the second was for women who came alone, and the third was reserved for men. I saw the two Mexican women with their little ones who had entered with me because the partitions were not exactly solid.

Each area had plastic benches, a television and very thin mats that covered the entire floor. It was a makeshift shelter with the most basic of essentials. A large glass window in front of me allowed the light in and let me see the landscape, which, by the way, was not very encouraging. I could see the border, covered with barbed wire, fences and surveillance cameras. A railroad access gate was just below the building and a part of the American city of Calexico that was not far away was visible.

A large room, where various officers, women and men, worked nonstop, was behind me. I had access to a bathroom with toilets, urinals, sinks and mirrors, as well as drinking water from a drinking fountain. Women with babies were given milk, wet wipes, disposable diapers and other amenities.

Officers from time to time called us for interviews or to take fingerprints. They took my fingerprints three times. The system was not very efficient, which made the officers uncomfortable and delayed the process.

The interviews almost always took place in the early morning, in the same long room where the officers fill out their paperwork. My interview was in the afternoon. It took several hours because the officer interrupted me at every other question and ordered me to return to my seat. He was apparently not very motivated to work.

His tone was somewhat aggressive, defiant if you will, at first. He claimed that everyone came up with made-up tales, sometimes nonsensical stories. He no longer believed in anything. I was quite scared, but I slowly relaxed when I proved to him the facts of my case were true. I showed him the documents I had that were evidence. He selected a few and attached them to my form.

I ended up helping him write my answers in English. He told me at the end of the interview that I was the first person he interviewed with a solid story. My story was apparently organized, eloquent and not made up.

I later heard an officer say that my case was a positive “credible fear.” I had thus passed the first test. That made me feel a little more secure and I was able to sleep soundly that night. I could hardly sleep the first night. The mattress was too thin and I was still shaking and scared.

I was hoping that I could be released soon. I kept thinking about the good experience that a relative and my boyfriend’s cousins, who had only spent one night in detention after successfully passing the interview on the bridge, had. The families that were with me in this place were quickly released. I saw them arrive after me and get released in a few hours.

The conditions weren’t actually as bad as I expected. Most of the officers were of Latino descent and treated us decently. Meals filled me up, some more than others. I had a huge burrito stuffed with potato, rice and artificial eggs for breakfast. They also gave us milk and juice. The rest of the food consisted of sandwiches and hamburgers and they served us chicken with salad, a kind of Caesar salad, for dinner.

The hours passed very slowly. I had no one with whom I could talk. I always find it a bit difficult to break the ice with strangers and I wanted to avoid any situation that could lead to problems or misunderstandings.

Several men and women, especially those who tried to take advantage of the American immigration system by presenting a false visa to enter the country, arrived each day. Most of them were Mexicans and they were quickly sent back to their country. It is the neighbor after all. Most were young and some had tried to enter more than 10 times. Chinese and Africans, in addition to Latinos from various countries, were with me.

People who came in before me were handcuffed. They were being led out of the office to an unknown location. They asked me early in the morning on my third day if I wanted to bathe. They gave me various hygiene products and access to a small shower.

I was later able to change my clothes and I felt refreshed. The effects of 48 hours without proper grooming were already beginning to be felt. I went to the bathroom and washed my face and armpits and I brushed my teeth in the morning with my index finger without a toothbrush and toothpaste. I learned a short time later that I would be transferred together with another immigrant with whom I had exchanged a few words. I was going to finally get out of this place, but just not to where I expected.

The prison in the desert (March 30, 2019)

I was led, shackled and handcuffed, into one of the Border Patrol vehicles, a kind of small bus that they use for trips along the border. Two officers transferred me and another immigrant. I had no idea where they were taking me. I was suddenly in the country, looking out at the city of Calexico through a barred window.

I arrived at a huge facility, an imposing block of brown concrete, a few minutes later. The scene absolutely took my breath away. It was a sober building surrounded by fences and surveillance cameras on a desert floor where there wasn’t much room for life. The sign told me that I had arrived at the Imperial Regional Detention Facility.

Once inside, they led me to a room with a few seats and toilets to begin our intake process. I looked through the glass and tried to interpret what was happening in the large office where the officers worked. An alarm sounded every so often. It was a clock located at the bottom of the glass that forced them to check us in and reset it for another inspection in about 15 minutes. More immigrants — Asians, Central Americans, Africans … — soon began to arrive.

