A Cry for Freedom: Exploring the Castro’s Gay Migration

The California Migration Museum recently launched a free, immersive audio tourwhich explores how an era of migration to the Castro transformed a sleepy Irish Catholic enclave into a queer homeland. We interviewed Gabby Santas from the project to learn more about the process of creating the tour, and how our archives played a pivotal role in shaping the content.

Tell us a bit about the Castro tour.

Gabby Santas: At Home in the Castro – our audio tour of San Francisco’s Castro neighborhood – departs from 1957, when Mike, or “Maurice” Gerry opens a hair salon on Castro Street, becoming the first openly gay business owner on the strip. Mike watched the neighborhood transform around him, as a series of migrations throughout the 1960s and 70s transformed the Castro into a gay “homeland” with a rainbow-flag stake in the ground. The tour also documents Mike’s own transformation into “Michelle,” a drag queen celebrity in the 1960s.

What surprised you as you started your research?

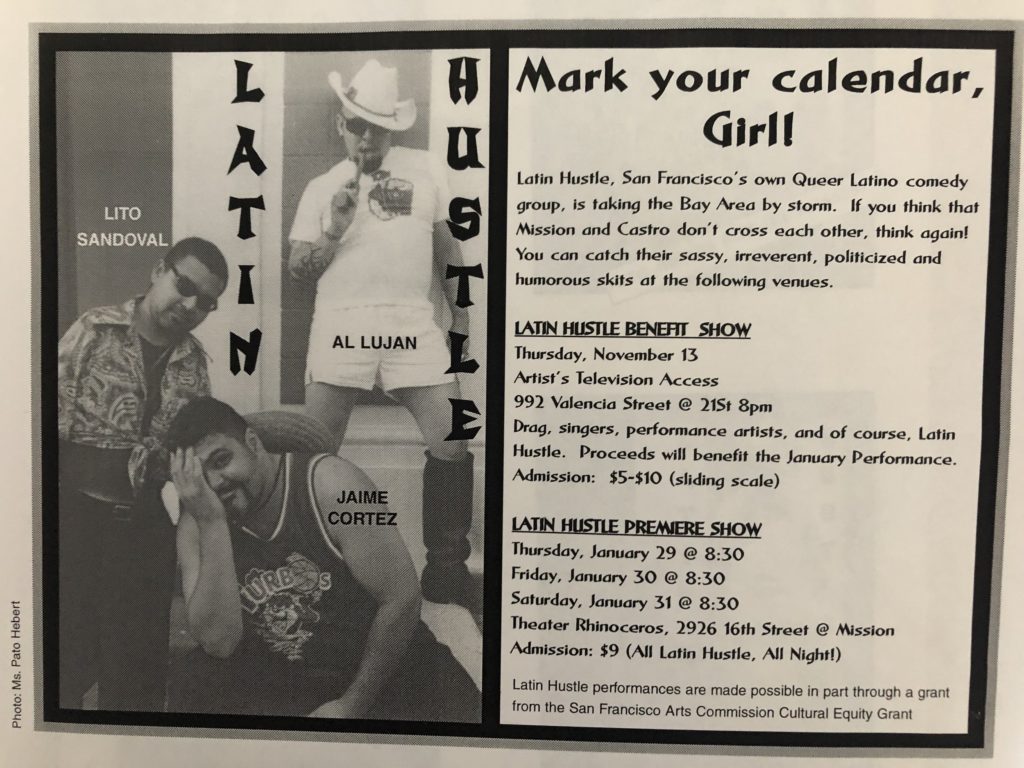

GS: What surprised me when I started digging into San Francisco’s queer history is how drag has actually always been at the forefront of the fight for LGBTQ liberation. In the 1950s, the Black Cat Cafe in North Beach became famous for its drag shows starring José Sarria. In 1961, using the Black Cat as a political headquarters, Sarria ran for San Francisco’s City Supervisor—the first known openly gay candidate anywhere in the world to run for public office. He shocked supporters by winning 6,000 votes, setting in motion the idea that a gay voting bloc could wield real power in city politics nearly two decades before Harvey Milk’s successful election.

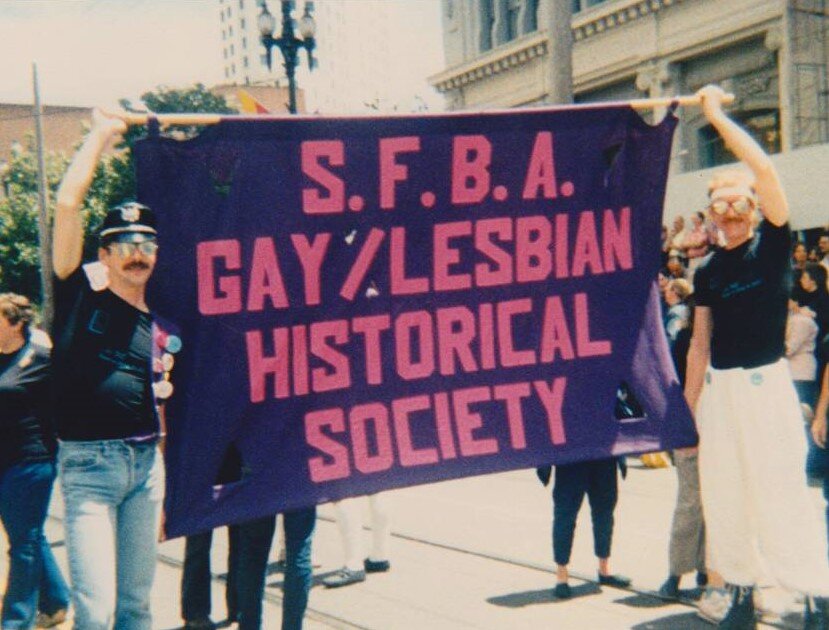

How did our archives help in your project?

