Remembering the Provocative Cult Writer Gil Cuadros

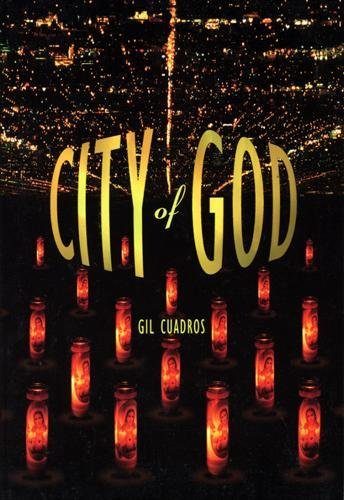

I first discovered the work of writer and poet Gil Cuadros at an exhibit on Laura Aguilar at the National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago. Aguilar is a lesbian Chicana artist known for her gorgeous photography that explores identity, the queer body, and the natural world. The exhibit featured an altar Aguilar had constructed honoring Cuadros’ life. Cuadros was a close friend of Aguilar’s until his death in 1996 from AIDS. Aguilar appears in his poem “Bordertowns” about a visit to Tijuana: Laura’s arms are crossed/to sleep, her body/ vibrates from the road. I love the way the poem concerns itself with borders literal and figurative, while also invoking a queer intimacy beyond sexuality: We hardly speak to each other/ but I turn back to see she’s there./ The vendors think we are married/ the way she snaps at me. “Bordertowns” appears in Cuadros’ book, City of God, which is split into short stories and poetry. Although it is his only full-length work, City of God remains an underrated masterpiece of gay Chicano literature.

In City of God, Cuadros fuses past, present, and future to give us his dark vision of what it’s like to be a gay Chicano man in America. Though Cuadros’ importance has been discussed by writers from Justin Torres to Sarah Schulman, he remains widely unread outside academic settings and anthologies of LGBTQ writing from the 1980s. Those who are familiar with his work love it almost to the point of obsession, or as Wanda Coleman wrote, people “accuse him of heart-bashing.” This is why Cuadros is owed a renaissance; his words are simply too beautiful to languish in obscurity. He strips language down to the bone, refusing to protect us from the truth. In doing so he gives readers a rare gift: an unfiltered window into an artist’s mind.

The brevity of Cuadros’ life, and the knowledge that he would soon die, adds a fierce urgency to City of God. He is in the company of visionaries such as David Wojnarowicz, who did not have the luxury of euphemisms or endless time.Here is a man who will not go quietly, who will not forget, who must leave a stain behind. Cuadros’ writing is infected with justified anger; he has watched numerous friends and lovers die, the world around him is apathetic to his pain, and he is haunted by ghosts everywhere he looks. City of God is his attempt to tell his story and bear witness before everything is lost.

Cuadros’ short stories are rooted in his Chicano heritage, drawing on Mexican folklore and mythology. He references Aztlan, the mythical homeland of Aztecs along with other archetypes of indigenous mythology. His writing attempts to reconcile mythology with reality and create a space for queer masculinity in Chicano culture. Reflecting this tension, his stories alternate between realistic and surreal: two young boys smearing strawberries over their naked bodies, a Chicano man acknowledging the racism of his white lover, a ghost that leaves golden coins, a young girl dealing with rape. In his poetry, the surreal is replaced by a bold and explicit physicality of expression. The defiance in these poems is their greatest strength. By refusing to shield the reader, Cuadros manages to capture truth where flowery language cannot:

I am just like any other queer,

I’ve sucked down enough come

to know that I’m infected.

The doctor thumbs my folder

looks like my father behind those glasses,

and I hold back my tears.

He runs his hands down my neck

like a lover, checking for swollen glands

and even for this he wears gloves.

In this short passage Cuadros includes so much: the failure of the body, intimacy, the pain of stigma, guilt, and self-blame, the family, and beauty even in the worst of moments. Cuadros’ work is filled with passages like these that hold space for a complex mixture of emotions.

The titular “City of God” is Los Angeles, and much like in Samuel Delany’s Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, the reader gets a rare view of a city through its queer underbelly. The final poem in City of God uses the demise of the Egyptian movie theater, a popular cruising spot, as a metaphor for the decay of the human body. Cuadros captures the excitement of meeting a stranger on the street and having sex in the bathroom of the nearly empty theater, but even in this there are hints of tragedy to come. There’s a nihilism to the poem in the limit of human experience, the futility of being “nameless creatures fucking in plain sight.” Cuadros was one of many artists at the time to note how the destruction of buildings and cultural landmarks in cities paralleled the loss of creative communities due to HIV/AIDS and displacement. “I look like the city. only bare bones of what I used to be,” he writes. In this last poem (entitled “Conquering Immortality”), he includes research on the funeral rites of the Egyptians such as embalming and mummification. These are the grim preoccupations of a man who realizes his morality is imminent. Yet through City of God, he manages to achieve a kind of immorality in his writing. Although he was unfairly robbed of a full life, as a writer Cuadros ensured that his words would survive for generations—bloody, fresh, and demanding to be heard.