They fed us, decent enough I must add, and made us wait for hours in that cubicle that was beginning to exude a smell that was not very pleasant. I tried to sleep on the floor by tucking some clothes under my head until they started calling us to begin the process.

They carefully inspected each of my belongings and made an inventory of everything I had. I was assigned a box with various toiletries and uniforms and shoes. They ordered us to go through the showers before proceeding further into the facility.

The medical check-up was the next step. I was answering the interview questions when I found one that was out of place.

“How do you identify yourself? Gay, heterosexual or transgender?”

The question took me by surprise. I asked if it was part of the medical interview, since it seemed like a total invasion of my private life. They said it was part of the questionnaire and that it was a “confidential matter.”

They said an officer would speak to me more deeply about the subject in a few days because I identify as a gay man. I must confess that I was a bit surprised and more scared than I already was.

They ordered us to line up and we walked, carrying our plastic bins through the facility that seemed to never end. I tried to figure out what was hidden behind each door or fence, trying to calm my anxiety. They divided us into different dormitories, located on both sides of a wide and long corridor. Mine was one of the last ones.

The thick door hid a dorm with dozens of immigrants of different nationalities. The two-story pod consisted of two main areas: The beds, divided into open cubicles with two bunk beds, and the common space where tables, two televisions, telephones, microwaves, showers and a desk for the officer were located.

I arranged my belongings as best I could on top of a first-floor bunk. I learned from some of my fellow detainees when I spoke with them that I had a few free minutes on the phone to be able to call my relatives. They hadn’t heard from me in four days. I was able to communicate with my aunt and uncle in Miami and with my friend and editor Michael K. Lavers in D.C.

The brief calls only made it possible to say how I was and where I was. It was an attempt to calm me down, to listen to a familiar voice that would keep me calm, more than calming me down. It was in vain.

I learned after several conversations how the immigration process was moving forward. The next step would be a telephone interview with an ICE agent. Theoretically called the “credible fear” interview, this contact with the agency official would determine if my reasons for requesting asylum are valid. I would qualify for parole, which would allow me to continue my application outside of government custody, if I was successful in the interview.

For that, the people who would receive me had to send letters of support to ensure that I would attend all of my immigration hearings and that I did not pose a threat to American society. According to some comrades, being Cuban put me in an advantageous situation and they assured me that I would be released after a few weeks, as long as I was not transferred to another detention center.

The news was not so discouraging and it brought me some reassurance, although many doubts and insecurities remained in my mind. I meanwhile decided to be positive to make those days more bearable.

Imperial is what one might describe as a fairly friendly immigration detention center: Decent food that ranges from meat to fruit; a spacious recreational field where we can go for a walk, play soccer, exercise on machines or simply sit in the shade of some tents for two hours every day.

There is a door at the end of the common dorm that leads to a small outside patio, which can be accessed throughout the day and where there is a basketball hoop and some metal bars for simple exercises. There is even a portable speaker for playing music. The atmosphere on the facility’s screened terrace can be very festive. Reggaeton sometimes serves as a soundtrack for soccer matches or simply for those, like me, who just want to see a blue patch of sky or fill myself with the fresh air.

Inside the rough rectangle (April 1, 2019)

The day starts at 6 a.m. The call for breakfast turns on the lights and a line of sleepyheads prepares to receive the first meal of the day. Most have breakfast and then go back to sleep. Calm once again reigns before long; although a chorus of snoring, whispering or prayers in an unknown language can be heard at times.

I decide it’s time to leave my bunk when the sun peaks through the dorm windows. The toilets — each with walls and doors — are right next to the sinks. Communal showers are in one corner of the dorm. Small side dividers barely cover the most personal parts of those who bathe. It had already been recommended to me that I use the two showers on the second floor that have much higher curtains and dividers.

The detention center was very similar to the ones I had seen on the internet when I searched for information about the asylum process and the prisons in which immigrants are held. My mind at a minimum needed to have a reference to calm my many fears. I now live in one of them; a rough rectangle with sad walls, furnished with iron and surrounded by a musty atmosphere that suppresses the desire to smile.