GS: The GLBT Historical Society has a really awesome, extensive archival collection. My favorite is listening to oral histories, because you get to learn about the past first-hand from the people who were living it. It makes you realize there is no single story, because each interviewee experienced and interprets the events of the time differently.

One that stuck out was Craig Richmond’s interview. He was among thousands of gay men who migrated to San Francisco in the 1960s, and spoke emotionally about finding a feeling of “home” when he crossed the Golden Gate Bridge. His testimony was an important reminder that the story of the Castro wasn’t just automatic inclusion for everyone: Craig performed as a drag queen, and he said that the mustachioed men clad white T-shirts, Levi’s jeans and hiking boots (what became the classic “Castro Clone” look) were “the most narrow-minded group of people in the world.”

Why is it important to tell this story?

GS: When we first started researching our Castro tour we knew it was important to recognize how gay migration has helped shape California, but we had no idea the extent to which questions about drag were about to take center stage in US politics. In the last year there has been a drastic proliferation of anti-drag bills introduced by lawmakers across the country, restricting or banning drag shows and performers.

Today, the Castro may not be the first neighborhood in San Francisco that most people think about when they hear the word “migration.” But the LGBTQ+ migration into the Castro in the 1960s and 1970s changed the world and was as much a cry for freedom as that made by any of the other groups of “immigrants and revolutionaries” that have shaped the US.

At the start of the neighborhood’s transformation, the Castro’s new residents were predominantly white and overwhelmingly male. Effeminate men, trans men and women, or people dressed up in drag routinely faced discrimination in bars and on the streets. Queer people of color staked out their own small havens, like the Pendulum bar, but they were few and far between. Most lesbians didn’t feel welcomed.

I think that’s one thing IDHAZ (an electronic musician who narrates the tour) brings that’s really valuable. As a trans man, he finds resonances in Mike’s story: while the neighborhood is often framed as a queer Mecca, there are many ways IDHAZ feels the Castro isn’t really “for” him.

What’s next for the project?

GS: The idea is for “Migrant Footsteps” to eventually expand from San Francisco stories to a state-wide collection of California’s migration history. We have a new tour that just came out in Japantown (on Japanese Americans’ return to the city after incarceration during WWII), and another coming out in downtown Los Angeles (on Depression-era Mexican American “repatriation”) towards the end of the year. You can stay up to date on the progress and new tours coming out by signing up for our newsletter via our website calmigration.org.

How can people experience the tour?

GS: The tours are free to download! Our app, Migrant Footsteps, is on the App Store or Google Play, and it hosts a series of immersive, digital walking tours exploring migrant stories in neighborhoods across California. The idea is that migration isn’t something you can put away in a locked display case: these are living histories, often hidden in the spaces we encounter in our day-to-day lives.

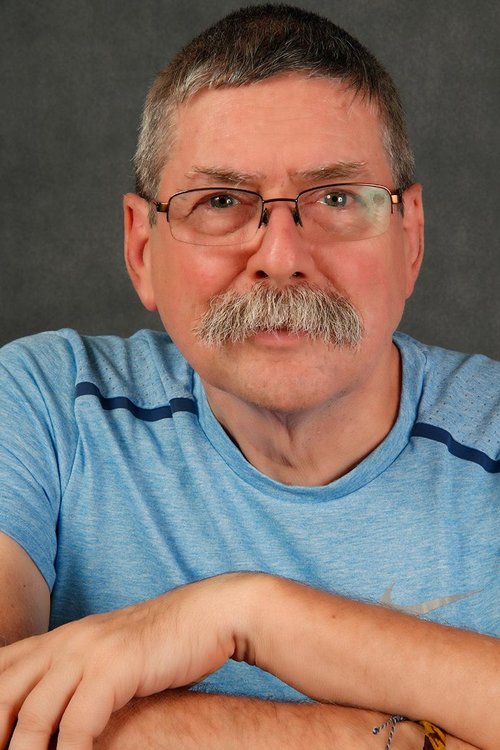

Gabby Santas is a Project Manager with the California Migration Museum. Guided by the strong belief in the power of innovative storytelling to change minds, her work with the museum brings together stories not only of arrival and welcome but also exclusion, displacement, and resistance, exploring how California was—and continues to be—profoundly shaped by migration. Gabby graduated from Brown University in 2020 with a B.A. in Socio-Cultural Anthropology. She is currently based in Berkeley, CA.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Photo Credits: The Castro Theatre on Castro Street in San Francisco, ca. 1983; Disco singer Sylvester performs at the 1980 Castro Street Fair; Women posing in San Francisco’s Castro district, ca. 1978; Two couples on the steps of a building on Castro Street in San Francisco. Sylvester photo by Robert Pruzan, Robert Pruzan Collection (1998-36), GLBT Historical Society; All others are by Crawford Wayne Barton, Crawford Wayne Barton Photographs (1993-11), GLBT Historical Society. Gabby Santas photo courtesy of same.

Jeremy Sass recently graduated from Vassar College with a BA in history and a minor in education. They researched the Vanguard queer youth organization at the GLBT Historical Society’s archives as part of their senior thesis. Since graduating, she has moved to Boston and works as a data integrity assistant at the MIT AgeLab. In their free time, they love to read, watch science fiction, and do origami.

Jeremy Sass recently graduated from Vassar College with a BA in history and a minor in education. They researched the Vanguard queer youth organization at the GLBT Historical Society’s archives as part of their senior thesis. Since graduating, she has moved to Boston and works as a data integrity assistant at the MIT AgeLab. In their free time, they love to read, watch science fiction, and do origami.