Even so, there are those who manage to reduce their sadness and face the day to day with a winning spirit. I try to adopt that attitude, which is also a constant request from my family. I distract my mind as much as I can with various activities in search of that positivity. The Imperial Regional Detention Center has a library with books, magazines and newspapers in several languages and computers on which we can work on the documents needed for the asylum process.

The officers at different times each day call us to visit the library. It is a time of day to which I look forward, because reading sometimes manages to evade boredom and tension. The library has tables and chairs for reading in the room and there is the possibility of checking out books to read in the dorm. Religious volumes, self-help and some world literature books dominate the shelves. I decided to take “El general no tiene quien le escriba,” a short novel by Nobel Prize winner Gabriel García Márquez.

The librarian works in a latticed cubicle. From there she took my data to check out the book and printed various documents that a comrade sent from a computer. The man was filling out a form with questions, but I did not dare to ask further for fear of being indiscreet. The library, as is the case in the outside world, is an underappreciated treasure. For me it is instead the instructive escape against the useless hours of the day.

Another of my favorite places is the patio, an extremely spacious outdoor area where several dorms converge. Behind the double fence there is a lonely road, as if the cars did not want to look out there either. I stop at times to observe the light traffic. I keep my eyes on each of the few vehicles until they disappear on the horizon.

There are many people in the yard today for recreation. Some have organized a soccer game, others are lifting weights. Some are sitting at tables under the tents playing cards or just catching up. I walked laps around the entire field with a Nicaraguan with whom I have become friends. He has explained to me how many people work here and especially what the rules are for homosexuals.

He has explained to me they place people who identify as gay on the dorm’s second floor, where there is better lighting and the cameras can see things better. We are not allowed to bathe in the communal showers on the first floor. All of this, he tells me, is to avoid any kind of sexual attacks or assaults. Those will be the instructions that the officer will give me, who has already ordered my change of bed. My new bunk mates are Hindus. We managed to communicate in primitive English. Words in Spanish and Hindi slip through.

There are several people from India, as well as from Asian and African countries, in the dorm, although the bulk of them come from Central America and Cuba. I have not yet noticed any conflict in this mix of cultures, although I have only been here for a few hours. Those who have been in this jail for months must probably have a different opinion.

My Nicaraguan friend has suggested that I work in the kitchen. Immigrants here have the possibility of doing a variety of tasks, although cooking is one of the most coveted jobs. I enjoy cooking — and eating a lot, I’m not going to deny it either — so much, so it seemed like a fantastic idea. Besides clearing my mind, they’ll pay me $1 a day. The man who manages a small group of bakers who bake the bread every morning also lives in my dorm. Your pay is deposited into your personal accounts.

They explained to me that we all have an account. They deposit into it the money that we brought with us or that our relatives send to us through a web page. I have not mastered the mechanism very well. Everything is still very confusing. I will be able to order food and some items at that store they call the “commissary” when the money is available.

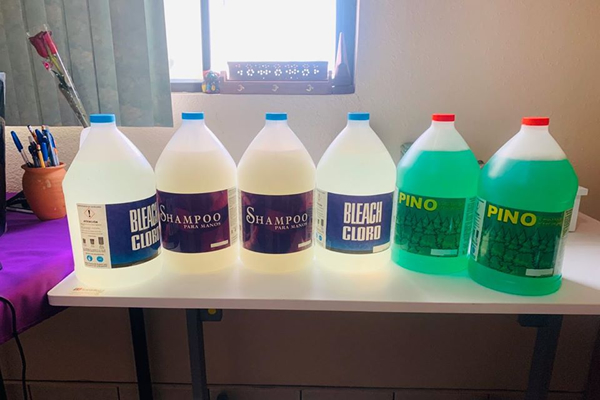

I never expected the jail to have a “supermarket.” The shopping list is made by marking the desired items on a printed document available at the detention center. There is a bit of everything: From candy to personal hygiene and office products. People order instant soups, sweets, coffee, chocolate and anything else that can improve their daily diet. Orders are collected twice a week and they arrive twice a week.

I must add my name to a list kept by the pod officer to get access to razors. They are obtained through a barter: The razor for the ID document. I must return it in perfect condition with all the metal blades in place once I finish shaving and they will return my card. I did not understand the reason for that rule at first, but they later explained to me that it is a security measure. The razors’ sharp blades can be turned into the perfect weapon to attack someone or used for self-harm. That idea, which had never crossed my mind, awakened a state of alert in me. It was like a jolt so I wouldn’t forget where I was.

A flight on ICE Air (April 5, 2019)

From my seat inside the bus I could hear the noise of the engines of the plane that was still parked. I could make out in the distance the airport with its usual bustle of airplanes. I was, however, in a secluded area that no one could see clearly. This area is accessed through a kind of back door, a gate with huge bars, which is probably used for other purposes.

It is a strategic, well thought out positioning. Handcuffed men boarding a plane at dawn is a very curious scene, and that’s the last thing ICE wants. Discretion in a procedure of this magnitude is essential.

Two more buses were parked around the plane. A line of immigrants left one of the buses and boarded the plane. We all anxiously looked for a gap in the windows that would let us see what was happening outside. We waited for several minutes before our turn came. I should only leave my seat when I hear my name.

“Valdés González, Yariel,” the agent yelled and my name caught in his mouth, as if he didn’t want to come out.

The shackles around my ankles create an arrhythmic concert of metallic screeches on the way to the plane. The roar of the turbines indicates the transfer’s urgency.

I have to go through two checkpoints — they searched my whole body in the first one in search of something inappropriate and they examined my mouth in the second one, as if I could really hide something threatening there — before boarding. I felt like an extremely dangerous convict.

I walked, watching my steps like a baby who still has a hard time standing. I climbed the steps of the plane slowly, one by one. It is not a huge airplane, but I would say that it has a capacity for approximately 200 people. Officers indicate available spaces on either side of the narrow aisle. I have a window seat on the right side of the plane, very close to the wing. A free flight and sightseeing. What a thrill!

There is a Hindu man next to me. He is wearing a striking turquoise turban. We exchanged timid greetings while the rest of them settled down. The flight attendants were wearing ICE jackets and appeared restless. The plane is full. There are very few open seats.

I launched into some prayers asking for protection before takeoff. I am basically afraid of a plane crash and I asked my saints to protect me in an attempt to calm me down. I don’t know why the religious side comes to life whenever I get on a plane.

The trip becomes monotonous after the exciting moment of takeoff and the initial curiosity of seeing the earth from the sky. The clouds with their thousands of shapes are all I can admire out the window. I lean my head to the wall of the plane trying to rest. I did not get a deep sleep, as anxiety and nervousness conspired against my peace of mind.

They gave us a bag with the same food from the bus and I managed to feed myself a little with the same clumsiness of handcuffed hands. Those who need to go to the bathroom are escorted by an officer to the plane’s tiny lavatory. The handcuffs were not removed at any time during the flight. You have to figure out how to deal with any eventuality.

I would say the flight was longer than three hours. I had no way of knowing exactly how much time passed since it began, much less any clue that told me where we were going. I looked out the window and the ground no longer seemed so far away. They indicated through the PA system that we will arrive at our destination shortly, without clarifying what the destination is.

The city before my eyes revealed itself as gray, drenched by a vigorous storm that will make our arrival even more strange. I once again said my prayers as we made our final descent. They seemed to have been heard when I felt the impact of the landing gear on the wet runway. We landed safely in a desolate airport and stopped on the tarmac with other planes that looked like toys because they were so tiny.

The surrounding buildings disappeared at times because the rain lashed so fiercely. The downpour was not a sufficient excuse to delay our extraction any longer. I ran as fast as the chains on my feet and the constant fear of slipping would allow me. I was drenched from head to toe when I boarded the bus. An officer then indicated that I should sit in the narrowest of the seats, which were in the back of the bus right next to the bathroom.

I was practically sitting on one of my legs and I fell on top of the person next to me every time someone opened the door to the tiny bathroom. More than 10 hours of travel had passed, so a visit to the back of the bus was imperative, including for me. The urine gave off a smelly odor from that cabin, and my nose was its closest victim.

I started to sweat. The ventilation was nil because the incessant torrential rain kept the windows closed. We would have been mercilessly drenched if I opened them, if we opened them, even a little bit. I fell prey to several episodes of anxiety on board that hermetic capsule. I was perhaps not the only one because around 40 immigrants were breathing the same thick, hot air that had apparently been recycled.

I arrived at my final destination approximately 12 hours later. The transfer included transportation by land and air and it had to be a long way from California, perhaps in some state in the middle of the country, but it was not yet clear to me. Signs on the road announced the names of totally unknown rural towns. We were again in the middle of a lonely place, secluded like an intruder. The landscape was not as arid as it was in the California desert. The same horror, nevertheless, overflowed.

Tallahatchie: A city behind bars

I was finally able to rest in what will be my new home — a tiny cell where there is only room for a two-story bunk bed, a toilet, a sink, a mirror and a sturdy door that separates me from the rest of the world — after they booked, photographed and properly located me. Our only view of the world outside of this dungeon after they close it is through a small hole that allows the officers to keep an eye on us from the hallway.

The beds, fixed to the wall, occupy the back of the cell, where a thin, upright rectangle provides a greatly reduced view of the outside. It is a kind of window sealed with a transparent material that barely allows light to enter and lets you see the courtyard and part of the M Building.

The toilet and sink are made of polished aluminum. The mirror, made of fake glass, gives me a blurry and distorted image. I was scared the first time I saw myself. I thought my face had mutated from so much stress, but no.

Gray plastic boxes under the bunk served as my wardrobe. I have put into them one of the two dark green uniforms, white sweatshirts, two pairs of underwear, two pairs of socks and a towel worn from so much use that it barely dries my body.

Some mini-tables are bolted to the wall, and that is where I have organized some of the personal hygiene products that they have given me: A bar of soap, a tube of toothpaste, a toothbrush so small that there is barely any place to hold it and a container with liquid that must be a master formula of cosmetology because it works as shampoo, bath gel and shaving cream.

I put that formula on and blood stained my face after my first shave. The razors have left me with wounds all over my face, even when I was extremely careful. I managed to stop the bleeding after a while by pressing the cuts with toilet paper. I recovered my original color.

My room is on the jail’s second floor with about 80 identical cells. They lock us up every night to sleep and several times a day for more than an hour to count, which is done in all units at the same time. The officer in charge of the pod does the first count; then a second officer verifies her colleague’s number and reports it to headquarters through a walkie talkie. They will reopen the doors if the numbers are correct.

My new home, the Tallahatchie County Correctional Center, is located just outside of Tutwiler in the state of Mississippi. It is an imposing fortification of several buildings, with three pods inside each of them. There are approximately 100 people inside each one. My building is identified with the letter “J,” which in turn is divided into JA, JB and JC. I live in cell 76 with another Cuban.

Tables on which to eat, telephones, four televisions, some strange machines through which commissary products are ordered and communal showers are in the common space. Three plastic curtains cover the entrance to the bathrooms at the end of the pods. There are an average of three showers, which pour hot water under pressure, in each of them. I sometimes feel like the main character of one of those prison scenes where the officers spray torrents of water at the prisoners, scrubbing them as if their bodies were made of metal.

The curtains between each shower try, without success, to create a personal atmosphere. I have located the “most private” showers after several days. They are almost always available around 1 p.m., when I can bathe practically by myself.

There are very few moments of privacy in this communal life, although it is not recommended to abuse solitude because depression and anxiety ensue. The prison library has been an effective antidote in this psychological battle. Books have become an oasis of distraction and culture amid so much lost time.

Each pod has an assigned time to visit the library. We reach it after walking around several buildings, escorted by an officer. It is not a very large room, but it is one of the few places that does not remind me that I am in a prison. The bulk of the books on the shelves are in English. I was, however, naturally able to find a significant number in Spanish.

Literature by Vargas Llosa, by Wendy Guerra, an exiled Cuban writer, and other lesser known writers as well as various magazines and newspapers complete the selection. We are able to take a single book to the cell to read for several days. They don’t give us much time in the library. We return to our cell after we have checked out the books that we will take with us.

The walk is short, but at least fresh air enters my lungs. Tallahatchie is a stately jail in the worst sense of the word. I sometimes feel that I am in a city behind bars with hundreds of souls whose only crime has been to come to American soil for help.

The buildings, which are connected by roads and dominated by towering barbed wire, look like sturdy blocks. Those who have somehow broken the laws of this country remain in some of them and this is their abode of penance. They never mix us. I only see them from my cell in the recreation areas.

They wear white and orange striped jumpsuits. Some work out on weight lifting machines, others walk the perimeter again and again and some try to erase the boredom of the confinement by exposing their naked torsos to the sun. I keep my eyes on a muscular man who runs laps while he listens to music with headphones. I don’t think he can see me through my tiny cell window.

I admire him and envy him at the same time. At least he knows how much time he has left on his sentence.

The gay JC troop

I began to connect with the gays in my dorm after a few days. I did not relate to them much at first. It is sometimes difficult for me to “break the ice” in social matters, especially in these circumstances where I interact with people from different cultures. I maintain only a certain closeness with my cellmate, a heterosexual Cuban in whom I do not have much confidence.

There are only three members of the JC pod’s queer troop: Britany Nicole de Castillo, a transgender woman from Guatemala, Darwin Celing Portillo, a gay man from Honduras, and myself. The group is small, but rich in stories and personalities.

Britany is as stunning as her name. She has a boisterous, uninhibited and warm character. She always laughs out loud, scaring away her own sadness and that of those around her. At 33-years-old, she wears her hair down to her shoulders, the only feminine feature the officers have not been able to remove. ICE does not consider her a woman simply because she does not have a vagina.

Immigration authorities don’t care about her gender identity, so they have registered her with her male name. She has been placed in a men’s dorm, dressed as a man.

Darwin is a young Honduran who entered this country with his younger brother and his boyfriend. They were separated at the border and he is now not sure where his brother was transferred. He learned through a relative with whom he infrequently speaks that his partner is in Colorado. News comes through third parties, since communication between arrests, as we have been told, is not allowed.

The small family’s separation from him keeps him depressed and sadness is plastered across his face. He is afraid of the night, because his worry often prevents him from falling asleep. I always greet him at noon when the gay squad meets up because mornings are almost always too early for him. We play cards or dominoes, watch television or simply chat in a cell trying to erase the endless hours.

I learned through our talks about their lives, marked by such aggressive homophobia that they were in danger on more than one occasion. Britany was shot three times in her lower limbs. She pulls up her pants to show me and there they are, irrefutable proof of transphobia. She has been beaten, threatened with death and has received countless verbal attacks, including from the Guatemalan police itself, as if she hadn’t been through enough.

Britany’s physical wounds have healed, but her psychological ones remain open. She decided it was time to end the horror and find a place where being herself wouldn’t put her in danger. That is why she crossed the border a little over two months ago. Her arrival in the United States has brought new traumas, such as being handcuffed as a lethal threat.

Britany told me that she first wants to recover physically and mentally, because “this process hurts you a bit and then work to get ahead and be free at last, without anyone discriminating or attacking me because I am who I am.”

The same desire prompted Darwin with his boyfriend and his brother to present themselves to immigration authorities at the U.S. border. He suffered the discrimination that still exists in Honduran society, the persecution and the violent harassment that gangs inflict against the LGBTQ community.

Darwin also has a scar on his right hand from when several gang members cut him with a broken bottle in an act of hatred that he will never forget. He was also beaten, threatened with death, and they violently broke into his apartment in the city of San Pedro Sula, although by then he had already fled.

Both have wanted to share their stories with the Blade. They feel the need to denounce the horrors through which they have lived and those they suffer right now for trying to save their lives in this country. I hope to send these interviews, which have helped me to understand and admire them much more, to my editor soon.

Homophobia, fortunately, does not exist in the JC immigrant community. Darwin previously reported his former cellmate after he insulted him on several occasions. The assailant was transferred to another dorm and now lives with a very nice Chinese man who shares with him everything he buys at the commissary.

As good friends we also share lunch and dinner. We season the tasteless salad together or add mayonnaise and ketchup to the pasta they give us each day. We give each other food or do swamps with each other, because sometimes someone likes something the other one doesn’t. We always share with those who throw anything away as a gesture of solidarity.

Britany has found other “companies” outside of the gay troop. She has told us about her sexual adventures in the brief intimacy of showers or inside cells. She has given blowjobs between the bathroom curtains. She has indulged in passionate kisses and fondling, many of which have ended in a thick white climax. Several comrades have succumbed to their most carnal desires and have found in Britany the ideal solution to alleviate forced celibacy.

Britany is complacent and calls each of her conquests “her boyfriend.” Darwin and I die laughing at her exploits and keep the “weakness” of her suitors a secret.

My ‘baptism by fire’ (April 11, 2019)

A paper attached to one of the pod’s doors announces the days and times for washing clothes, the commissary and recreation outings. Visits to the “yard” have so far been every day and for about an hour. It is right in front of my building. I can see from my cell’s tiny window when other pods come out to take in the outside world.

It really is an esplanade divided into two exactly equal sections with a few weightlifting machines, a basketball court, and a few bathrooms that few will dare to use. There is a wooden hut right in the middle where an officer watches our every move. Some form soccer teams, others compete to shoot the basketball in the hoop, while a small group is dedicated to walking or sitting on the ground looking for the sun to caress them with its warmth.

We will hopefully leave at the same time to go to another shelter in the neighboring part of the courtyard. We exchange stories, emotions when we meet someone from the same country through the bars that separate us. These talks, more than anything, are the ideal time to find out what the next step in the process is, how much time we have left in this hell and a thousand other questions that arise when we talk with immigrants who have spent more time in this prison.

The “credible fear” interview is the next test I must pass from what I’ve been told. It is a telephone conversation with an ICE officer who will determine if my fears of returning to my home country are true and in line with asylum policies in the United States. No one has been able to tell me precisely what happens after having successfully passed that interview or not.

Some wait several months for a transfer and others simply remain in a limbo where uncertainty is the only sure thing. The average waiting time for the result is about a week, but everything with ICE is very uncertain. They say that the first answers to arrive are always negative, so in this case it is best to wait a few more days.

I thought that I had already passed this interview, because an official at the border a few days ago had determined that I had a “credible fear” and filed some of the evidence that I gave him with my case. I am apparently wrong.

I began to psychologically prepare myself for that moment. I relive in my mind the events that marked my decision to flee Cuba in order to put my thoughts in order and in a coherent way when I report it to the ICE officer who I will have on the phone. They called the first group to interview a few days later.

The officers at around 7 a.m. opened some of the cells with a list in hand. My mind gets restless every time I see a list, because in this world they are almost always the prelude to changes that are not necessarily good.

They took several comrades, but I was not sure that they had been interviewed until they returned several hours later. I wanted to bombard them with questions, but they were still nervous and could not give precise answers that would help me clarify my doubts. No one was sure if they passed it. My nerves began to worsen. The next test was already very close.

The next day they made a second call. My heart stopped for a moment when the cell door opened shortly after dawn. They called my cellmate, who jumped off the bunk. I shook his hand and wished him all the luck in the world. I couldn’t sleep anymore. I will be the one to cross that door tomorrow at the same time in order to face another test, the last one if I am lucky.

I am living at an emotional crossroads right now. On the one hand, I want this to end as soon as possible, and the interview is the obvious way to do it, but at the same time I am in constant fear, which makes me wish it would never happen. I subject my countrymen to a second interrogation when they return, trying to calm my terror. I can’t do it. On the contrary, the nervousness grows worse, like an avalanche of snow that grows larger as it descends down the slope.

The tension, unbelievably, didn’t stop me from having a comforting sleep. After breakfast I get ready for the big moment. There are fewer hours left for my time. We must be in full uniform, with shoes on and as presentable as possible, or so I think. The officer pronounces my name and with the same sobriety she adds: “entrevista” or “interview.”

It is the last group in the pod. About 20 of us walk one behind the other like exemplary children, without talking very much. I see the tension in each of my comrades’ eyes and I feel mine stuck in my head without being able to escape. We left the dorm and entered another building. We walked down long corridors until we reached an enclosure where we could see the door inscription that read “hotel.”

The place is very similar to my pod, although smaller. The walls’ dark green color makes the cell at times a much more gloomy, depressing place. We are a few dozen immigrants from various shelters for whom the next few hours will be a defining moment to survive this process.

The officers in charge begin to give instructions. I understood the essence of them, but with difficulty because I am not used to this area’s accent. As we hear our names, we go inside one of the five cells. There is a telephone inside that we must answer when it rings. The ICE officer with an interpreter, who will facilitate communication in our native language, will be on the other end.

It’s my turn a few hours later. They first tell me to sit in a plastic box just behind the last cell. There is one outside each cell.

“You enter when the person inside is finished,” the officer ordered me.

The anxiety inside me grows like a Birthday balloon, ready to burst at any moment. I try to compose myself as I enter the “phone booth.”

The cell is much more elegant than mine, although identical in dimensions. The bunk beds are wide and the mattresses do not let you feel the metal surface on which they are supported. It must be wonderful sleeping there. I wonder what kind of prisoners deserve such comforts. Obviously not the immigrants. The sink and the toilet stand out in this scene for their white color. It is like a reminder of home to have that pottery inside that cell where no one resides.

The phone remained silent on a small table. I spent the minutes in silence, just with my impatience. I’d been waiting for the call for several minutes, but the phone was reluctant to ring, as if it wanted to punish me. No matter how much I expected it, no matter how closely I looked at that black device, its ring terrified me.

Two female voices on the other end of the line spoke to me. The first one belonged to the ICE officer and the other to the interpreter. It was a bit strange talking to those voices without a face, without a personality. I had to divide my answers into short sentences to allow enough time for simultaneous translation. The officer, with a pleasant but firm voice, made the interpreter swear that she would translate my statements as accurately as possible to the best of her abilities and that everything said in this interview had to remain confidential.

The translator explained the purpose of the interview was to determine if I might be eligible for asylum or protection from deportation to my country where I could face persecution or torture.

I tried to answer the officer’s questions as clearly and precisely as possible, although there were times when nervousness made my memory fuzzy. I denounced the situations that I experienced while working in the island’s state-run media and, with greater emphasis, the harassment from Cuban State Security agents because of my work as an independent journalist.

I confess that it was not easy to condense two years of persecution and surveillance by a dictatorship that feels threatened by your work, but the interview, more than anything else, became tiresome when the story brings you back to feelings that you thought you had overcome. The short breaks for the translation helped reduce my anxiety and get to the end without an emotional breakdown.

I asked about the interview that had been carried out on the bridge and the documents that I had delivered before we ended. The officer, however, said that she did not have any file with such documents, nor did she confirm whether I had survived this “baptism by fire.” She might as well have been dead after this phone “crossfire.” The officer’s voice, however, remained in the same tone the entire time. She did not reveal any hints of “victory” or “defeat” after we spoke for about an hour.

I felt lighter, like you are suddenly free from an excruciating weight after you carry a load on your back, when I hung up. The waiting room outside was still busy. Some talked in small groups while others sought to focus alone. I felt my body lose heat within a few minutes. I rubbed my arms with my bare hands in an attempt to find warmth, but to no avail. They brought me to the pod along with other comrades who had also finished their interview after we had spent a while in that refrigerator.

Experience dictates that the answer will arrive in a week or a little more. My stress levels dropped a bit over those days. There was no longer anything I could do to improve or hasten the result. Waiting, praying and trusting was the only thing left and so that’s what I did.

The door opened one afternoon while I was locked in my cell during one of the many daily headcounts. An ICE officer called me and asked me to sign a document. I asked what it was about and he said it was the positive result of my “credible fear.” interview. I scribbled on the paper and I could not contain my emotion. I felt palpitations, I wanted to cry, to scream, to jump, to run … ICE also gave me the English transcript of my interview and some documents that affirmed that I have the right to “parole.”

Parole or “conditional release” is granted to asylum seekers who passed their “credible fear” interview and surrendered to immigration authorities at a port of entry. Applicants must pass an interview in which they must present one or more “letters of support” from those who will receive them in this country and promise that they will attend their future immigration appointments. We must also prove that we are not a danger to the community. This benefit allows immigrants to continue their asylum process in freedom.

My interview was to take place in two days, which meant I had only 24 hours to gather all the necessary paperwork and send it to the officer who would conduct my process. I called my family in Miami and tormented them with everything they had to send, because my freedom depended on it. My uncle promised to prepare the papers and fax them to the officer because it was the fastest way to receive them.

The day and time came and I was never called for my parole interview. I instead received another document, this time to inform me that my parole had been denied. Just like that. The illusions fell apart in an instant and I once again began to see everything dark. Unjust confinement would continue, only in another jail. I only knew two initials of my new destination: Louisiana.